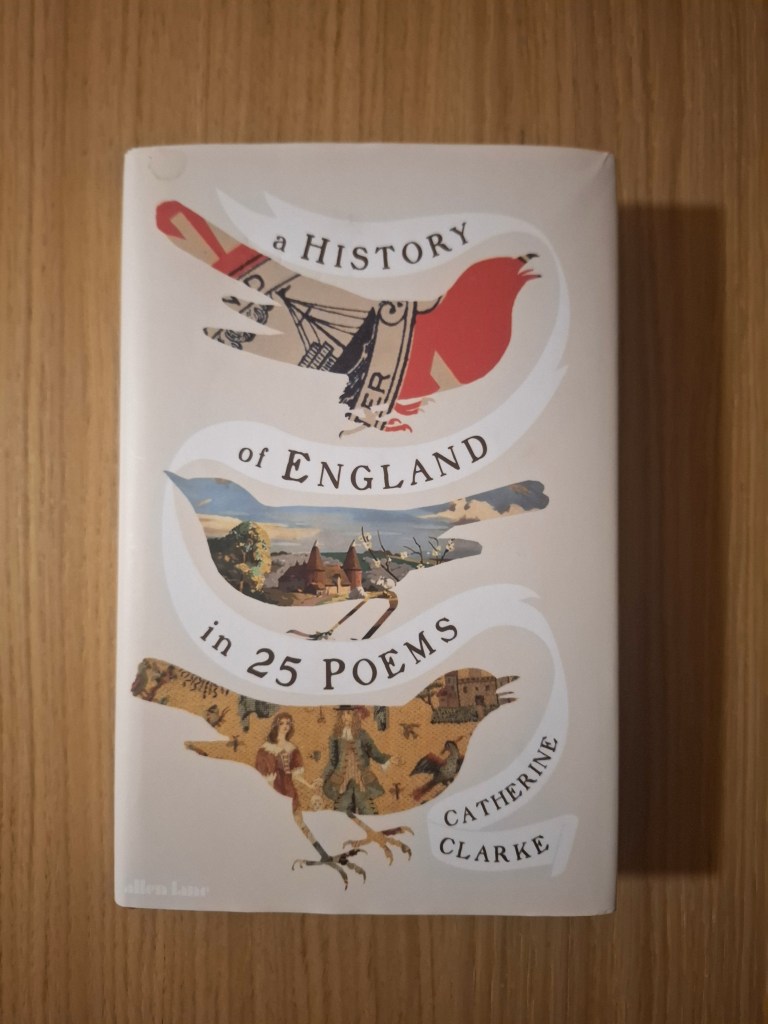

In September this year, Catherine Clarke, professor at the Institute of Historical Research, published A History of England in 25 Poems. This chronological hike through England’s history via verses that its people have left behind was released to great acclaim – and no wonder, when the book manages to be comfortable and accessible, yet also profound and innovative. A scholar’s insights into poetry are deftly structured into twenty-five strictly short chapters, each as long and pleasant as a nice cup of tea. When such a book is so taken to heart by the British book-reading public, it makes me hopeful for non-fiction in general.

Now, when it comes to any sample of language, I think as a linguist first, as a historian second, and maybe fifth or sixth as a wannabe poet. The primary module of my brain was activated while reading Chapter 5 and its starring verse, the lyrics of the thirteenth-century song Sumer is icumen in. Its language is English, or rather the ancestral Middle English, and its subject matter is very light; its chapter in Clarke’s book explores both the text and the context of this “poem about farting farmyard antics”.

sumer is icumen in

Summer has arrived,

lhude sing cuccu

groweþ sed

and bloweþ med

and springþ þe wde nu

sing cuccu

awe bleteþ after lomb

lhouþ after calue cu

bulluc sterteþ

bucke uerteþ

murie sing cuccu

cuccu cuccu

wel singes þu cuccu

ne swik þu nauer nu

sing cuccu nu sing cuccu

sing cuccu sing cuccu nu

Loudly sing, cuckoo!

The seed is growing

And the meadow is blooming,

And the wood springs [into leaf] now.

Sing, cuckoo!

The ewe bleats after her lamb,

The cow lows after her calf;

The bullock prances,

The billy-goat farts,

Merrily sing, cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo,

You sing well, cuckoo,

Never stop now.

Sing, cuckoo, now; sing, cuckoo;

Sing, cuckoo; sing, cuckoo, now!

A reader’s first impressions and questions provoked by this cacophony of Middle English will sift out the historical linguists from the rest. The musician may wonder how these rambunctious lyrics were performed; the historian may wonder why they were written down and preserved until today. These questions came late to my mind; naturally, it was preoccupied by the H in “lhude” and “lhouþ“.

