The Wonderful World of *walha–

Reading time: 10-15 minutes

This article is an adaptation of one first written for the brilliant interdisciplinary magazine Porridge, which you can find out more about at porridgemagazine.com. Note that an asterisk * is used for historically undocumented and therefore hypothetical words.

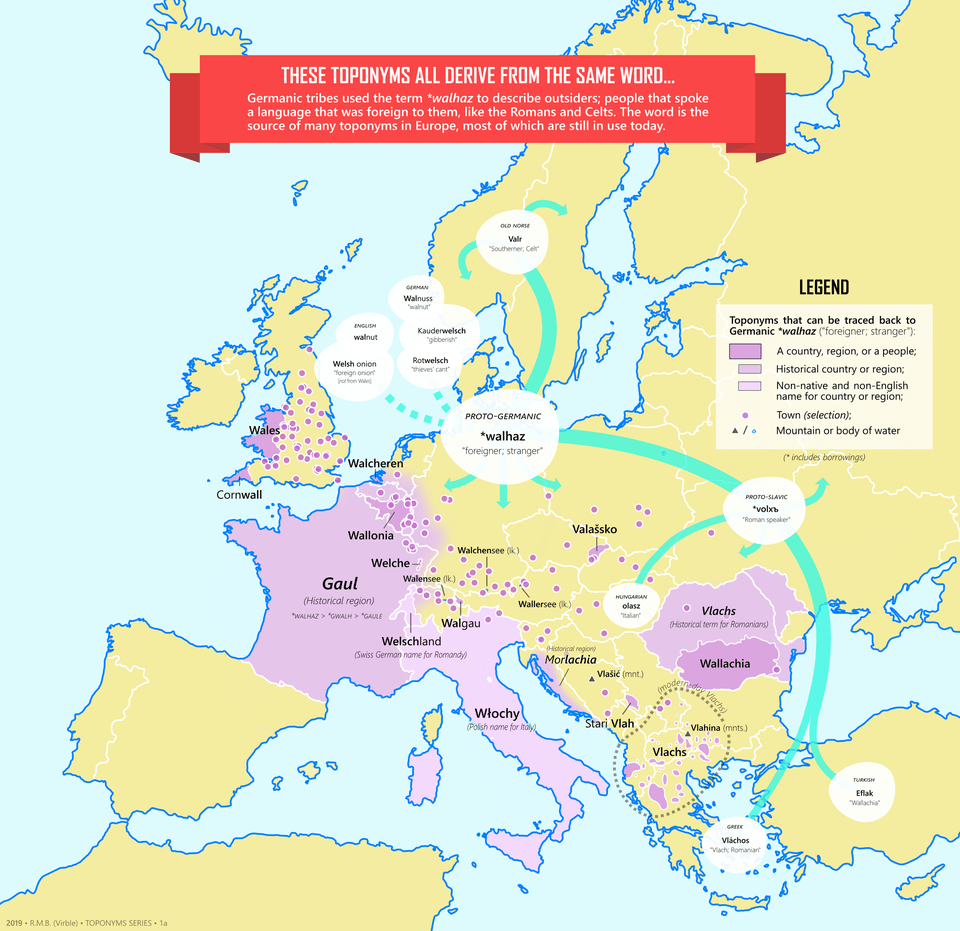

I’d like to tell you the tale of a headlong tumble down a rabbit hole of etymology and European history, that has at its centre a wandering word with a reach wide enough to unite a continent.

It begins, like all good stories, with a map. The map, given below, gives the (spoken) words for Italy across many modern European languages.

When I first came across this map online, one glaring anomaly stood out for me. While I was not (and am never) surprised by the uniqueness of Hungarian, Polish Włochy seemed an unexpected and inexplicable name for Italy. The little voice that lurks at the back of the etymologist’s brain immediately piped up to ask, quietly but firmly, ‘but where does that come from?‘

Part I: Slavic

My go-to sources suggested an origin as far back as Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed ancestor of all of the Slavic languages, which today include Czech, Polish, Russian, Bulgarian and many others. The original word in the ancestral language was *volxъ. Note that the letter ⟨x⟩ here represents that fricative sound at the back of the mouth found in the Scottish word loch.

