Reading time: 10 minutes

For this November’s post, I’d like to shine a syntactic spotlight on an unusual feature of English word order.

While you might not know it from my online offerings, I am first and foremost a syntactician: words are fascinating, but it’s how we arrange them together that interests me most. The linguistic field of syntax is, crudely put, the study of word order in languages; the field of historical syntax, my intellectual home, is the study of old word order, and how word order changes. I’ve devoted a sizeable chunk of my life to studying old syntax across a variety of languages. Yet amidst all that, I’d never noticed an uncommon feature of my native English until George Walkden casually commented on it at a conference this summer.

It’s all about questions. Or is it?

Questions and English: The Essentials

To receive information or confirmation from another person, we humans ask each other questions. To distinguish them from other uses of language (stating facts, giving orders, etc.), questions have certain linguistic properties. Clauses that serve an interrogative purpose can be divided into two general types:

- Wh-questions

These questions include wh-words (what, who, when, etc.), which imply something of the kind of information that is desired.

e.g. Who are you? What are you on about? Why am I reading this? - Polar questions

These do not contain a wh-word, and instead expect a simple ‘yes/no’ response that confirms or denies a proposition.

e.g. Do I have to keep reading? Is there is a point to all this?

We build questions with distinct interrogative qualities; one is intontation. I imagine that, even in your head, you read the examples above with a pitch that got higher at the end. That rising intonation will also be present when you read the final word of this current sentence, right? This prosody contrasts with the falling intonation that is typical of non-interrogative statements of fact. Compare the intonation of these two clauses:

- You’re leaving today.

- You’re leaving today?

Yet this distinct prosody is accompanied in English by a distinct word order. For wh-questions, we tend to put the wh-word first in its clause, regardless of what type of word it is. In English, a verb precedes its object in clauses that state facts. Yet this is not the case in questions:

- The linguist writes the text.

Order: Subject > Verb > Object - What does the linguist write?

Order: Object > Auxiliary Verb > Subject > Main Verb

This fronting of wh-words is widely known as wh-movement, understanding such orders to involve ‘movement’ from a more basic arrangement. As a word-order phenomenon, it’s extremely common, near universal, across the Indo-European family to which English belongs.

What though about the second type, polar questions? While these do not include wh-words, they likewise show a distinct word order, in that they begin with a verb.

- Does this make sense so far?

- Are these examples funny at all?

- Have you got the point yet?

- Can you see where this post is going?

We can think of this apparent inversion of the non-interrogative order as a similiar case of ‘movement’, in which the verb moves to an abstract position where it can convey the interrogative type of its clause. In my work, I understand this abstract slot to be the same as the one occupied by markers of subordination, like that, because, while, since and whether. These likewise communicate something about the nature of their clause. Modern English is quite limited in what verbs can be moved to this initial position; it’s really just functional verbs like have, be, do, can, will, etc. It’s noteworthy that have can really only show this order when it’s the functional auxiliary verb have, not the verb of possession have.

- Have you written the letter?

(Fine) - Have you the letter?

(Weird)

In older stages of English though, any verb could in principle occupy that position and create a polar question.

- “Hear’st thou of them? / Aye, my good lord.”

(Shakespeare, Macbeth 5.3) - “Fareth every knyght thus with his wyf as ye?“

(Chaucer, Wife of Bath’s Tale 1088) - “Wāst þū hwæt mon sīe?“

(‘Know you what a man may be?’. Anon., OE Boethius 34)

The thing is, this use of word order to build polar questions is pretty unusual. Globally so.

Interrogatives Inter-linguistically

To get a sense of how common this syntactic means of asking polar questions is, we should consult WALS. The World Atlas of Language Structures is an incredible resource, compiled by expert typologists, and it’s an easy way to waste time linguistically.