Now I’ve brought your attention to it, you may also admit to wondering what H is doing there. The words that contain it are translated by H-less Modern English descendants: loudly and lows. The wondering may be compounded by the fair assumption that every letter in medieval texts serves a purpose; in a time when ink and parchment were labour-demanding materials, idle letters were grievous wastage. That is to say, the H was not a silent bonus letter, like the H in hour or B in doubt; it had to contribute something to the encoding of speech.

The nerd that I am, I was already aware of this feature of Middle English. But, like a rare bird for the off-guard ornithologist, it was nice to come across it in the wild. So, what does the H offer the words lhude and lhouþ? These two words belong to a wider pattern of spelling, utilised to spell sounds long since swallowed by the mouths of English speakers.

To understand this H, I will transport your thoughts to the linguistic era that preceded Middle English and the language of Sumer is icumen in. That era was the Old English period. In this pre-Norman tongue, the ancestors of the two words under examination are hlūd and hlōwan. Their H had therefore been there for centuries before the song, but it used to precede the L. Curiouser and curiouser.

An H appears at the start of more Old English words whose present-day descendants lack it. In the HL club, we also find hlēapan, hlot and hlāf – today, leap, lot and loaf. We have hrōf, hring and hrēaw for today’s roof, ring and raw. Old English speakers knew the humble nut as a hnutu, and the neck as a hnecca.

The comparative evidence – harvested from English’s wider Indo-European family tree – leads us to believe that the HL, HR and HR in these old words were once pronounced as a sequence of two sounds. Spelling them with two letters was therefore a reasonable practice.

At an earlier stage, the H likely represented a /x/ sound, as heard in a Scottish loch or a German Buch. This fricative was a product of a serial sound change in the prehistory of English, known as Grimm’s law. English’s unaffected relatives, such as Latin, maintained the pre-Grimm /k/ consonant. Hlūd and hlōwan have Roman cousins in Latin cluēre ‘to be called’ and clāmāre ‘to shout’.

However, as documents in Old English gradually become middle-aged, we find examples of these words without the initial H. Such spelling ‘mistakes’ are indicators, gratefully received by historical linguists, that the sound behind the H was starting to be dropped from the spoken word. This view is propped up by poetry, which wordsmiths constructed at the time through alliteration, making the initial sounds of words match. If the composer of the poem Judith (c. 1000) could alliterate “rēocende hrǣw” (‘reeking corpses’), it suggests that their speech lacked, or at least could lack, an audible sound for the H of hrǣw that would block the poetic pattern.

Yet the H did not go quietly. It fused with the sound of the following L, N or R, or rather donated a phonetic feature to it. It thereby created a trio of new consonants for spoken Old English. These were much like regular L, N and R, except that they were voiceless; they were pronounced without vibration in the larynx. This quality was a legacy of the voiceless H sound. It’s hard to convey in text the subtle difference between regular L, N and R and their unvoiced versions, but a comparable difference exists still over the border from England; Welsh speech distinguishes between sounds spelled L/R/N and those spelled LL/RH/NH.

It is one such voiceless sound that our songster had in mind and mouth two centuries later, when they wrote lhude and lhouþ in Sumer is icumen in. The H was not a relic or a taught rule from Old English writing; the tradition of spelling practices from that time had been severed by the events of 1066. Instead, the LH here reflects a sound still distinct enough from L to deserve its own spelling.

The reversal of the two letters reflects the change to the original sequence of sounds; Middle English authors heaped a heavy burden on H, using it to create pairs of letters (digraphs) that could spell sounds beyond what singleton letters could manage. Some digraphs still in use today (e.g. CH, GH, SH) date to this era of English. Alongside LH, we find RH and NH sporadically in Middle English texts. They consistently appear in words derived from Old English ancestors with HL, HR and HN, demonstrating that this was not memory, but an active difference in speech.

This situation, as you can hear for yourself, was not to last. However much you use the archaic verb low today (depends, I suppose, on how much time you spend around cows), the L at the start of low and also loud now sounds the same as an initial L anywhere else. Likewise, roof, ring, nut and neck have the usual voiced Rs and Ns. This is because the pairs of counterparts, one voiced, the other voiceless, went on to merge in speech. They merged in favour of the more common voiced versions.

When that merger happened, however, is not at all straightforward. Scholars adduce spellings and poetry as evidence that it had already begun in the Old English period. Whether this is correct, the instances of LH, RH and NH in Middle English indicate that it was yet to happen or ongoing for some post-1066 speakers.

For example, from 1258, we have a proclamation of Henry III, named “king on Engleneloande, Lhoauerd on Yrloande”. The spelling of lord here (etymologically a ‘bread-guard’) harkens back to Old English hlāf. Presumably, this records a southern dialect of Middle English, written in England’s political heartland.

