Reading time: 5 minutes

When we look at impressive Latin inscriptions from the days of Rome, there is something very fixed and familiar about the look of the letters. We recognise the roughly square-shaped capital letters like A, B and C as our own, and they more or less serve the same functions now as they did for Julius Caesar.

The designs, uses and order of Rome’s letters came to be settled between the third and first centuries BC. The story of the Latin script since then has generally been one of continuinity, adjusting and modifying its classical form, rather than overhauling or making major additions to it. You’d be forgiven for thinking that the alphabet had always looked that way.

Yet the classical appearance of the Latin alphabet did not emerge fully formed. Rather, it developed in gradual stages, links in a chain of alphabetic acquisition and adaptation that connected Roman writing back to Egypt. Archaeology has offered examples of the Latin script’s pre-history, which look increasingly less familiar the further back you go.

However, we don’t need to go digging for rare finds from Rome’s early years to find these differences. Some of these alien alternatives to our capital letters in fact lived on beyond the establishment of ‘standard’ Latin writing. If we look beside the finished forms of the Roman letters that we know so well, we can find relics of previous stages of the alphabet.

These survivals are a way to appreciate the Latin’s script membership of a wider family tree of writing. This article is about three such relics in Classical Latin writing, and the sense that they convey of alphabets that could have been.