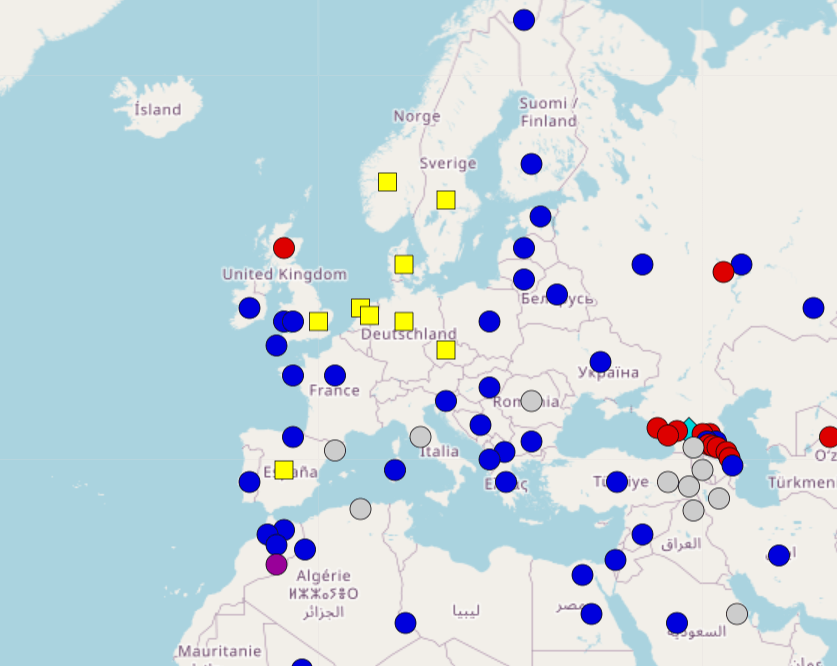

Feature 116A: Polar Questions offers this map for the present-day, spoken languages of the world:

Red: Interrogative verb morphology

Grey: Interrogative intonation only

Yellow: Interrogative word order

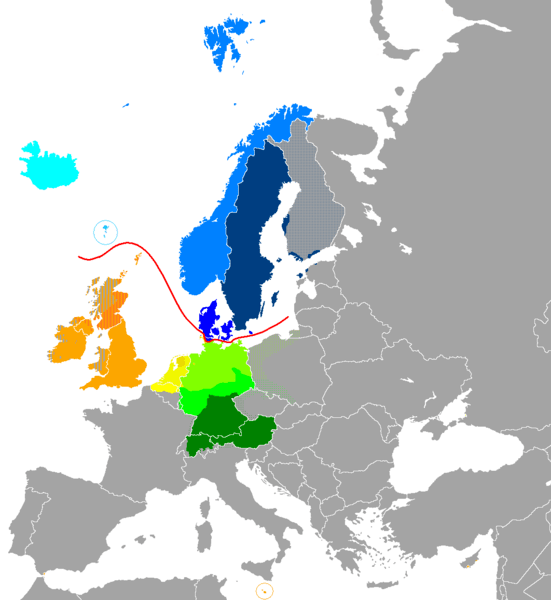

We see here that using word order for polar questions, in yellow, is pretty limited. It’s clearly a commonality of the Germanic languages, such as German, Dutch and Swedish.

The following questions translate does the man see the car? in those Germanic languages, with the main verb put first.

- Sieht der Mann das Auto?

(German) - Ziet de man de auto?

(Dutch) - Ser mannen bilen?

(Swedish)

As the map shows, other languages of Europe use this word order; for some, it may be due to Germanic influence. Czech, a language in prolonged contact with German, notably has it too, in contrast with most other Slavic languages. The map does not include historical languages, nor languages for which verb-first order is an alternative option, such as French.

- Parles-tu français?

(French) - Voit-il la voiture?

(French)

This arrangement is formal though, limited to certain registers in French today. French is instead listed on the map as a language with a question particle, namely the formally phrasal est-ce que /ɛskə/. Such particles are typical in languages like Polish (czy) and Irish (an), in combination with intonation.

- Czy mężczyzna widzi samochód?

(Polish) - An bhfeiceann an fear an carr?

(Irish)

It’s intonation alone that serves to form polar questions in Italian, for one.

- L’uomo vede la macchina.

(Italian statement) - L’uomo vede la macchina?

(Italian question)

We should bear in mind though that languages are complicated, more so than this map can convey. One language may combine a variety of available methods to distinguish a question from a statement, including distinct word-order patterns. Yet, for the purposes of this piece, the fact remains that the Germanic languages’ strategy of placing of the verb first (coupled with question intonation) is typologically unusual and a unifying feature of the Germanic family.

But Why?

All this naturally prompts the question of why Germanic languages do this. In terms of the order’s origins, this is a question for historical linguists, like me. I do have a working explanation; it is, in brief, that this word order is a useful accident.

We find in most historical Germanic languages (e.g. Old English, Old Norse, Old High German) that they are fussy about where the verb stands. In main clauses, whether they be a statement, question or order, the verb has an early position. In Old English, for instance, we generally find that the verb is the first, second or third constituent of the clause. The same orders in Modern English would sound strange, poetic or just ungrammatical.

- “Cōmon hī of þrīm folcum“

(‘Came they from three peoples’. Bede’s History 1) - “On þysum ilcan ġēare hēt se cyng…”

(‘In that same year ordered the king…’. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 993.) - “Þǣr hire brohte Godes enġel swylċne ġerelan“

(‘There to her brought God’s angel such a robe’. Martyrology 9.)

What we see is that the verb consistently occupies an early position, regardless of the type of clause. Optional material of a topical quality may or may not precede it. With the exception of Gothic, a rule seems to have developed in early Germanic that limited the position of verbs in main clauses. This syntactic behaviour is still common across the Germanic languages today, as in Modern German’s Verb Second rule. This generic verb-early order is something that English gradually lost over the Middle English period, but it endures today in certain contexts. These include wh-questions (in which it really isn’t needed; the wh-word alone would suffice) and initial negatives.

