The Story of Indo-European’s (Mostly) Lost Number

Reading time: 10 minutes

Introduction

One book, many books. One cat, many cats. One woman, many women. One sheep, many… well, also sheep.

In Modern English, the grammatical options for nouns are limted to two. A given noun can be singular, referring to one individual thing, or plural, which is used for any amount other than one. Of course, this includes all integers greater than one up to infinity (two houses, ten people), but the plural is also used with zero (zero trains, no trees) and with one plus a fraction (one and a half cakes). This capacity of words to change according to amount is known as grammatical number, and in many European languages, singular and plural are the only two options. However, across human languages more generally, other grammatical numbers are possible – even in the history of English itself.

One such possibility is the dual, which is the topic of the article you’re currently reading. It’s a short adventure into lost grammar, exploring the bones of a number long since devoured by its plural sister, as well as the many connections to documented languages with a living dual, both modern and historical.

As the name implies, the dual is a feature of words that conveys two of that particular thing. If you learn Modern Standard Arabic, for example, you’ll find that a noun can be singular, dual or plural.

- كتاب (kitāb) ‘book’

- كتابين (kitābayn) ‘two books’

- كتب (kutub) ‘books’

The dual in Arabic is not as strong as it once was though; in the classical language, the dual was obligatory when referring to any two things, and pronouns and associated adjectives and verbs had dedicated dual forms too.

This grammatical story of dual decline in Arabic is relevant for English, since the history of the latter language shows that English once had it too – but in English, it’s long disappeared into oblivion. Unlike Arabic, we also have no documented use of a dual number that’s hale and hearty. Even when English first enters the historical record, the dual is limited and rare. Let’s begin our journey into grammatical history with those scraps of duality.

Old English

In our sources for Old English, nouns are straightforwardly singular or plural. Relics of their lost sister number appear though in the form of personal pronouns, that is, in how Old English speakers could say ‘we two’ and ‘you two’. These pronouns sound similar to their plural counterparts; wit and ġit (pronounced ‘yit’). In the poem Beowulf, many instances of wit and ġit appear. See here how Beowulf uses wit to refer to himself competing with his childhood friend Breca:

hæfdon swurd nacod, þā wit on sund rēon

‘We had bare swords as we rowed on the sea, hard in our hands, as we two thought to defend ourselves against whales’

heard on handa, wit unc wið hronfixas

werian þōhton…

Beowulf 539-41

These two pronouns come with a paradigm of different case forms. If ‘we two’ or ‘you two’ were the object of being seen, and so needed the accusative case, unc and inc would be used, instead of nominative wit and ġit.

… nelle iċ beorges weard

‘I will not flee a footstep from the barrow’s guard, but for us two it shall happen at the wall, as fate for us decrees’

oferflēon fōtes trem, ac unc sċeal

weorðan æt wealle, swā unc wyrd ġetēoð

Beowulf 2524-6

The dual pronouns do survive past the Norman Conquest and into the Middle English period; our sources bear witness to pronouns like wit, unk, ȝit and ink as late as the 1300s, but they fade out to nothing after that century. Possible traces of a dual number might also be present in the unusual morphology of the inherently two-related words twēġen ‘two’ and bēġen ‘both’. These words show wildly different forms according to gender, with feminine/neuter twā (the origin of modern two) and masculine twēġen (the origin of twain). Compounding and analogy are responsible for elements of the unique paradigm of twēġen and bēġen, but some aspects might stem from original dual endings.

All things considered, these phantoms and fossils don’t dazzle us with the vitality of the English dual number. To appreciate its full history, we need to head up the family tree.

Germanic Languages

What we find in Old English is pretty much the situation in the Germanic family to which English belongs.

In Gothic, the oldest well-attested Germanic language, there are some dual fossils like 𐌳𐌰𐌿𐍂𐍉𐌽𐍃 (daurōns) ‘(double) gate’, but really it’s only alive in personal pronouns like 𐍅𐌹𐍄 (wit) ‘we two’. Here in the Gothic Bible, Jesus uses that very dual pronoun while talking to His heavenly father:

… 𐌴𐌹 𐍃𐌹𐌾𐌰𐌹𐌽𐌰 𐌰𐌹𐌽 𐍃𐍅𐌰𐍃𐍅𐌴 𐍅𐌹𐍄

‘So that they may be one, as we two are’

ei sijaina ain swaswe wit

Codex Argenteus, John 17.11

Likewise, in Old Norse, we find the recognisble pronouns vit ‘we two’ and it ‘you two’. The latter later becomes þit, just as its second-person plural equivalent ér becomes þér. This extra consonant they apparently gained through consistently following verbs that ended with Þ.

Having arrived on the island with sailors like Garðar Svavarsson, Old Norse was spoken and written in Iceland, where the dual would experience an unusual renaissance. While in English, the plural pronouns (we, you) ousted the dual, the opposite has happened in Icelandic. This is to say, the originally dual pronouns við and þið in Icelandic gradually usurped their plural counterparts vér and þér, becoming used for all plurality themselves.