1: C is for Gaius

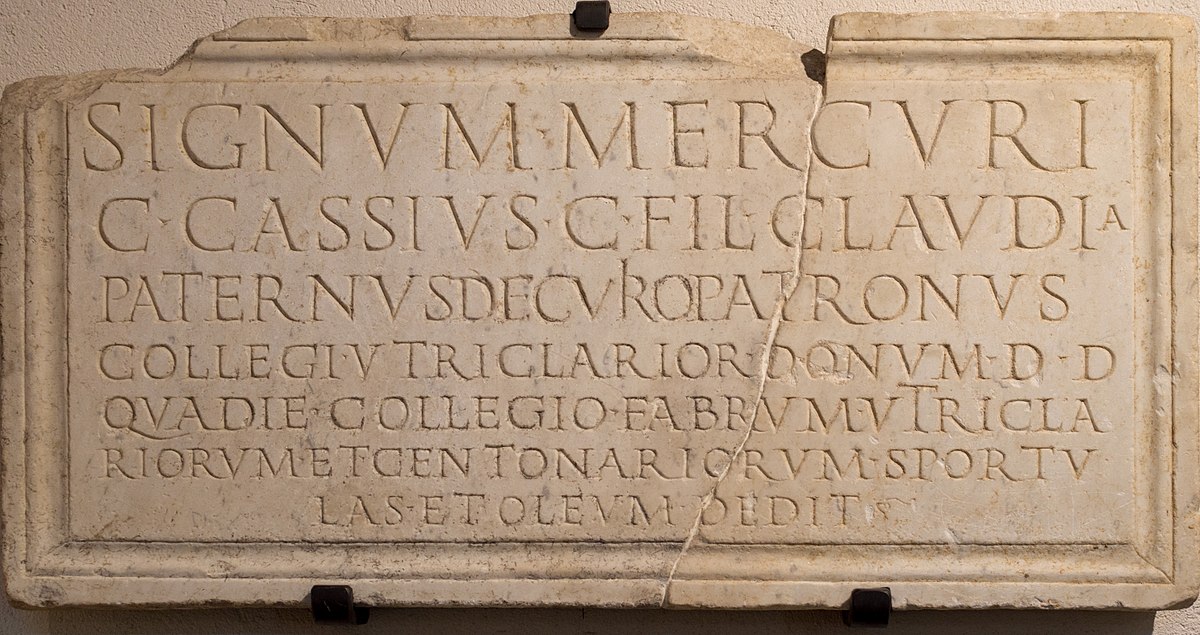

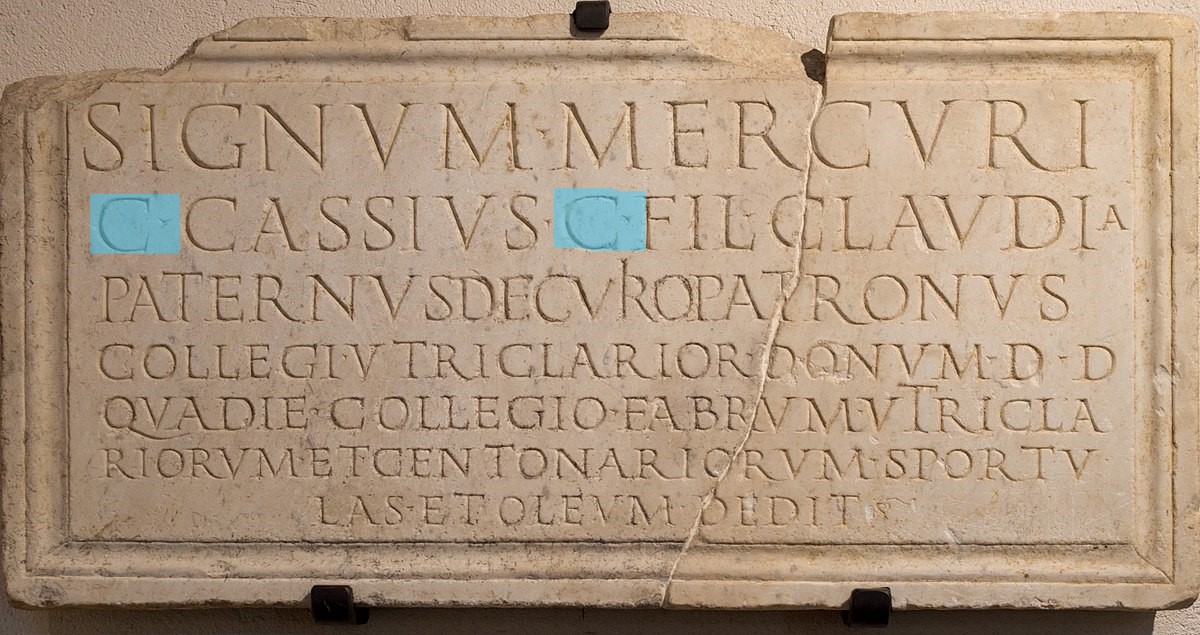

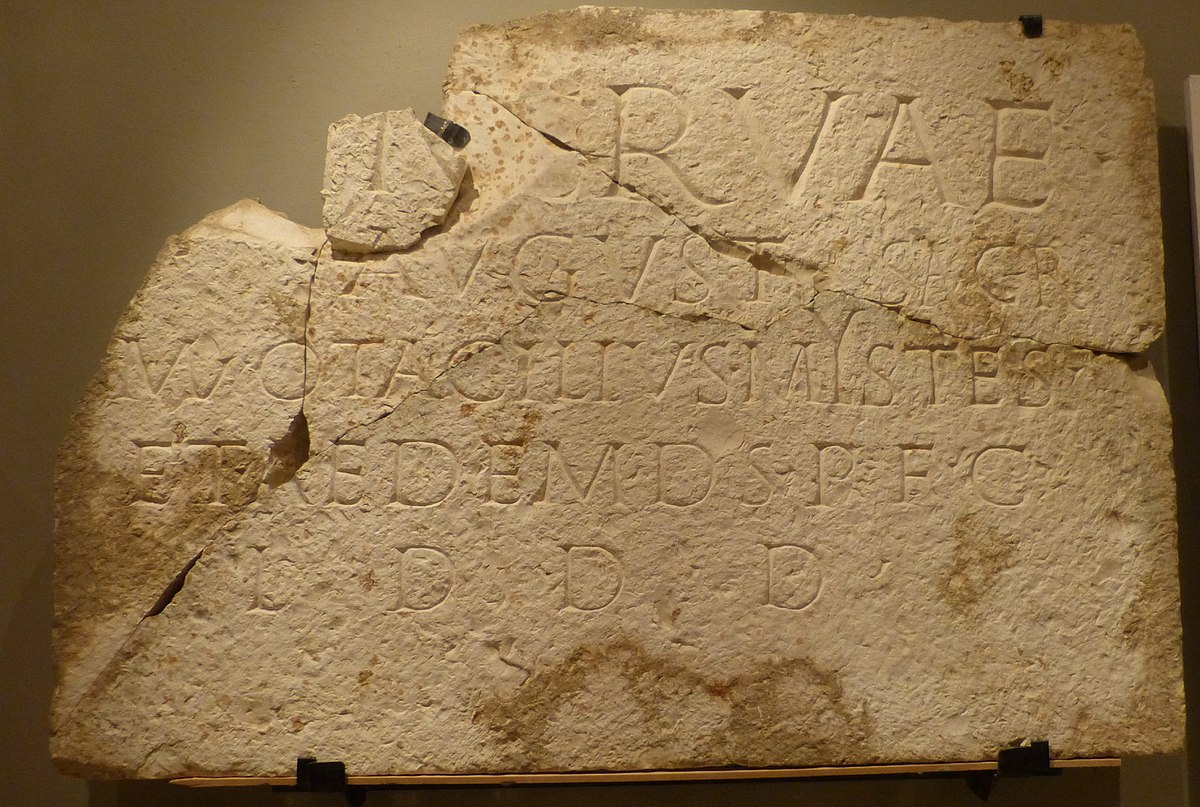

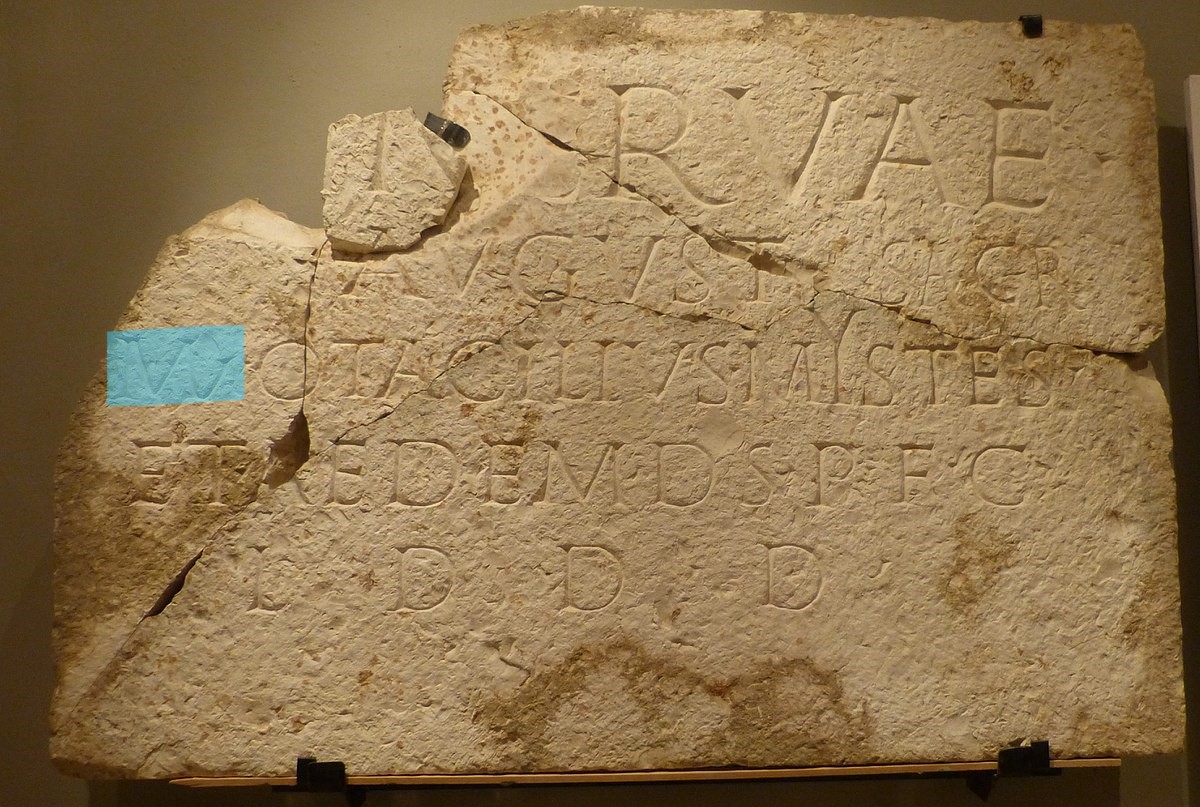

Around the turn of the second and third centuries AD, a sculpture of the god Mercury was put in Cemenelum, today part of the French city of Nice. Its sponsor, who celebrated his generosity in an accompanying inscription, was one Gaius Cassius, son of Gaius, of the Claudia tribe.

His name and his father’s are given in the text’s second line, but note how the personal name Gaius is abbreviated not as G, but as C.

