Reading time: 10-15 minutes

To listen along in an audio format, just click here:

IT’S WELL KNOWN that English has undergone many significant changes down the centuries. Events like the Norman Conquest have drastically altered the shape of the language, influencing words and sounds so much that a new kind of English was born. Yet language doesn’t need political upheavals to change; it’s in the nature of language to differ across time, although we don’t notice many of these divergences while we are living through them. Consequently, we can describe certain aspects of English as innovative, meaning they are relatively recent, in comparison with other aspects. For this post though, I want to concentrate on those features of Modern English that, despite all these historical changes, are conservative – that is to say, really old.

There’s no start date for when the English language ‘began’. It’s rare for any language to have such a beginning, since most natural languages are transmitted over time from one generation to the next, without any clear breaks in that transmission. It’s typical and convenient to place the birth of English after it first reached the island of Great Britain in the 5th century AD and the slow formation of England began, but to begin with, that language would have been indistinguishable from what its speakers left behind on the Continent.

What we do have though is a linguistic timeline of the transmission of English, stretching back through prehistoric stages of language, each one with a pretty longwinded name. English goes back to Proto-West-Germanic, and then to Proto-Germanic, and millennia before that to Proto-Indo-European itself. Because we have a good idea of what these proto-languages were like, we can see how certain features of English today go all the way back to those ancient days. In some cases, these are features that have meanwhile been lost in English’s many linguistic cousins.

So, allow me to show you in five examples how English can be ancient! There’s plenty of good information out there about how certain words in English are of prehistoric pedigree (e.g. mother, father, daughter, son), so I’ve chosen to concentrate instead on smaller features that are no less interesting: four bits of grammar, and one wonderful sound.

1: I Am What I Am

If we take a broad view of the Indo-European language family, a common feature is that the first person singular (that is, I) can be expressed through the sound /m/. What I mean to say is that we often find -m or -mi added to the end of verbs to signal that I did the action in question. Here’s a sample:

- Latin: amābam ‘I was loving’

- Ancient Greek: dídōmi ‘I give’

- Sanskrit: paśyāmi ‘I see’

- Irish: gabhaim ‘I take’

- Slovene: hočem ‘I want’

- Persian: mi-konam ‘I do’

On this basis, it’s believed that Proto-Indo-European expressed the first person singular through the endings *-mi and *-m. However, as is typical, how well these endings survived differed from language to language. In English today, we have a single direct trace of that ancient affix: I am.

2: Vowel Swapping

My fourth ancient artifact is a key bit of grammar in English today, concerning verbs and their vowels. English verbs roughly fall into two camps: weak (play, dance, compute) and strong (eat, drink, sing). The difference is how you put these verbs into the past tense. For the strong group, what we do is alternate the vowel (ate, drank, swam). This phenomenon is called ablaut, something I’ve introduced and discussed in detail before.

The thing about ablaut is that it’s old. Really old. Granted, the specific vowels involved have changed many times over the history of English, but as a system, the vowel swapping in verbs like swim–swam–swum or write–wrote–written goes back all the way to Proto-Indo-European. We can claim this because it appears across the Indo-European languages, although it varies in vitality. In Sanskrit, for instance, ablaut is thriving, used to express a variety of verbal information. Just compare

- bodhati ‘she wakes (someone)’

- gopayati ‘she protects’

with

- budhyate ‘she is woken’

- gupyate ‘she is protected’

In Ancient Greek, it’s likewise a frequent feature of verbs and other categories of word, yet in Latin the system has really been reduced to relics and residue, seen in related words like the verb tegere ‘to cover, clothe’ and the very Roman noun toga. Similarly, in Slavic languages like Czech, the ghost of ablaut only lingers on in vowels that appear or disappear between different forms of a few verbs, such as between beru ‘I take’ and brát ‘to take’.

The origins and original purpose of this phenomenon are unclear and debated, but it was clearly a lively feature of English’s prehistoric ancestor. While strong verbs may today be the weaker pattern, they still retain that liveliness. So, when you say you ate, drank, rode, sang, flew or ran, you’re tapping into millennia of grammar.

3: Who’s What and What’s Who?

English has a set of words that are used to form questions, and to specify the kind of information that is being sought. We call these wh-words, and they include who, what, when, how and where. Each has its own function; when asks for information about time, where about location. But what’s the difference between who and what? The two don’t seem to differ as much in their function, since they both seek information about a specific thing. Instead, the difference is the type of the unknown thing. We use who for people, as well as animals that are familiar and person-like in our eyes. We use what for everything else.

Similar divisions between human who and generic what is something that we find across the Indo-European family – compare German wer and was, Latin quis and quid, Ancient Greek tís and tí, Old Church Slavonic kъto and čьto, Persian ki and če. The reason why? It’s useful, and it’s also really old.

It is in fact a relic of an early stage of their common ancestral language, in which there was not yet the split between three genders of masculine, feminine and neuter. Instead, there were only two: animate (living and moving creatures) and inanimate (everything else).