Something similar happened on the Continent in Bavarian, spoken in Bavaria, Austria and northern Italy. In Bavarian, the cognate of Old English ġit is eß, with the accusative/dative form enk. In some dialects, eß has expanded beyond two-ness, and is the general plural form, where Standard German would use ihr.

However, as in English in particular, all this shows that the Germanic dual is a shadow of its prehistoric glory. To get a sense of that status, we should turn to Germanic’s ancient relatives.

To Antiquity and Beyond

If we broaden our scope to English’s distant cousins many-times-removed, such as Ancient Greek, Sanskrit and Avestan, the dual is a fully functional grammatical number. We find it not only with pronouns (e.g. Ancient Greek νώ (nṓ) ‘we two’), but nouns, adjectives and verbs can also be dual in form and meaning.

च॒क्र॒वा॒केव॒ प्रति॒ वस्तो॑रुस्रा॒र्वाञ्चा॑ यातं र॒थ्ये॑व शक्रा

‘Like a pair of Cakravāka-birds, come here at daybreak, like two charriot drivers, you two mighty ones’

cakravākā́ iva práti vástor usrā / arvā́ñcā yātam rathyā̀ iva śakrā

Rigveda 2.39.3

In Ancient Greek, the dual number and its endings are unsurprisingly common with things that come in natural pairs. This is noticeable with certain body parts, like hands or eyes.

τὸν δὲ σκότος ὄσσε κάλυψε

‘And darkness covered his eyes’

tòn dè skótos ósse kálupse

Iliad 4.461

However, even in these ancient languages, the dual is a sickly part of grammar. It limped on into later Classical Greek, maintained in natural pairs and stock phrases, but no further into the Hellenistic period. Over the Adriatic Sea in Latin, it’s almost nowhere to be found; it survives in the unusual declension of the naturally dualistic words duo ‘two’ and ambō ‘both’. Moreover, it did not survive past the ancient period of Sanskrit into the spoken vernaculars of Middle Indo-Aryan. It is also surprisingly absent from the oldest documented branch of the family, Anatolian, with only traces in Hittite.

There are again only whispers of duality in early Celtic languages like Gaulish, Old Irish and Old Welsh, in particular in the form of the number ‘two’. Old Irish has certain duals like láim ‘two hands’ and súil ‘two eyes’, which must be accompanied by the number two. These are body parts and natural pairs, but Old Irish also exhibits dual forms like mnaí ‘two women’, which is not determined by nature. This hints at a certain vitality to the dual in old Celtic languages, and it’s worth noting that relics have endured into the modern-day languages. To say ‘my two hands’ in Scottish Gaelic is mo dhà làimh.*

All in all, the picture that this comparative evidence paints is that the dual must have been a part of the grammar of Proto-Indo-European itself, alongside the singular and the plural. We’re even able to reconstruct some of the original endings for dual nouns. ‘Two sheep’ for instance would have been *h₂ówih₁e, and ‘two fields’ would have been *h₂éǵroh₁. The ancestral language must have used it when talking about pairs of things; it may have even been obligatory to do so.

However, what we also observe is the parallel loss of the dual across the various branches of the Indo-European family tree. Over and over, we find that the plural comes to be used instead for indicating two things, relegating the dual to pronouns and idioms. Given this pattern of change, the roots of the rot may lie in Proto-Indo-European itself, or in an inherent redunancy of the grammatical number. If the plural can be used to count between three and infinity, it’s no great stretch to extend that use to one more number, namely two.

For sure, the general story of the dual number in Indo-European is one of decline – but not of definitive defeat!

Dual Death?

‘But!‘ I hear the keener linguists among you cry. It’s true, the dual ain’t dead in Indo-European! There are languages in the family that have maintained the dual to a greater or lesser extent, either in obvious fossilised morphology or as a full-blown feature of grammar.

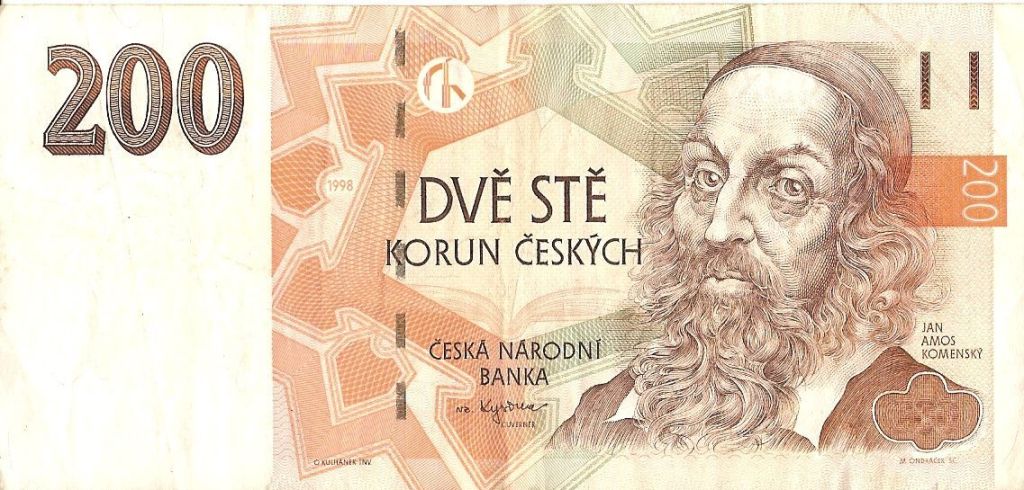

Lithuanian and the Slavic languages have offered a refuge for the embattled number. In some regions of Slavic, such as Czech, the dual survives in the unexpected endings of natural pairs. One eye and one hand are oko and ruka, while two or more eyes and hands are not regular oka and ruky, but the old duals oči and ruce. Likewise, the Czech word for ‘hundred’ (sto) has a form used especially in ‘two hundred’ (dvě stě).

