Reading time: 10-15 minutes

To hear me speaking in my not-quite-best Latin, you can listen along here:

IF you know a thing or two about Roman history, you will have come across the Gauls. They loom large in the story of Rome’s rise to dominance, both as their aggressor and as victims of their conquests.

In its early days, when Rome was a little Italian kingdom and then a republic, Gauls would come to be found on both sides of the Alps, having migrated from what is now France into northern Italy in the 4th century BC. This expansion brought them into intense contact with the Romans. Some of this contact was at the point of a sword. In 390 BC, a Gaulish army defeated a Roman force at the Battle of the Allia and then, in an event that haunted the Roman imagination for centuries to come, sacked the city of Rome itself. Wind forward the clock to the 1st century BC, and we find the Romans now on the attack, as Julius Caesar wages his infamous wars and brings all Gaul under Roman control – with the exception, according to one somewhat historical source, of a single indomitable village in Armorica. Yet among these hostilities, there must also have been peaceful cooperation, such as through trade. In brief, contact between Romans and Gauls was long-lasting and profound.

Here’s the thing: because of this contact between peoples and languages, many Gaulish words made their way into Latin. Having successfully diffused into Latin vocabulary, some of these words have since journeyed further, via Latin into English. Hence, if you know English, you’ll actually know a bit of Gaulish!

Knowing about Gaulish is an important component of the English etymologist’s toolkit, so it seemed like a good idea to me to write a piece for this month that highlights its contribution to English vocabulary. To keep it simple, I’ve chosen ten words that I reckon are individually interesting, but also together demonstrate the influence of Gaulish on our Latinate lexicon. For each, I’ve laid out a little of what we know about its history and how we can link the word back to the Gaulish language of the classical era.

A word of caution though: these journeys are fraught with etymological danger. Our surviving sources for Gaulish are minimal, so it is often invoked as only the most likely origin for a word. This we can do on the basis of where, when and in what context it first appears the written record (e.g. in Latin or French), and by cross-referencing it with languages closely related to Gaulish for which we do have lots of evidence.

So much of our understanding of the Gauls comes from Roman sources and therefore a Roman perspective. The Gauls had only a very limited culture of writing, so our information about them is more than a little skewed. The English term Gaul follows Latin Gallus, a label imposed from the outside on a historically and geographically vast variety of people, and implying a unity and uniformity that the ‘Gauls’ themselves may not have recognised.

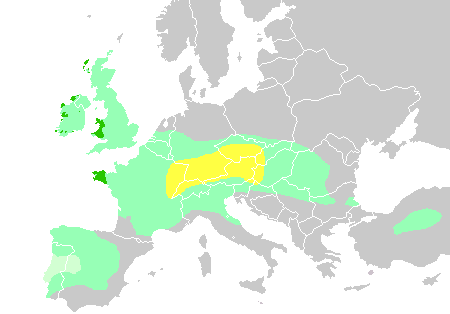

Yet something that they do seem to have had in common is language. Specifically, we can tell from archaeological finds, place names, and words and personal names in Latin sources that what they spoke was part of the Celtic language family. This makes Gaulish a continental cousin of Welsh and Irish, two of the Insular Celtic languages. So, while Gaulish no doubt had its divisions and dialects, and to say that a word has an origin in ‘Gaulish’ is probably a gross simplifcation of the real linguistic situation, it will have to do as an umbrella term for the Celtic language of France and northern Italy in the classical era.

With all that in mind, through an assortment of ten words, allow me to demonstrate how much Gaulish you actually already know!

1:

embassy

To kick off this list, I’ve chosen to be diplomatic. Embassy, not too surprisingly, is a word that English gets from French, along with the person who works there, the ambassador. These find their origin in Latin ambactus, an uncommon word that refers to a kind of personal attendant or subordinate. When Julius Caesar describes the aristocracy of Gaulish society, he writes that members of the social class of ‘knights’ (equitēs) have

“… plūrimōs circum sē ambactōs clientēsque…”

‘… the most vassals and followers around them…’

(The Gallic War 6.15)

Ambactus is thought not to be native to Latin, but rather to be a borrowing of a Celtic word, one that included the prefix *ambi- ‘around’. Perhaps Caesar even used ambactus specifically because it still had Gaulish associations!

2:

carpentry

While carpentry today concerns woodworking in general, a carpentāria in Roman times was where wagons and chariots were made. The root of this Latin word is carpentum, itself considered to be of Celtic origin. Helpfully for us etymologists, the Roman historian Livy even uses the word in a Gaulish context, when he writes of how a victorious Roman army came away

“… carpentīs Gallicīs multā praedā onerātīs plūs ducentīs…”

‘… with more than two hundred Gaulish chariots, burdened with much loot…’

(The History of Rome 31.21)

The same Celtic root that produced carpentum would also become carpat in Old Irish, a kind of war chariot.

3:

gladiator

Roman gladiators got their name from their use of a gladius, originally a specific kind of double-edged sword, which became standard issue in the Roman army. The word gladius is thought to come from a Celtic language, such as Gaulish. One reason is that we find an apparent cognate of it in Old Irish: claideb. This likewise means ‘sword’, and it’s the origin the Scottish great sword, the claidheamh mòr, or claymore. All in all, a Celtic pedigree for gladius and thus gladiator seems reasonable.

4:

denim

It’s a wonderful and widely known etymological fact that denim is the material that comes de Nîmes in France. Yet where does the city of Nîmes get its name from? To the Romans, it was Nemausus. Prior to its refounding by Augustus as a colony and Roman city, it was the principal settlement of the Volcae Arecomici, a Gaulish people, and the name looks to contain the Celtic root *nemeto-, referring to a sacred space centred on a natural spring. So, even in the denim of your jeans is a legacy of Gallo-Roman relations.

