Reading time: 5 minutes

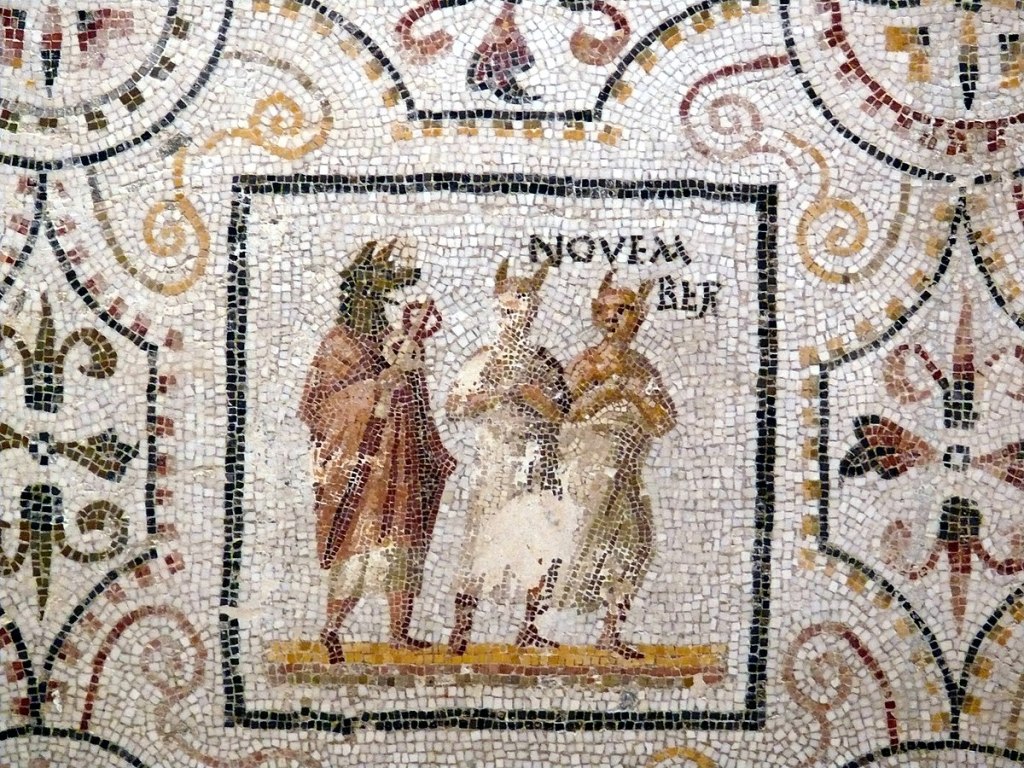

November, at time of writing, is ticking out its final few hours, and with them, the eleventh month of 2024 is giving way to the twelfth.

Aside from the awkward mismatch in the months’ etymology (November and December were originally the ninth and tenth months in the Roman calendar), the numbers that the months correspond to are curious anomalies within English vocabulary.

English numbers are generally very logical. They operate within a decimal system, counting up in multiples of ten. Twenty precedes twenty-one, itself preceding twenty-two. When English speakers reach the end of one ten, we move on to the next, progressing from the twenties to the thirties, from the thirties to the forties, and so on. Yet there are two flaws in the diamond, which appear early on in the system.

Why does English have eleven and twelve? Why not oneteen and twoteen, to match thirteen and the rest?

These two numbers don’t follow the -teen pattern of their seven decimal companions. The presence of two equivalent outliers, I should add, is by no means universal or even the norm across languages. In Czech and Hungarian, to give two European examples, eleven (jedenáct and tizenegy) and twelve (dvanáct and tizenkét/tizenkettő) stand in harmony with the rest of the teens.¹

The connection of eleven and twelve to the corresponding pre-ten numbers is also weak – twelve does at least share the TW of two, but eleven seems utterly removed from one. What then are the origins of eleven and twelve as words?

This post is dedicated to the question of where English got eleven and twelve from. The answer involves both the familiar and the logical, but also the unfamiliar and the mysterious.

We can begin the etymological journey back in Old English, from which our modern numbers and their decimal patterns derive.

However, even at this early point in time, the inconsistency is already present. The numbers in question are endleofan and twelf. For comparison, one and two in Old English are ān and twēgen. There are more similarities to be noted though; the number endleofan does at least contain the N of ān.

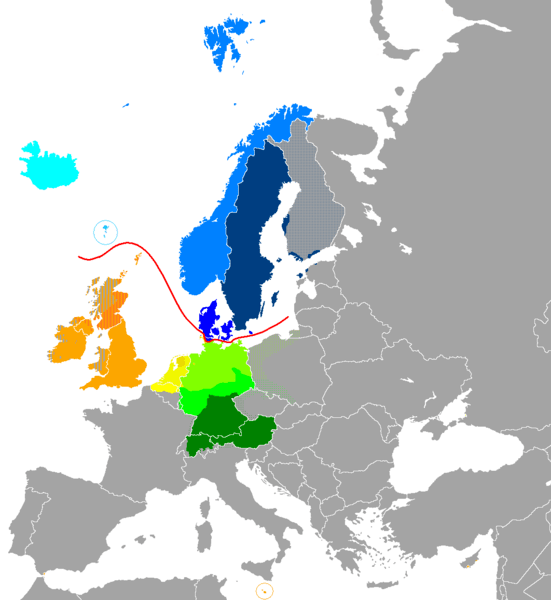

These numerical oddities are not limited to English though. We find corresponding cognate numbers and the same disharmony across the Germanic languages, such as with Dutch elf and twaalf, German elf and zwölf, and Norwegian elleve and tolv.