The use of C as the standard abbreviation for the common name Gaius is a product of an earlier time before the invention of the letter G. At an early stage in Latin literacy, the letter C was used for both the voiceless sound /k/ (as in coat) and the voiced sound /g/ (as in goat, and also Gaius).

The voiced value was in fact the older use for C. This derived from the letter’s earlier history as the Greek letter gamma (Γ), and before that as the Phoenician letter giml (𐤂). Even the Phoenicians themselves were only stopping point in the letter’s long history, as it was passed through different hands on a roughly anti-clockwise route around the Mediterranean that began in the Kingdom of Egypt.

The function of C as a voiceless /k/ was a later legacy of the Etruscans. The specific sounds of their language led them to repurpose C for the voiceless consonant instead, and their pre-Roman prestige gave them considerable influence over how early Italian writers used the alphabet. So it was that C came to be reassigned to /k/. After a millennium of representing a voiced sound, the Etruscans switched the points and sent the letter C off on a different phonetic track.

For the Romans, the Greco-Etruscan dual-functionality of C then left them in need of a separate letter to distinguish between /g/ and /k/, since these were two distinct sounds in their spoken Latin language. The creation of G out of C was historically attributed to one Spurius Carvilius Ruga, a teacher in the third century BC. Whether he outright invented it or only popularised it, the new letter caught on.

G appears three times in Gaius Cassius’s dedication, along with the two relics from the time before it was born. Clearly, the use of C for Gaius was too well established to be bothered by the new character on the block. We see the same relic of old orthography in the abbrevation for the male name Gnaeus – namely, CN.

2: Per kalendar month

Leading on from the first relic, the Etruscan reassignment of C to the sound /k/ meant that there was now a surplus of letters in the alphabet – C now stood for the same sound as K. They were joined in that function by Q, although the three letters went back to Phoenician forebears (giml, kap and qōp) that represented distinct sounds.

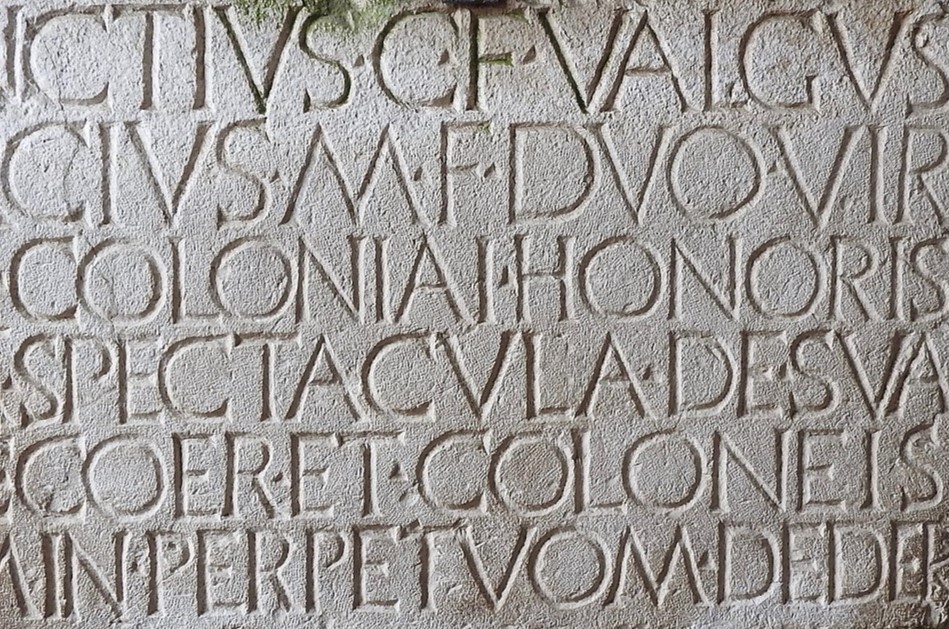

As the Romans took a better hold of the alphabet and trimmed off any excesses, C, K and Q found themselves a risk of removal. Q was saved by its use in the digraph QU (or rather, QV), while for all their other /k/ consonant needs, the Romans sided with C. From now on, Latin would have a C-full spelling, as in cantus, centum, circus, cohors and cubiculum. The Romans purged K from their writing. Only in a couple of corners of Classical Latin did the letter endure.