Having been dated to that far back in time, I expected there to be Slavic sister-words of Włochy with the same origin. Sure enough, I found several, such as Russian volóx and Bulgarian vlah, as well as those that had migrated during the medieval period out of the Slavic family and into neighbouring languages, such as Hungarian olasz and Greek vlákhos.

However, unlike Hungarian olasz and Polish Włoch, some of these other Slavic words do not mean ‘Italian’, but rather ‘Vlach’, a term with a long and complex history.

In current English at least, to be a Vlach is to be a speaker of a Romance language (i.e. a linguistic descendant of Latin) east of Italy and south of the Danube. This excludes Romanians, but historically it could refer to the Romance speakers on either side of the river. The word led to the exonym Valahia, the land of the Vlachs.

Today Valahia is a region in Romania, the English word for which is Wallachia, and which was ruled in the fifteenth century by the (in)famous Vlad III Dracula. Many Vlachs lived nomadic lives, following their flocks of sheep over the Balkans and Carpathian mountains; indeed, they reached so far west that the traditional name of the easternmost part of the Czech Republic is Valašsko. In Slovak, profession evidently eclipsed ethnicity and language, as valach now simply means ‘shepherd’.

But what links Italy to the Vlach people? Language must be the key, since both Vlachs (at least traditionally) and Italians speak Romance languages.

Was ‘Romance speaker’ then the meaning of *volxъ? This must be our intermediate conclusion – far from satisfactory, as we still lack the origins of *volxъ itself. To do so, we must go much further back.

Part II: Julius Caesar

It is the middle of the first century BC. Gaius Julius Caesar is waging war against the inhabitants of Gaul and sensationalising the events for the audience at home. He records the (Latinised) name of one people, the Volcae, who we presume would have spoken a language of the Celtic family, and who seem to have inhabited a large territory across modern-day France, Switzerland, southern Germany and into the Czech Republic.

The name that they themselves used would have been something along the lines of *wolka-. Scholars believe this in turn to derive from an earlier word meaning ‘wolf’ or ‘hawk’, but let’s take simply the term *wolka- as our point of departure.

To the north at this time were people whose language was the ancestor of the Germanic languages (today including English, German, Dutch, Swedish and others). We therefore call their language Proto-Germanic, and it was into an early stage of this language that *wolka- crossed over as the name for their southern Celtic-speaking neighbours.

We must presume an early stage, because the word undergoes the same sound changes that would affect the rest of the language. These changes, captured by Grimm’s Law (the work of Jacob Grimm, better known for collating fairy tales), include the shift of an original *k sound into a fricative *x.

This affected *wolka-, producing a Germanic noun: *walha-.

Part III: The Meaning of *walha–

Though only a reconstruction and necessarily a hypothesis, we can at least feel confident about the shape of the Proto-Germanic word *walha-. Its meaning, on the other hand, is a matter of some debate.

If we accept its original reference to a Celtic-speaking people, we must also believe that its meaning would go on to change – in my mind, from ‘Celtic’ to a widespread use as ‘Latin speaker’ or ‘Roman’, since this is how the word’s descendants so frequently enter the historical record.

One theory is that this was a simple switch, Celt to Roman, caused by the Romanisation of the Volcae and other Celtic-speaking peoples of the Alps and southern Germany.

Over time, the Volcae were absorbed into the structures and identity of the Roman Empire. That absorption would have linguistic too. The Latin language, expecially in western Europe, would have been part of the package deal of Roman identity. As the centuries passed, the people of southern Germany would have increasingly looked and sounded to northern outsiders like simple Romans.

The strong and popular alternative is to suggest a semantic expansion of the word from ‘Celt’ to ‘foreigners’ more generally. This would naturally include the Romans.

These two theories of meaning – narrower ‘Roman’ versus broader ‘foreigner’ – are well established. Each must be borne in mind when discussing the many descendants of *walha-.

Personally, I’ve come to think that both the linguistic evidence and Occam’s razor support the former: the meaning of simply ‘Roman’ or ‘Latin/Romance speaker’. I believe that what has traditionally been translated as ‘foreigner’ could equally, without difficulty, be translated as ‘Roman’.

To do so coheres with the evidence and renders the ‘foreigner’ stage unnecessary. That famous Franciscan’s razor can then be deployed. ‘Celt into Roman’ is certainly a simpler argument than to say that ‘Celt’ changed into ‘sometimes Roman, sometimes not, though cases of the latter are ambiguous’.

