Reading time: 5 minutes

(With my apologies to subscribers for the second email, following an accidental premature publication)

I’m very keen to share a fun linguistic adventure that I found myself on this week, as I dug down into the history of the humble English word street.

It all began with a Patreon post by the etymologist extraordinaire Yoïn van Spijk about the oldest layer of Latin loanwords in English. While the majority of our Latinate vocabulary entered English after 1066, there is a fascinating small set of words whose borrowing predates that by several centuries. Heck, it predates any birthday we could give for English as a distinct language. These are words that were adopted from Latin while English was only a West Germanic dialect, spoken on the Continent. One member of that set is street.

As Yoïn notes, street goes back to Latin strātus, a participle meaning ‘spread, covered’, or for roads specifically ‘paved’. Having passed into the Germanic languages, in time it also gave rise to Dutch straat and German Straße.

The diagram reminded me of an exciting additional detail in the history of street, something I must’ve picked up from a reference book like Mills’s Dictionary of British Place-Names. It’s a semantic point, namely that the word street seems to have maintained its association with the Romans long after its adoption into pre-English and its arrival in Britain.

In our textual sources, the Old English word strǣt clearly means ‘street’. This is to say, it has a generic meaning of a road, typically one between buildings within a settlement. In contrast to earthen tracks, a strǣt was probably paved.

“Strǣt wæs stānfāh“

‘The street was stone-paved’

Beowulf 320

Texts aren’t our only witnesses to Old English though; the place names of Britain are a treasure trove of linguistic antiquities, many going back to the very early post-Roman period, when the Germanic-speaking Angles and Saxons were establishing themselves in Britain. In those names, we find evidence for an older meaning of strǣt.

It’s said that strǣt once meant specifically ‘Roman road’. To be more precise, it referred to a road in the Roman style, because it came from the Latin word for ‘paved’, and the old Roman roads across Britain were the ones that were paved. As part of their conquest from the first century AD onwards, the Romans built their network of (fairly) straight roads according to a template; this included solid foundations, ditches and paving on top.

Compared to the paths that the Angles and Saxons were forging themselves, Roman roads were probably still superior, and must have remained a distinct and impressive presence in the British landscape. So, in earlier Old English, a strǣt was exclusively Roman. As time went by though, and the new inhabitants started paving their own roads, I imagine strǣt became broader in its use.

What evidence though can place names offer for this Roman-associated meaning of strǣt? The traditional wisdom goes that names for English places that include strǣt in their name sit on old Roman roads. The idea goes that the post-Roman, English-speaking settlement was either built around or at least characterised by the Roman road that ran through it.

Some of the examples I was familiar with already: Stratford in Greater London sits on the route between London (Londinium to the Romans) and Colchester (Camulodunum), while Stretford lies between Chester (Deva) and Manchester (Mamucium). Note the common chester element, from Latin castra, another toponymic ghost of Rome. But how common really is this rule that strǣt-names are found on old Roman roads?