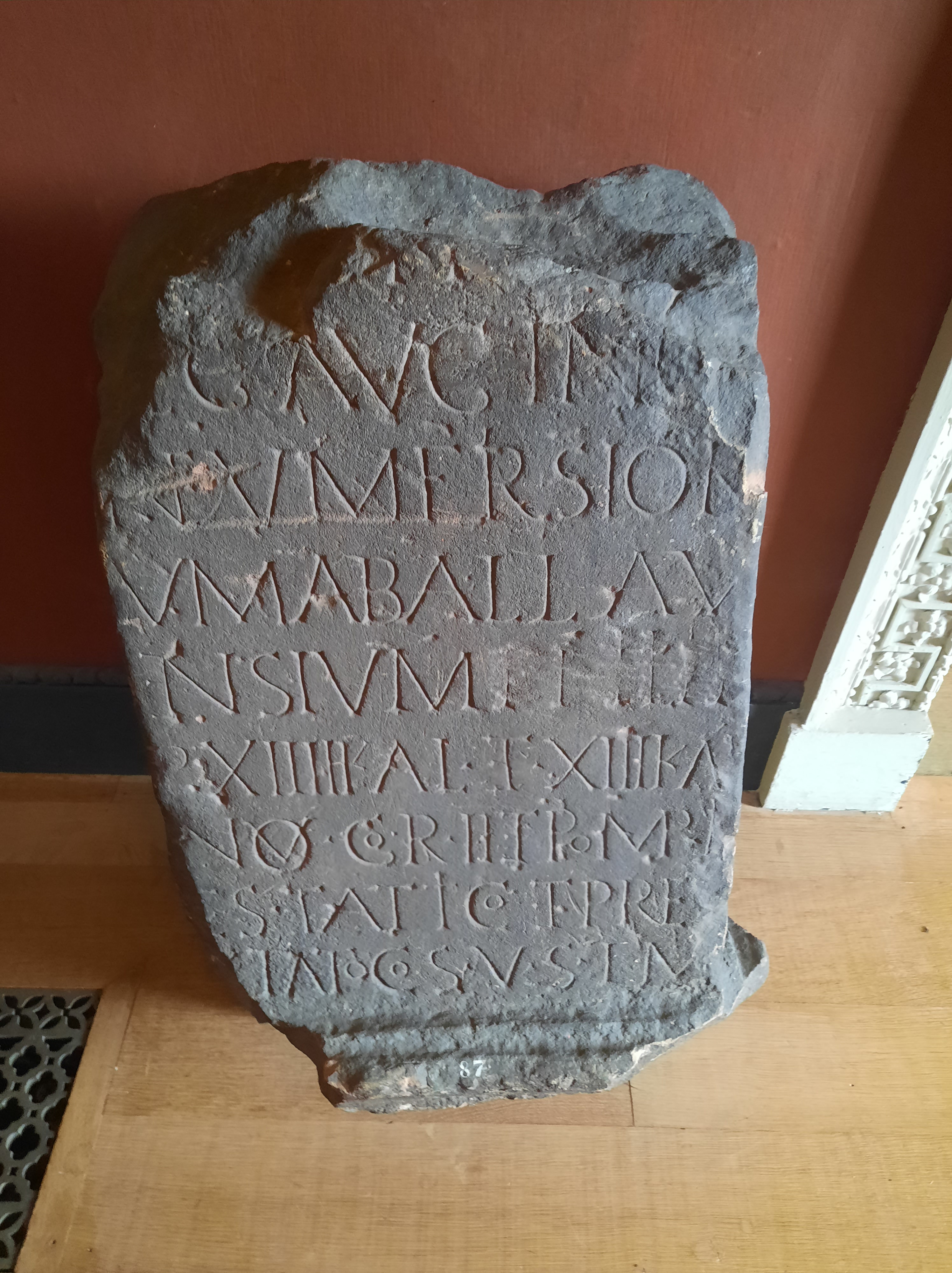

One can be found in the Romans’ year. In both inscriptions and literature, we find the first day of the month in the Roman system, called the calends in English, consistently written as Kalendae with a K. This key point of the month is of course the origin of the word calendar.

"Meministīne mē ante diem XII Kalendās Novembris dīcere in senātū fore in armīs certō diē, quī diēs futūrus esset ante diem VI Kal. Novembris, C. Mānlium, audāciae satellitem atque administrum tuae?"‘Do you not remember that I, twelve days before the calends of November, said in the senate that C. Manlius, the attendant and assistant of your audacity, would be openly in arms on a certain day, which was to be six days before the November calends?’