Part IV: *walha- Arrives in Britain

Let’s examine some examples.

Our term *walha- travelled with the Germanic migrations of the later imperial period. By means of the Goths and their own Germanic language, the word passed from Proto-Germanic into Proto-Slavic. That language recast it as *volxъ. This is a proto-word whose descendants we have already seen to have the restricted meanings of ‘Romance speaker’ and of people who would historically have regarded themselves as Roman-ish.

Wealh, another of the descendants of *walha-, was an Old English word applied to the Romano-British population of Britannia. Its plural form, wealas, would become Wales. Moreover, the adjective that Proto-Germanic derived from *walha– was *walhiska-, and it was from this that English gets Welsh.

In contrast to this, the Welsh use variations on Cymr- to describe themselves (e.g. Cymru ‘Wales’, Cymraeg ‘Welsh’), from an older Celtic word meaning ‘compatriot’.

Furthermore, the element Wal- that is present in many English place names, such as Walton, Walpole and Walworth, is likely a form of wealh, which we can take as evidence of the survival of distinctly Romano-British communities.

The Romano-British in the south-western extremity of Britain may have additionally gone by a local name like *Korno-, with the possible meaning of ‘the people of the peninsula’. Resultantly, in Old English, these people would have been the Cornwealas, whose descendants inhabit Cornwall today.

Perhaps it’s the old narrative of a British underclass and a ruling Roman elite (who abandon ship in 410 AD and take all the culture with them) that has led scholars to propose that Old English wealh meant ‘foreigners’ in general. This story assumes that the Britons who remained were still proud Celts at this point, not Romans.

This narrative is nowadays rightly besieged on all sides; the people of fifth-century Britain would have certainly thought of themselves as Romans and Latin would have been widely spoken, especially in the south. The incoming Germanic-speaking migrants would also have recognised this.

Indeed, there is a divide in our Old English sources between the terms Wealas and Cumbere. The latter seems to be restricted to northern people and events (hence Cumberland in northern England), and the two terms may reflect a perceived difference “between the Romano-British population they encountered in the south … and a more barbaric, less Romanized population in the north” (Woolf 2010: 232).

On this basis, it’s not necessary to expand the development of wealh beyond ‘Roman’ and into ‘foreigner’.

In favour of ‘foreigner’, however, are a handful of words like Old English wealhstod ‘translator’, perhaps very literally ‘the one who stands on behalf of the foreigner’. Yet this term likewise looks to have emerged in the British linguistic context and from the contact between Britons and the newcomers. It even gets borrowed into one of the opposing languages, Welsh, as gwalstod. The humble walnut, from Old English wealhhnutu, could possibly support either meaning, as ‘the foreign nut’ or ‘the Roman nut’, i.e. the nut from Roman lands.

As a final note, I don’t deny the idea that wealh had other meanings; in some sources, such as Old English translations of the Bible, wealh means ‘slave’, which might reflect an unequal relationship between the Germanic and British social groups.

My sense, however, is that this was an Old English innovation, changing sometime after the language’s arrival in Britain. All things considered, it looks like the Wealas were first and foremost Romans.

Part V: *walha– on the Continent

Elsewhere in Europe, other terms derived from *walha- gained currency. The Franks, a Germanic-speaking people who built up an enormous empire on both sides of the old empire’s border, applied their derivative of the word to the Romance speakers of western Europe that they would eventually rule.

Their word crossed over into the Romance family itself, specifically Gallo-Romance, creating French wallon ‘Walloon’ and Wallonie ‘Wallonia’ (the Romance-speaking part of Belgium), as well as Gaule, whence comes English Gaul, the ancient home of Astérix.

In a coincidence that defies easy belief, although the term Gaul refers to the exact same region known to the Romans as Gallia, Gaul and Latin Gallia are not in fact etymologically related – a rare accidental similarity. While Gaul comes from Frankish and ultimately *walha-, Latin Gallia and Gallus ‘a Gaul’ have a Celtic origin, likely the same one as Celt and Galatia.

Moving back to predominantly Germanic-speaking lands, *walha- produces Old Norse valir ‘the French, Gauls’, whose country, Valland, appears in Norse legend. Valland could translated as the ambiguous ‘land of foreigners’, but, assuming the alternative, narrower meaning, it could simply refer to the Roman Empire.