With this distribution across the linguistic cousins, we have the means to reconstruct the two distinct numbers back to the languages’ common point of departure, Proto-Germanic.

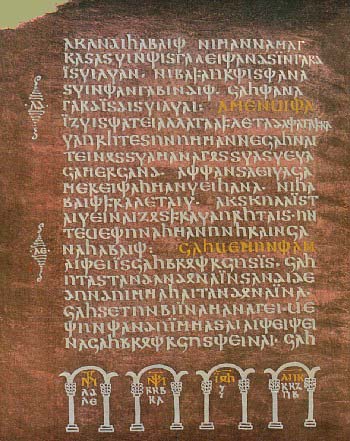

Gothic, the oldest well-documented Germanic language, is particularly important in the task of reconstruction. In Gothic texts, we find the numbers 𐌰𐌹𐌽𐌻𐌹𐌱𐌹𐌼 (ainlibim) and 𐍄𐍅𐌰𐌻𐌹𐍆 (twalif).²

“𐌾𐌰𐌷 𐍅𐌰𐍂𐌸, 𐌱𐌹𐌸𐌴 𐌿𐍃𐍆𐌿𐌻𐌻𐌹𐌳𐌰 𐌹𐌴𐍃𐌿𐍃 𐌰𐌽𐌰𐌱𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰𐌽𐌳𐍃 𐌸𐌰𐌹𐌼 𐍄𐍅𐌰𐌻𐌹𐍆 𐍃𐌹𐍀𐍉𐌽𐌾𐌰𐌼 𐍃𐌴𐌹𐌽𐌰𐌹𐌼…”

Jah warþ, biþe usfullida Iesus anabiudands þaim twalif siponjam seinaim…

‘And it came to pass, after Jesus had finished instructing his twelve disciples…’

Wulfila’s Bible, Matthew 11.1

On the basis of the historical and family-wide evidence, the numbers eleven and twelve have been reconstructed back to two prehistoric Proto-Germanic numbers: *ainalifa– and *twalifa-.

What we have here are two ancient compound words, each made up of two elements. The first part is a smaller number. As we might expect, these are the Proto-Germanic words for ‘one’ and ‘two’, namely *aina- and *twa-.

On its own, *aina– would become Old English ān, and eventually the modern number one. Meanwhile, by being included in the prehistoric compound word for ‘eleven’, the same word would progress down a different path of sound development in the emerging English language.³ The result is that the initial E of the modern word eleven is in fact a much reduced twin of the number one.

So, with this Germanic etymology in mind, eleven and twelve are not so strange after all. Like the rest of the teen-team, they originally contained the basic numbers one and two, plus something else. Subsequent sound changes then obscured this ancient logic.

What though was that “something else”? What was the meaning of the *-lifa– bit of the reconstructed numbers *ainalifa– and *twalifa-, still present today in eleven and twelve?

This element is explained as a form of the ancient verb *līban-. This meant ‘to stay, to remain’. The theory goes that eleven and twelve were originally compounds meaning something like ‘one-left’ and ‘two-left’. The thinking behind this was that an eleventh or twelfth thing was something left over after counting up to ten, possibly on the ten digits of one’s hands.

This view of eleven and twelve as surpluses over ten, rather than additions to it, is an unfamiliar way of thinking about the numbers. It contrasts with the ‘X plus ten’ derivation of the numbers from thirteen to nineteen.

