Some personal news from me:

My first peer-reviewed academic article has now been published with the Journal of Historical Syntax! After almost a year of work by me, three reviewers and the editors of JHS, Deriving the Old Irish Clause now exists out there to be read and hopefully enjoyed. It can be found here and is publicly available, as per the principles of the journal.

About the Article

To summarise the paper, it’s my analysis of the infamous intricacies of the word order of Old Irish clauses, within the framework of modern generative grammar. It surveys the linguistic evidence of five broad types of clause in this historical language, with the ultimate goal of proposing a single abstract syntactic structure that Old Irish speakers may have had for their language, and that would ‘generate’ good grammatical sentences in Old Irish.

It emerged from my research for a chapter of my PhD thesis, Old Irish being one of the seven languages that I have undertaken to analyse and compare, in order to reconstruct something of the syntax of their common ancestor. As such, it’s built from two very separate fields, namely modern formal syntax and the well-established philological tradition of historical Celtic languages. Like its author, it’s therefore a linguistic Frankenstein’s monster, but one that I hope might be useful for someone somewhere.

It begins by introducing Old Irish and some of the (brilliant) historical sources we have for it, as well as the way I think about and approach syntax. It then turns to the key features of the way Old Irish assembled its words into clauses, in particular the fascinating ‘verbal complex’ that usually comes first. Having caught the reader up on the delights of the data, from prototonic verbs to infixed pronouns, it sets out my new proposal for how an Old Irish speaker produced or ‘derived’ a clause – first through the building of syntactic structure, then through the computation of phonological rules. This account I then apply to other types of clause: relative clauses, adverbial clauses, complement clauses, interrogative clauses for questions, and imperative clauses for orders (my favourite type). After considering some interesting outliers to the usual VSO word order, it then concludes and lists a whole load of more talented scholars’ work.

Apologia

I expect and have received some push-back from philologists in response to this kind of work, and what my historical-linguistic comrades and I seek to do. It’s very fair that Old Irish scholars should ask what new contribution the article makes to their knowledge of the language, and wonder so what? In truth, it doesn’t offer any new philological insights. It is first and foremost an article by a historical syntactician for other historical syntacticians, although I hope the introductory explanations if nothing else offer an intellectual olive branch to other disciplines.

This gets to the heart of the difference between philology and historical linguistics, two fields that have so much in common, yet differ fundamentally in motivations and goals. Being at heart a historical linguist, I am interested most in ‘Language’ and the complex systems that produce this human behaviour. Consequently, while I love any ancient text for what it is, my primary research interest is in the linguistic capabilities of its author – in putting historical language back into the brains of its producers. Generative grammar is one syntactic school of thought that allows me to do just that. While philology concerns itself with the what of a language, I’ll always want to dig into the how and the why, but I in no way consider either to be the superior academic endeavour.

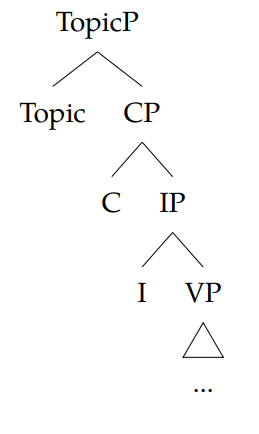

Being one of, if not the dominant camp in the field of syntax today, I believe that this article would have been worthwhile work if only to combine field and language, to see how well or not generative grammar can deal with Old Irish. I should say, it’s also not the first attempt to do so! Overall, I dare say it works very well; my conclusion is that the features of the Old Irish clause, despite their fierce reputation, could have been produced by a pretty simple general syntax. In accordance with the customs and concepts of the generative framework, I model it like this:

The complexities instead arise from the specific bits of vocabulary that instantiate these different syntactic components across the different types of clause. An analytical tool like “C” is moreover able to consolidate and account for a variety of word-order behaviours, including Old Irish’s beloved deuterotonic verbs and infixed pronouns.

I reckon the article also opens up tantalising avenues for further research, especially in connecting the syntax proposed for Old Irish to later stages of the Irish language, and to the Indo-European family more widely. One such article is currently in production, which offers a reason for why, in a piece about Old Irish, Sanskrit gets mentioned so much…

Hi Danny,

<

div>Congratulations

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Guto, thanks for the comment and the congrats. Unfortunately, that’s all I can see of the comment! Is that everything or is there more beyond the congrats? Danny

LikeLike