To the south, the adjective welsch crops up in many varieties of German; though once used more widely, welsch is now limited to Swiss German and is typically taken as derogatory. It is used for those parts of the country that are, once again, Romance-speaking (in this case French, Italian or Romansch).

The term also survives in both current and defunct place names. The autonomous province of Trentino, today a northern part of Italy, has for centuries been either associated with or officially a part of the Alpine region of Tirol. Trentino is traditionally Italian/Romance-speaking, and so, for German speakers further north, it was known as Welschtirol.

Another example is Welschbern, an archaic German name for Verona in Italy, with Welsch– probably prefixed to Bern to distinguish it from the Swiss Bern to the north.

To Conclude

Walnuts, Vlachs, Wallons, Welsh and Gauls – this is a lot of information, and yet I could include more descendants of *walha-. In terms of usage and distribution across space and tongues, *walha- has been surprisingly successful.

After all, the word is not a personal pronoun, common verb or some other vital piece of grammar, but simply a noun with a limited ethnolinguistic reference. This prolificity is, I suppose, what comes of attaching oneself to a concept as potent as Romanitas.

While I hope I have provided good evidence to support my belief that *walha– had an narrower, exclusive meaning: ‘Celtic-language speaker’ then ‘Roman’, but not ‘foreigner’. I am aware that the theory is not without its complications. My hope is that the examples above will help you to make up your own mind. Yet this theory is not the principal idea behind the creation of this piece!

What I really want to impart to you are not half-baked historical ramblings, but a sense genuine joy. The journey into the world of *walha– that began with pulling at the thread of Polish Włochy was exciting in its surprises and delightful in the network of links and patterns that emerged.

No one would never dispute the interconnectivity of words across countries – but to focus on a word so prolific (and yet with offspring still infrequent enough to be interesting) is surely the best means of appreciating this phenomenon. Each descendant of *walha– is a thread that, though unique and interesting in its own right, helps to tie Europe together.

What a pleasure it is to appreciate how we can connect Wales to Romania, Italy to Poland, and France to walnuts! In my mind at least, *walha– is a word able to make Europe feel that little bit more united, and far-off affairs that little bit less foreign.

END.

Selected Bibliography:

- Faull, M. L. (1975). The Semantic Development of Old English wealh. Leeds Studies in English 8; 20 – 44. University of Leeds.

- Mills, A. D. (2003). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press.

- Schrijver, P. (2013). Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages. 19 – 20 Routledge.

- Woolf, A. (2010). Reporting Scotland in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Reading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Language, Literature and History. 221-239.

This is fascinating (as usual), and perhaps sheds some light on the mysterious origins of my (Slovak) great-grandmother’s family. It was always rumoured that Maria Valuch (sometimes Valach) had “gypsy blood.” Her family did not have sheep, rather horses and a fair amount of money and land. Maybe some of her forefathers and -mothers wandered north from those latinate regions? Food for thought. I think I’ll have some walnuts and ponder.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Merci bien, vous avez fait un bon travail pour le Tribu WALHAZ. Mon nom de famille est WALHAZi. Je suis un Tunisien.Il existe le Tribu WALHAZ en Tunisie.

LikeLike

The name that they themselves used would have been something along the lines of *wolka-. Though many believe this in turn to derive from an earlier etymon meaning ‘wolf’ or ‘hawk’, let us take simply *wolka- as our point of departure.

Doers this also account for the English word folk?

LikeLike

The name that they themselves used would have been something along the lines of *wolka-. Though many believe this in turn to derive from an earlier etymon meaning ‘wolf’ or ‘hawk’, let us take simply *wolka- as our point of departure.

Would the English word folk also derive from this source?

LikeLike

Another toponym to consider is Wauchope, Dumfriesshire, Scotland, and its derivatives such as Wauchope Forest found on Google Earth. One etymology for Wauchope is Anglo-Saxon “walh hop” or “valley of the foreigners/Welsh”. As for being a possible reference to Britons or Romanized Britons, observe that the region is about 50 km north of Hadrian’s Wall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting! One thought that comes to mind from this interpretation given the map is that it seems to have come to mean romance-speakers specifically rather than romans subjects in general (except the Welsh), in that the Greek speakers would also be romans (Romioi)

LikeLiked by 1 person