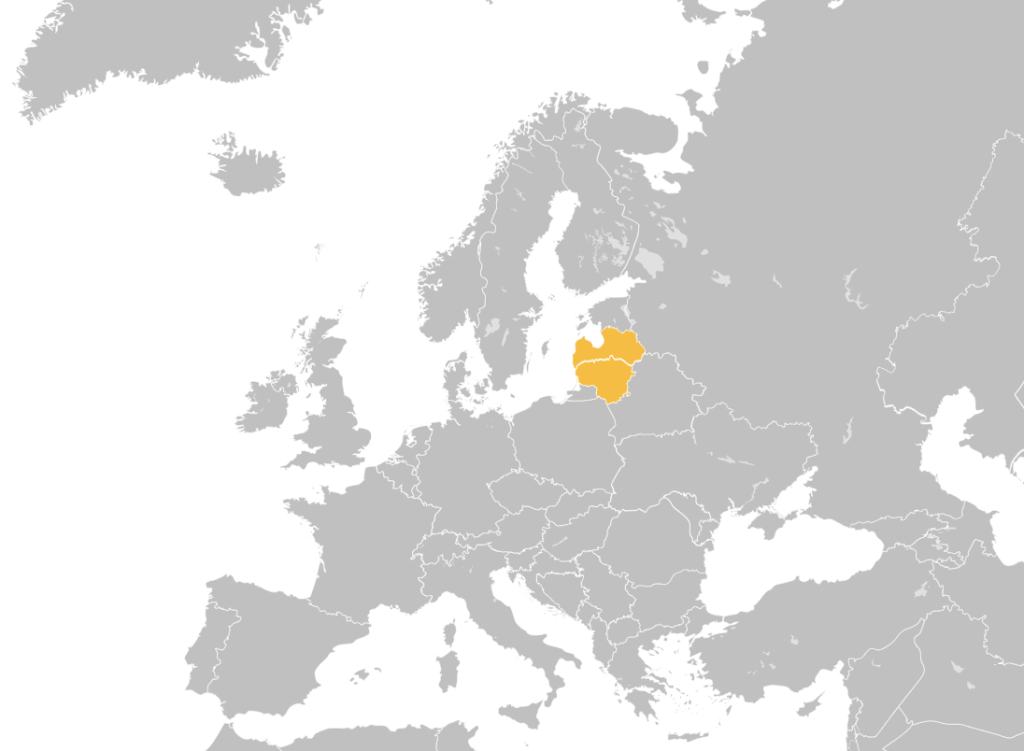

It’s even been suggested that this concept of ‘one-left-over-from-ten’ and ‘two-left-over-from-ten’ was a system partly adopted by Proto-Germanic speakers from an unknown and unrelated language of northern Europe. Supporting this theory is the fact that the same concept seems to be present in Lithuanian counting too.

This Baltic language forms all of its numbers from eleven to nineteen with -lika. In Lithuanian, ‘eleven’ is vienuolika, ‘twelve’ is dvylika, ‘thirteen’ is trylika, and so on.

This –lika element is related to the Lithuanian noun liekas ‘extra, leftover’ and the verb likti ‘to remain’.

The system seems to have been far more vibrant and productive over the history of Lithuanian, compared with the two fossils in Germanic languages.⁴ It is unclear whether Proto-Germanic once had the option to compute all the teen-numbers this way, or for some reason only adopted the lowest two numbers from the system, which have managed to survive until the present day as eleven and twelve. Or maybe it’s just a coincidence.

Together, the Germanic languages and Lithuanian offer examples of an alternative way to reckon the numbers between ten and twenty. They may therefore offer evidence for a possible common source of inspiration.

That common source must remain extremely mysterious, otherwise completely concealed by the mists of time, if it even existed at all. However, one thing is sure: that interesting etymologising can lie behind English vocabulary as basic as eleven and twelve!

END.

Footnotes

- This is not to say though that all other languages are completely consistent with their teen-numbers. There is tremendous variety, even within Europe alone. Within the Romance languages, for example, there’s a distinct break in their composition at or after sixteen, when the -teen component switches to precede the smaller number. Compare French seize (16) with dix-sept (17), or Portuguese quinze (15) with dezasseis (16). This modern variety contrasts with the situation in the languages’ common ancestor, Latin, which could add -decim to form all the numbers between eleven and nineteen, or use the formation ‘X from twenty’ for eighteen (duo-dē-vīgintī) and nineteen (ūn-dē-vīgintī).

- Interestingly, in Crimean Gothic, the language of the Black Sea attested in a handful of words centuries later, eleven and twelve are thiinita and thunetua. It may be that Gothic later got rid of the old numbers, in favour of new compounds that were more transparent in their composition.

- Various sound changes took place that turned Proto-Germanic *ainalifa– (or *ainilifa-) into Old English endleofan. These include the process of i-umlaut, which affected the word’s initial vowel, and the epenthesis of D between N and L. The final N of endleofan, still present in eleven, has been explained as an influence of the neighbouring number ten.

- In Old Lithuanian, liekas as a separate word could also create ordinal numbers, and on its own could mean ‘eleventh’. For Eric Hamp (1972), this commonality between Germanic and Lithuanian is not a product of contact with some spooky third language in the forests beside the Baltic Sea, but rather of their common Indo-European heritage.

References

- Fulk, R. D. (2018). A Comparative Grammar of the Early Germanic Languages (Vol. 3). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hamp, E. P. (1972). Lith. liekas. Baltistica. 8(1). 55-6.

- Kroonen, G. (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto–Germanic (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series 11). Brill.

All images taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Could one and two left over be due to the concurrent use of two counting systems – base 10 and base 12? One gives us our current hundred (100) and the other gave us the long hundred (120) as well as the labels dozen and gross.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not aware of a long hundred (or a long ton) outside of English. Dozen and gross are from French, though (where they’re obsolete now).

LikeLike

https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundare

https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stor-hundra

The first link includes the suggestion that the hundreds (organisational units) in Svealand had to provide 8×12 warriors.

The second includes a link to an 1882 reference book that lists several examples of the use of 12 in counting.

LikeLike

https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundare

https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stor-hundra

The first link includes the suggestion that the hundreds (organisational units) in Svealand had to provide 8×12 warriors.

The second includes a link to an 1882 reference book that lists several examples of the use of 12 in counting.

LikeLike