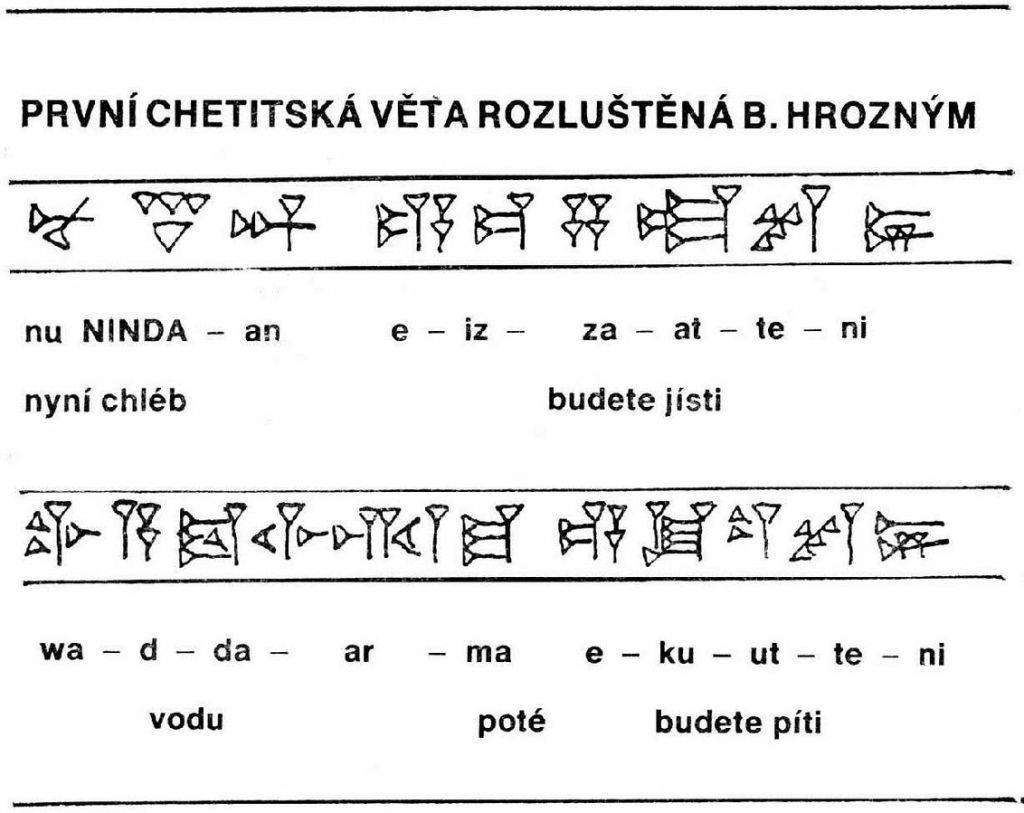

Only the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European family, including Hittite, was to maintain this two-way system as the norm. Everywhere else, a new three-gender split came to dominate nouns and pronouns, yet wh-words mostly evaded its influence. English who/what is therefore a relic from the earliest days of the Indo-European languages.

Note also how English who has the (archaic) form whom. It can change form according to its role in the sentence, e.g. subject who is watching? vs. object whom are you watching? This is a rare vestige of the system of cases that was once a key component of English grammar. Yet what can’t change – there’s no whatm to use in equivalent questions like whatm are you watching? This preserves an ancient feature of the old inanimate gender (also known as the neuter) that we observe across Indo-European, namely that neuter nouns are identical in both subject and object contexts. This offers us a cool and useful rule for learners that I’ve written about previously a few years ago.

4: He’s and It’s

In English today, we can add ‘s to a noun to show possession or some close relationship, as in Danny‘s post or a cat‘s whiskers. This affix isn’t added to pronouns though, since for them we use an alternative word. This is to say, the possessive forms of I and you aren’t I’s and you’s, but rather my and your. However, the possessive pronouns for he and it are his and its, which do end in that same S. This isn’t a coincidence.

Both possessive ‘s and the pronouns his and its are lasting legacies of an old genitive case, as is the feminine her. If we go back to Old English, the genitive case is hale and hearty, and masculine and neuter nouns were typically made genitive through the -s ending that we still see in his and its. So, the man’s would be þæs weres, and the child’s would be þæs ċildes. We see this same ending in Modern German, in which something of the man or of the child is des Mannes and des Kindes.

The fact that his, her and its are old genitives is part of an ancient split within Indo-European pronouns. We also find the same pattern elsewhere, in which third-person possessive pronouns are genitives, while first-person (my, our) and second-person (thy, your) possessive pronouns are or come from adjective-like words.

For instance, Latin meus ‘my’ and tuus ‘your’ change their endings to match the features of their associated noun, but eius ‘his/her/its’ is a genitive pronoun and does not change. Similarly, Czech můj and tvůj inflect to agree, but jeho ‘his/its’ and jejich ‘their’ resemble genitives and do not change their form. It seems that Proto-Indo-European in general had only specific pronouns for the first and second persons, and lacked them for the third person.

All this is to say that the -s of his and its is part of a long history and a wider story of how Indo-European languages form their third-person pronouns.

5: A Wonderful World of /w/

My final feature is a sound, a key phoneme across the many varieties of English. In words like wind, wave and of course word, we have the sound /w/.