~ Cicero, Against Cataline 1.7

To save space and energy, we often find Kalendae abbreviated to Kal or simply K.

It may have been because of this handy abbrevation in dates that the K in Kalendae survived, or alternatively because it gave the word a certain air of antiquity. The calends were part of an ancient system, and the letter K, otherwise so avoided by modern Roman writing, may have conveyed a link to the early days of Rome.

3: Make a Manius out of you

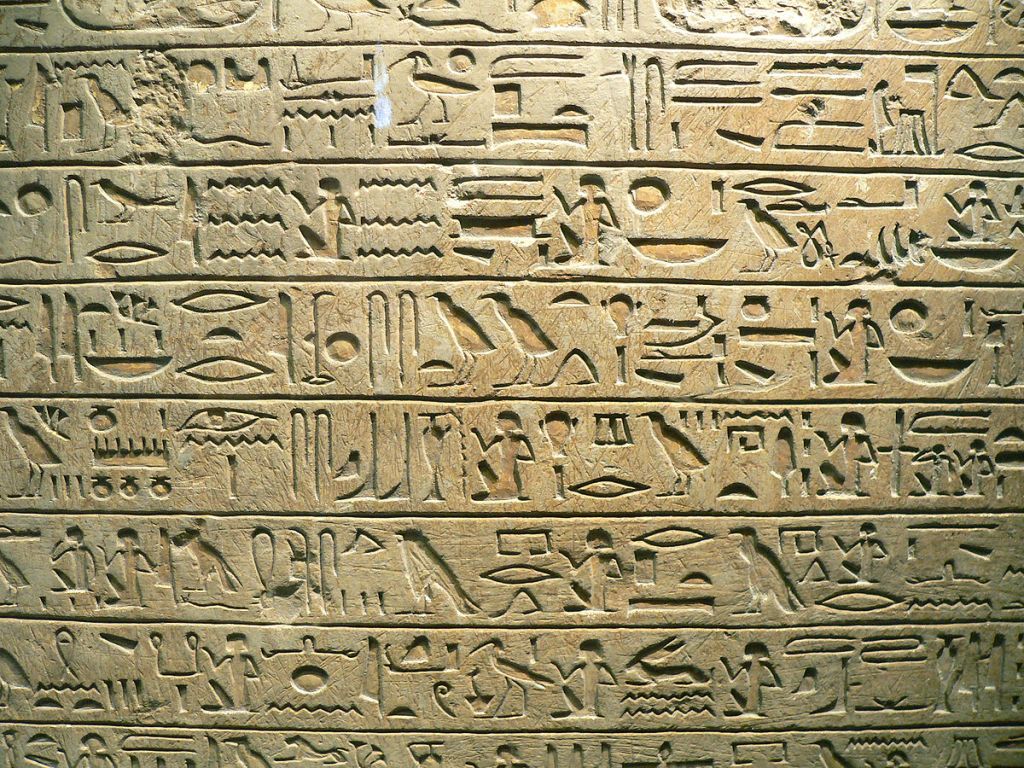

The third and final relic harkens back to the waters of the Nile. Egyptian hieroglyphs included a character that was intended to represent rippling water:

Write this three times and you have the Egyptian word for ‘water’, mw.

In the new system that would become our alphabet, that watery wiggle was assigned to the sound /m/, as in money. It was gradually shortened, losing many of its undulations by the time it had turned into the Phoenician letter 𐤌 (mem).

This, if you haven’t guessed, is the back story of our letter M. Both the Greeks and Romans eventually settled on the four-stroke shape of M that we know and love, but many archaic texts from Italy and Greece display a five-stroke version that nods to the letter’s longer form in earlier writing.