What’s more, Slovenian (spoken in Slovenia) and Sorbian (spoken in Germany) continue to use the dual as a productive feature of the grammar. This extends beyond natural pairs to any two things, as in the Slovenian for ‘house’:

- hiša ‘house’

- hiši ‘two houses’

- hiše ‘houses’

However, it’s reported that even here the dual is retreating to natural and typical pairs, and is:

“… also becoming unstable in dialectal and colloquial use. It is likely to remain operational in the standard languages by virtue of being enshrined in the authoritative prescriptive grammars of these languages … the dual has been saved in Slovenian through the ‘intervention of grammarians’.”

Sussex & Cubberley 2006: 225-6

Even in these dens of duality, there seems to be an element of the artificial to the number’s continued usage.

So, this has been a quick tour through a ghost of English grammar, a forgotten sister of the dominant singular and plural. If anything, I hope it serves as an interesting example of family-wide language change, and of how we can’t take the features of our modern grammar as given. Other grammatical possibilities exist, and may even haunt our very own languages!

END

References

- Blanc, H. (1970). Dual and Pseudo-Dual in the Arabic Dialects. Language, 46(1), 42–57.

- Hoffner, H. A., & Melchert, H. C. (2008). A Grammar of the Hittite Language. Part 1, Reference grammar. Eisenbrauns.

- Hogg, R. M., & Fulk, R. D. (2011). Grammar of Old English: Volume II: Morphology. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Majewski, K. (2022). The Ruthwell Cross and Its Texts: A New Reconstruction and an Edition of The Ruthwell Crucifixion Poem (Vol. 132). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Ringe, D. A. (2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. A Linguistic History of English (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

- Sihler, A. L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Sussex, R., & Cubberley, P. (2006). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge University Press.

- Thurneysen, R. (1975). A Grammar of Old Irish. Translated by D. A. Binchy & Osborn Bergin. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Wiesinger, P. (2013). The central and southern Bavarian dialects in Bavaria and Austria. The Dialects of Modern German. 438-519. Routledge.

* With my thanks to Caoimhín Ó Donnaíle for the helpful tips about Scottish Gaelic.

Cover picture from here.

I read (in a pop-linguistics book, don’t know any real historical sources) that the Dutch place-name Leiden comes from a dual form Leython, “on the two streams”. (That’s the sort of thing that sticks in my brain because dual is cool)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read somewhere that the dual kinda lives on in English in the form of “both” – i.e. we make a three-way distinction “only I should go” (singular), “both of us should go” (dual) and “all three/all four/all five etc. of us should go”

LikeLiked by 1 person

as well as “whether” and “either”

LikeLike

That’s an interesting article. I understand that the very odd behaviour of enumerated nouns in Slavonic languages is another relic of the dual, which (as you say) survives in literary Slovene and to a lesser degree in some Croatian dialects. So in Croatian the numbers two to four are followed by the noun in the genitive singular (to which the dual form assimilated) but five and above by the genitive plural, e. g. cetiri zene (four women) but pet zena (five women: what’s more, not only does the ending change but the stress falls heavily on the first vowel of the plural form, which is lengthened).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting, as always.

Out of interest the dual survived into early Middle Welsh,its peculiarity being that it caused a soft mutation to a following adjective. Forexample n the Second Branch of the Mabinogi (12c) we have a reference to two trouserless(bonllwm) Irish throwing Efnysien into the Cauldron of Rebirth hence âdauWyddel fonllwmâ, in ModW orthography (b > v). Thereâs also thestriking coastal massif composed of three striking peaks called Yr Eifl, from gaflâforkâ. Geifl is the dual, and as with the adjective above the nounlenites after the definitive article, hence gafl > yr eifl (thetwo forks). Another survival of this in ModW is that the masculine form for âtwoâalso lenites after the definite article, hence dau > y ddau.Itâs productive in modern Breton, but only really after parts of the body,most of which are for obvious reasons in pairs. However, as not all consonantsare lenitable and that this would occur, as in Welsh, after a dual noun, itâs veryinfrequently encountered. During a year and a half speaking only the Leon dialectin the NW I only ever heard it once, in the phrase âtwo blue eyesâ â daoulagadvleu (< bleu).

Thanks again for a great post. This will be shared on Iaithand Iâm confident this will attract many readers.

Dr Guto RhysBrwsel/Brussel/Bruxelles/Bruselas

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love the title. I can see why the dual form would eventually give way to the plural. It makes me wonder why a separate dual form ever came about in the first place…

LikeLiked by 1 person