5:

mutton

Thanks to Celtic words for ‘male sheep, wether’ like Welsh mollt and Irish molt, we may reconstruct the common Celtic word *molto-. A Gaulish descendant of *molto- can offer a source for further words like Italian montone (‘ram’) and French mouton. From the latter, English gets its word for the meat of an adult sheep, mutton.

6:

battle

According to the theories of how Latin’s sounds developed, we do not expect native Latin words to begin with a B. Plenty of Latin words of course do have an initial B, but many among these B-words are thought to be borrowings from other languages. Battuere ‘to hit’ is one such word. It does not appear to be native to Latin, so a Celtic (specifically Gaulish) origin has been suggested. From battuere subsequently came battuālia – the ‘hitings’, referring to the practice fights of gladiators and soldiers. This in turn, via French, has given English battle, while battuere is also behind battalion, battery and the striking arguments of a debate.

7:

beak

The Gauls also seem to be responsible for the beak of a bird! Beak and the French word from which it immediately derives seem to descend from Latin beccus. This is a very rare word in our Latin sources, appearing to my knowledge only once. Yet in that single attestation, it has a connection to Gaul. The Roman historian Suetonius, describing the violent end of the emperor Vitellius, writes that the event in fact fulfilled a prophecy.

“… quī auguriō, quod factum eī Viennae ostendimus … praedīxerant quam ventūrum in alicuius Gallicānī hominis potestātem; sīquidem ab Antōniō Prīmō, adversārum partium duce, oppressus est, cui Tolōsae nāto cognōmen in pueritiā Beccō fuerat: id valet gallīnāceī rōstrum.“

‘… those who, by the augury that we mentioned happened in Vienne, had predicted how he would be captured by a man of Gaul; since indeed he was seized by Antoninus Primus, a general of the opposing faction, who was born in Toulouse and in childhood had the nickname Beccus – which means ‘chicken’s beak’.

(Vitellius 18)

Suetonius very helpfully gives a Gallic background to this nickname, and a definition too for presumably what was yet to become a common Latin word.

8:

lawn

Lawn has carelessly lost a consonant over the modern history of English. If we go back to the medieval and early modern state of the language, the word is laund. This better shows its connection to another outdoorsy word: land. While the latter is inherited from Germanic, laund comes from French. Where French in turn borrowed it from is not certain, as we have two choices: also Germanic or Celtic. Some authorities, including the OED, derive it from a Celtic source, specifically Gaulish. We know that the same land-root existed in early Celtic as well as Germanic, because it’s the source of the Welsh word llan that is so often found in Welsh place-names.

(Llan has gone on its own fascinating journey too, changing in meaning from ‘land, plot of land’ to ‘church’s land, churchyard’ to ‘church, parish’!)

9:

piece

Piece is an ordinary enough word in English, yet its origins beyond its first appearances in Old French are mysterious. The general consensus is that it’s the product of an unattested Latin word *pettia, and this was a borrowing from Gaulish. The Insular Celtic languages support this idea. In Welsh, we find the similar-looking peth, meaning ‘thing’ or ‘material’, while Irish has the related word cuid, meaning ‘portion, part’.

10:

car

To top the list is the automobile itself, the common car! It’s a word that English gets from Old Northern French, alongside chariot from Old French to the south. These go back to Latin carrus, a kind of wagon, and a word used by Caesar several times in his account of the Gallic Wars.

“… ūnum per Sēquanōs, angustum et difficile, inter montem Iūram et flūmen Rhodanum, vix quā singulī carrī dūcerentur…”

‘… one (route) through the Sequani, narrow and difficult, between Mount Jura and the river Rhône, by which one wagon at a time could barely be led…’

(Gallic War 1.6)

Not only do we have this Celtic context for the early appearances of the word in Latin, we also have a Celtic-looking place name (“Karrodounon“) mentioned by the geographer Ptolemy, and the word carr in Middle Welsh and Old Irish, in which it means ‘cart’. All in all, car is an old Gaulish word that’s been recently very successful in its usage!

So, there are my ten words! I hope they succesfully illustrate the influence of Gaulish on Latin, and the languages that Latin has greatly influenced in turn. They are quite a diverse group of fairly everyday words, not limited to specific aspects of Gaulish society or culture. Such words therefore speak to me of the intensity and longevity of contact between the two languages. Although Gaulish was doomed to die out and be replaced by Latin, it did endure as a vernacular language for a few centuries. During that time, it seems its speakers made a mark on the vocabulary of the newcomer, and have left quite a lexical legacy in English.

Yet, despite all that, one word that Gaulish doesn’t seem to have given English is Gaulish.

END.

References

- Blažek, V. (2008). Gaulish Language. Studia minora Facultatis philosophicae Universitatis Brunensis / Sborník prací filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity, issue 13.

- Matasovic, R. (2008). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill.

- Mullen, A., & Ruiz Darasse, C. (2019). Gaulish: Language, writing, epigraphy (Vol. 6). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

- Stifter, D. (2020). Cisalpine Celtic. Languge, writing, epigraphy (Vol. 8). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

- Trask, L. (2009). Why Do Languages Change? Cambridge University Press.

- OED.com

- Nîmes et la romanité. (Vous voyez le topo website)

Cover image taken from The Times article Retire Asterix? Of all the Gaul

Is there no connection between “carpentum” and “car”?

LikeLike

Those super long Welsh place names seem like they described it more than named it. Kind of like how in German you can squish words together to make a new word.

LikeLike