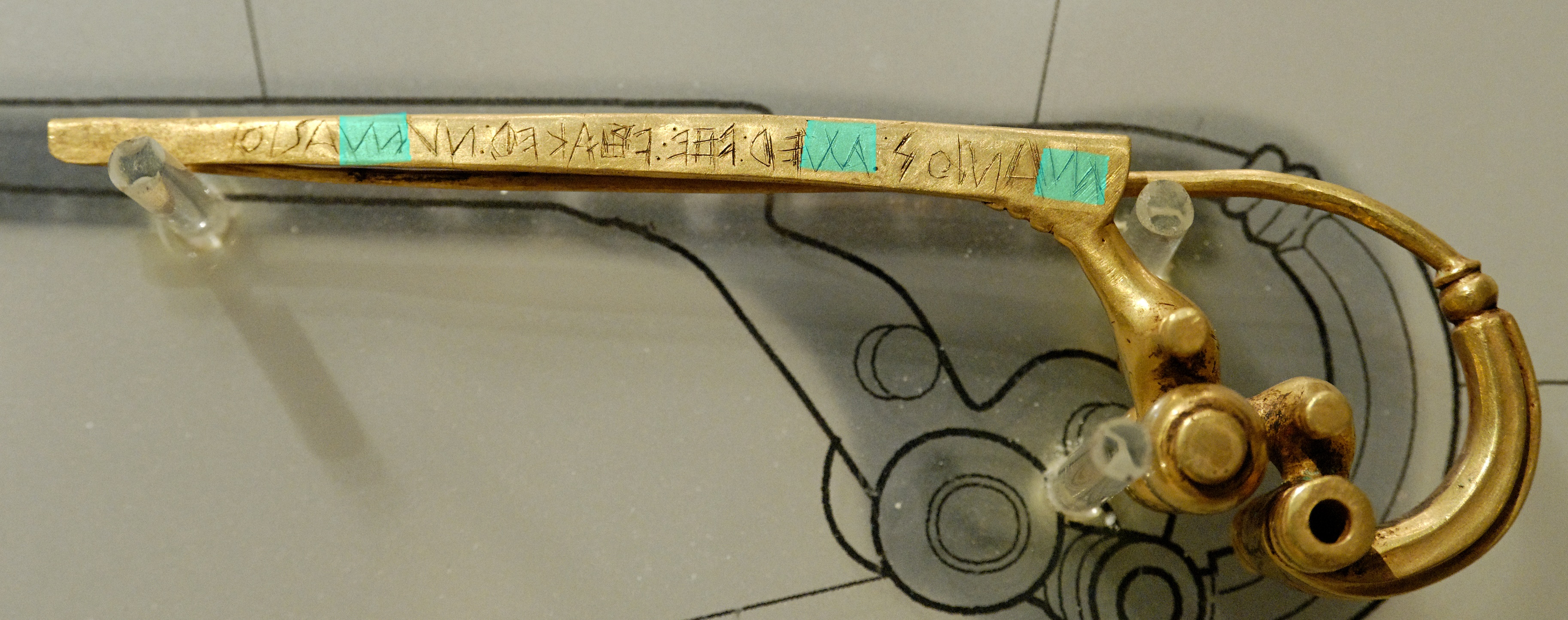

This five-stroke M is even preserved in some Classical Latin sources, specifically as an abbrevation for the male name Mānius.

It may take the form of an extra-legged W.

Alternatively, it may resemble a regular M with a final upward flick.

This special M remained an archaism from an earlier stage of the alphabet, like the use of C for Gaius, but it may have also taken on a new life as a handy abbrevation, like the use of K for Kalendae.

Very fittingly, both the five-stroke M and the name Mānius are the first letter and word in (debatably) the oldest text in Latin: the inscription on the Praeneste fibula, dated to the seventh century BC, which commemorates ‘Manios’ making the brooch for ‘Numasios’.

In these three ghosts that haunt Roman writing, we can get a sense of the long journey that our alphabet has been on. Its route had several twists and turns, each one contributing something to the shape and function of individual letters.

Without the Etruscans, we might still use the letter C for /g/, as the Greeks still do with their Γ. Without the Etruscans and the Romans’ ruling against redundant letters, we might spell plenty of C-words with a K instead. In the development of our letters, nothing has been inevitable, and everything has dependent on the linguistic and social circumstances of the day.

END.

References

- Hamilton, G. J. (2024). The origins of the West Semitic alphabet in Egyptian scripts (Vol. 40). Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Wallace, R. (2011). The Latin alphabet and orthography. A Companion to the Latin Language. 7-28. Wiley-Blackwell.

All images taken from Wikimedia Commons.

This is your best yet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Love the extra-manly ꟿ.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was very happy to stumble on this as I prepare a lecture on the evolution of the lowercase ‘g’ for a Typography3 class. (Was looking for an example of the Caius/Gaius bit after reading about it – I think in Hutchinson’s “Letters”). I’ll be showing your site to my students 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person