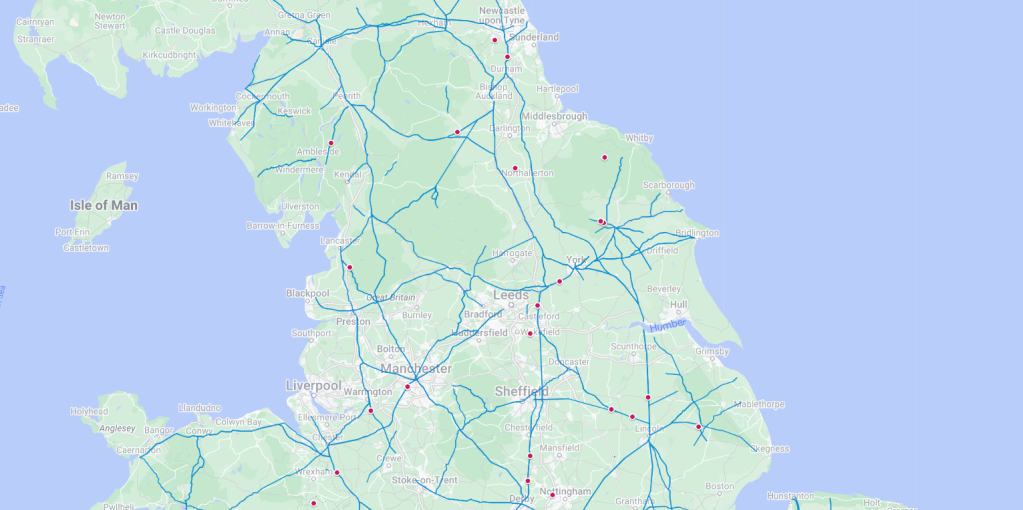

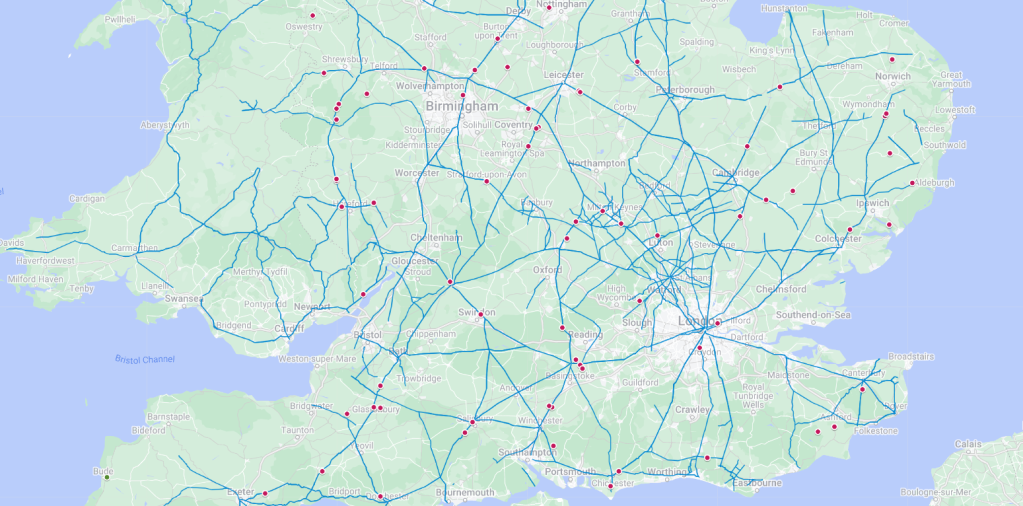

Relishing the chance to research and plot some cartographic data, I set out to map them. My first step was to download a map of Roman routes, available here, on which the roads are drawn primarily according to Codrington’s Roman roads in Britain (1918). Codrington’s information comes from three complementary sources: (1) archaeological and geographical evidence in the landscape, (2) itineraries made by the Romans themselves, and (3) toponymy, the evidence from place names. With this basis, and with many helpful examples from people on Twitter, I plotted every strǣt-name I could find, from Stony Stratford and Church Stretton to Great Sturton and Chester-le-Street.

The picture that quickly emerged is that this association seems to be very strong, intoxicatingly so. With each addition to the map, I found that these villages are consistently located on where we know or suppose an Roman road once ran. See for yourself!

I’ve made the map publicly available here, to share the toponymic joy further. There are exceptions to the rule, of course, but several can explained as consequences of village drift, or as a name adopted from elsewhere. For other examples, recent archaeology, Lidar and the name itself can make a case for a Roman road not widely recognised.

Now, some people have raised fair points about the significance of all this coincidence, whether or not the picture is misleading. Perhaps there is no association, because all post-Roman settlements developed along Roman roads? These are weighty issues of causality that the expert historian’s brain is used to working with. My amateur’s understanding at least (gleaned from magnificent works like Fleming’s Britain After Rome) is that while the old roads were still important and used, they did not constrain the settlements of the incoming English. There would’ve been many more routes besides those put down by Rome, and it was good land first that determined where people set up home, good roads second. For me, this all seems like pretty solid evidence for the idea that streets were originally Roman.

The strǣt-names also seem to attest to a dialectal divide within Old English, namely between West Saxon and Anglian vowels. Names with E (Stretton, Stretham, Stretford) seem to belong to the North and Midlands, while names with A (Stratton, Stratford) appear more southern overall. This we expect, since they reflect the difference between Anglian strēt and West Saxon strǣt.

I’ve also noted that the strǣt-names tail off towards the north, and I haven’t found any beyond Hadrian’s Wall and into Scotland. We know that Old English speakers settled on both sides, so can this absence be taken to mean that they didn’t find any nice, strǣt-worthy roads north of the wall? Before I enrage historians any further with my speculations and conclusions though, I should stop here.

So, that’s just what I’ve been obsessive about this week. I hope you, dear reader, get a small sense of why.

END.

References

- Codrington, T. (1918). Roman roads in Britain. Sheldon Press.

- Fleming, R. (2011). Britain after Rome: the Fall and Rise, 400-1070. Penguin.

- Mills, D. (Ed.). (2011). A Dictionary of British Place-names. Oxford University Press.