Further north, in Lincolnshire, the delightful Orrm spelled the same word as “laferrd”. The two writers differed not only in geography but also chronology; Orrm was composing Middle English in c. 1180, well before Henry’s proclamation. He does, however, spell roof as “rhof”

& tanne toc þe deofell himm

And then took the Devil Him

inntill þatt hallȝhe chesstre

þatt iss ȝehatenn Ȝerrsalæm,

& brohhte himm o þe temmple,

& sette himm heȝhe uppo þe rhof

Into that holy city

That is called Jerusalem,

And brought Him onto the Temple,

And set Him high upon the roof

(Ormulum 11347–11351)

For Lincolnshire language, we can take laferrd and rhof as evidence that the two types of L had merged by that time, but not so with voiced and voiceless R.

Whatever trends towards the ultimate merger we detect, an outlier is the Ayenbite of Inwyt, a curious religious text from Canterbury in 1340. Its translator and composer, the monk Dan Michel of Northgate, consistently uses the conservative LH in “lhord” and “lheste” (lord and listen), as well as NH in “nhote” (nut).

þeruore zayþ oure lhord þet þe kingdom of heuene is hare

Therefore says our Lord that the kingdom of heaven is here

(Ayenbite of Inwyt: The Seventh Bow of Mildness)

The possibility remains that this was poetic affectation, a means to make the language sound archaic and venerable. Yet I fail to see how Dan Michel would have thought that about LH and NH, nor how it would have benefited his work. Instead, it’s simpler to see this as a faithful rendition of Kentish English in the fourteenth century, which still had LH and NH as separate in sound from L and N. If he had travelled to innovative northern regions, Dan Michel’s accent might well have sounded alien and strange, possibly old-fashioned. It would be Caxton’s eggs all over again. In poking our noses into lhude and lhouþ, we gain an appreciation of the depth of diversity across medieval England.

Ultimately, though, Modern English pronunciation owes more to Lincolnshire than to Kent, as it was from the East Midlands that standard speech began to emerge. The doom of the voiceless consonants inherited from Old English was certain: to be lost from the relevant dialects of Middle English before LH, RH and NH could make their mark on our standard spelling. They belong now to the dustbin of writing and speech, whispers of Englishes past.

With one exception.

There is a survivor in this group of consonants, artfully unmentioned so far. Circling back to Old English, we find that initial H not only before L, R and N, but also W.

Words with HW (more commonly written HǷ, with the lost letter wynn) include hwæt, hwæl, hwǣte and hwīt – today, what, whale, wheat and white. These noticeably contain an H. While an H in a word like lord or nut might offend our modern eyes with excessive antiquity, it feels perfectly normal in while, whether and when.

The same process that happened with HL, HR and HN happened with HW. However, the voiceless sound that the fusion of HW created lasted for much longer. It can still be heard today. There are flavours of English speech that still keep whether and weather distinct in their first sound. The former begins with a voiceless /ʍ/; the latter with the more common /w/.

These accents, still to be heard in Scotland, Ireland and the USA, are fighting the ongoing ‘wine–whine merger’. My own accent succumbed long before I was born, but to keep wine separate from whine was typical talk in southern England up to the eighteenth century.

The slow conquest of the wine–whine merger is a present-day chapter in the story of sounds that began life back in Old English times. The loss of the voiceless LH, RH and NH sounds may be a done deal across English speech, but their embattled comrade, WH, connects us to their era.

When we gain our speech, we inherit not simply stable sounds, but a living, changing system. Those inbuilt changes are linked in a chain of causality that, I suppose, began with the first meaningful grunts. For me, reflecting on the wine–whine merger breathes life back into the language of a historical artefact like Sumer is icumen in, making the language of thirteenth-century folk feel familiar, tangibly like my own.

END.

English spelling and many of the topics mentioned in this piece are discussed in detail in my own book, Why Q Needs U, recently reviewed by The Economist, described as “charming” and “a biography of the English language and an introduction to linguistic science, all smuggled into short, lively and entertaining stories”.

References and resources

- Matyushina, I. (2018). On The Diachronic Analysis of Old English Metre. International Journal of Languages and Linguistics, 5(3), 260-270.

- Upward, C., & Davidson, G. (2011). The History of English Spelling. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ayenbite of Inwyt text

- Middle English Compendium

- oed.com

- The Ormulum text

- The Proclamation of Henry III text

Original Substack post. Images my own or from Wikimedia.

Bonus grammar fact:

‘Sumer is icumen in’ is in fact perfective in its tense and aspect; summer is already here. We would properly translate it today as ‘summer has arrived‘. The clause is a relic of a time when English used be as an auxiliary verb that built the perfect tense with verbs of motion, just as French and German still do. English at that time also had a prefix to add to past participles (the i- of icumen), which German again maintains (the ge- of gekommen).

The voiceless /ʍ/ which some varieties of English preserve for initial wh- is in England also a feature of not only social dialect (‘upper class English’) but also ‘BBC English’ (or whatever you care to call either).

LikeLike