It’s technically known as a voiced labio-velar approximant. This is not a strange sound for a language to have. It can be found today in Polish (e.g. biały ‘white’), Arabic (e.g. wāḥid ‘one’) and Italian (e.g. uovo ‘egg’) to name but three languages. What’s remarkable about English /w/ is that it seems to have been preserved from the days of Proto-Indo-European, unlike so many of its sister sounds.

Even in the absence of recorded audio, an assortment of evidence from across early Indo-European shows us that languages like Latin, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit once had the sound /w/. On this basis, we can propose that the sounds of Proto-Indo-European included the consonant *w too, which alternated with the vowel *u depending on its position in the syllable.

However, this ancient *w has often since been modified or lost. In Italian and German, it’s become a /v/ sound at the start of words, as in vino and Wasser. In Ancient Greek, we can see the sound dying out across its dialects, as the old Greek letter Ϝ disappears from our sources.

Meanwhile, many of the Indo-European languages that have /w/ today have developed it from other sources. As the letter shape suggests, the Polish Ł sound developed out of an original *l sound. The /w/ at the start of Italian words like uovo ‘egg’ and uomo ‘man’ is the result of vowel breaking, and these words go back to Latin ōvum and homō, without the sound there.

English is therefore unusual in that it preserves to this day the /w/ consonant that we believe Proto-Indo-European to have had. Besides English, its sister language, Scots, maintains it too – but beyond these two Germanic languages, it’s hard to spot other cases of the old *w of Proto-Indo-European. It seems that wending its way across the water to Britain may have saved the sound from phonological doom!

So, there you go! These are five linguistic antiquities still rattling around in the English language today. Like any language, English is a mixture of the old and the new. Amidst all the incessant changes through time, as each generation makes their linguistic inheritance their own, a handful of features have slipped by unnoticed and endured since the earliest known stages of the language. I don’t know about you, but this ancestry behind my language and the line of inheritance through millennia of generations are for me a powerful and humbling thought.

END.

References

- Ringe, D. A. (2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

Cover image: British Library, Harley MS 3271, page 85r. A wonderful Old English manuscript of Ælfric’s Grammar, here discussing the sounds of laughter haha and hehe!

Thanks for that Danny – interesting post on PIE relicts in English.

However stunned to learn that there is a Germanic language called Scots. I never knew(umlaut). Could you recommend a good grammar for Scots?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello!

I can recommend various resources about the Scots language, starting with the materials put up by the folks at the SCL:

https://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/node/id/553

If I may be so bold, I’d also like to share an episode of my new podcast, which kicked off with a discussion all about Scots with my friend Sarah, researcher and expert in the history of the language:

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/7fd7KlsZb4YmXuSQoMeIeP?si=67a48aa8694945ad

Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/scots-and-sarah-van-eyndhoven/id1703401848?i=1000624980838

Hope this is of use/interest!

LikeLike

Thanks for a very interesting post! I’d like to add that modern Dutch has preserved the /w/-consonant as well, with its pronunciation practically identical to the English w – and therefore rather different to the German w pronounced (a bit closer to) a v.

On the topic of words starting (mostly) with a w, Dutch question words like ‘wat’, ‘wie’, ‘waar’, ‘welk’, ‘waarom’ and ‘hoe’ of course strongly relate to their counterparts across Germanic languages, although the variation in sounds paired to meanings has always fascinated me. ‘How’ in English would translate to ‘hoe’ (pronounced as the English ‘who’) in Dutch, but to ‘wie’ in German; but ‘wie’ in Dutch (pronounced the same as the German ‘wie’) means ‘who’ in English…

Do you know about any research on (the changes of) those sounds/meanings?

Thanks again,

Jules

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jules!

Thank you for the question! The point about Dutch is a good one, although the sound in European Dutch is widely recognised as being /ʋ/ (made with the lips and teeth) today, and so Dutch too shows a shift away from /w/. However, the sound in Surinamese Dutch is a /w/, so again it looks like its emigration overseas saved the sound.

Mapping the different development of these question words is a mighty task! There’s been lots of research though, and essentially it boils down to specific sound changes in different Germanic languages, as well as some conflation of different words over time. Dutch ‘hoe’ and English ‘how’ are for instance a nicely related pair, and would sound the same, if it hadn’t been for English’s Great Vowel Shift in the early modern period. The relationship between ‘who/wie/wer’ is harder to account for though. While they share a common origin, the vowels have gone down different routes – possibly influenced by the R-sound that German wer still shows. In brief, it’s all complex and could benefit from a big table of changes!

LikeLike

Outside Germanic, Welsh has also preserved /w/ from PIE (though it becomes /gw/ at the start of words) and I think so has Persian.

LikeLike

Thanks for this little article, entertaining as usual. English is also one of the very few Germanic languages that preserved the TH sound(s) all the way from Proto Germanic, i.e. since the time of Grimm’s Law. The only other of its Germanic siblings to preserve it/them (to the best of my knowledge) is Icelandic—again sharing the trait of being spoken on an island!

LikeLiked by 1 person