- What do you want?

(Fine) - *What you do want? / What you want?

(Weird) - Not only is it good…

(Fine) - *Not only it is good…

(Weird)

The use of word order in polar questions is another survivor of the old verb-early rule, one that I think has survived simply because it is useful! While this order may not have first arisen with the specific purpose of forming questions, but rather as part of a general rule of verb placement, it has outlived that rule – because now it does help us to form polar questions. It’s a useful relic of a lost grammar.

So, that’s it for my November syntactic safari. I hope this has been a captivating and comprehensible survey of a bit of word order that we take for granted. For me at least, it’s enjoyable to get to know my native English better and in its wider context. I reckon it’ll make you, dear reader, think twice in future about the word order of your questions, won’t it?

END.

References and Further Reading

- Dryer, M. S. (2013). Polar Questions. In: Dryer, M. S. & Haspelmath, M. (eds.) WALS Online (v2020.3) [Data set]. Zenodo.

- Eckardt, R., & Walkden, G. (2022). A particle-like use of hwæþer. Discourse Particles. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Walkden, G. (2014). Syntactic reconstruction and Proto-Germanic. Oxford University Press.

Cover image from here.

Speaking of WALS: I took a look at what it says about the languages I know. And as so often, WALS more or less misrepresents Uralic.

Finnish does have a question particle (-ko/-kö), which is actually a clitic and attached to the focused word: Ostiko Liisa auton? (‘Did Lisa buy a car?) / Liisako auton osti? (‘Was it Lisa who bought the car?) / Autonko Liisa osti? (‘Was it a car that Lisa bought?’). AND this focused word MUST be sentence-initial, so Finnish question marking is very much about word order. Same goes for North Saami.

Estonian has a free-standing question particle (kas), but at least in some cases there is also the option of using a very Germanic-looking word order model.

Hungarian has a question particle/clitic (-e), but it is mainly used in subordinate questions, in direct questions it sounds archaic or dialectal. The normal way of marking polar questions in Hungarian is a peculiar rising-falling intonation. (For whoever is interested: Beáta Gyuris has recently been doing research on polar negation in Hungarian.)

For Mansi, WALS claims (with reference to an obscure grammar more or less unknown to the Finno-Ugristic world, but hey, it has appeared in English in America…) that it uses a mixture of two strategies: question particle or “interrogative verb morphology”. I have no idea what this is supposed to mean. Generally, (North) Mansi works like Hungarian, i.e. uses a question intonation, but the question word ‘what’ can also be used.

Of course, you might claim – as typologists sometimes do – that this is a marginal issue, or even that typologists have a way of looking at languages and seeing what linguists working with just one language or language family cannot see. However, I’d rather say that things like this happen when typologists read bad grammars and misunderstand them. And especially when the questions for which the answers are sought have been poorly formulated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you not on Threads?

LikeLike

Me? No, I’m not, but perhaps I should be?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have left Twitter for all the obvious reasons, but the linguists seem to linger there instead of moving to Threads or BlueSky. Also looking for Irish content, but that’s not your problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In MnE verb second order isn’t restricted to initial negatives (as well as Wh-? questions), but is also used after temporal and spatial restrictions (though more usually in writing, perhaps): ‘Only then can you …’/’In the corner sat a …’ .PS ‘Have you the letter?’ may sound weird (though not to everyone, I suspect), but ‘Have you any idea ..? (etc.) sounds quite normal.

LikeLike

Did I say that it was restricted to those first two contexts?

LikeLike

My intention was merely to point out that in this context initial negatives have the effect in question because they are (admittedly a full-on) part of the category ‘restricitve’, but with hindsight I could have been less ambiguous. I have since wondered whether you would include imperatives (by analogy with polar questions): these can be also be avoided by intonation – ‘You go and see him, then, and I’ll …’ And what about subjunctives (obviously in formal language): ‘Had I known’, ‘Were that so’, ‘Should he refuse’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are some other unusual word orders which seem to have some lack of certainty 0r even wishful thinking) in common: ‘Be that as it may … ‘/, ‘Long live …’ / ‘May you never …” And what about ‘Suffice it to say…,’ ‘Woe betide …’ (though I suppose the latter is just the subjunctive used as a 3rd person imperative).

LikeLike

“Have you the letter?” would be weird in American English, but my understanding is it wouldn’t be that weird in British English.

LikeLike

Spanish is very consistent about inverting the position of the subject and verb to form a question, putting the verb at the beginning. This is highly consistent across all verbs and all registers. Worth mentioning as a counter example to Romance languages that do not do this. (I speak Spanish as a second language, so it’s possible there are exceptions I’m unaware of)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting analysis! I’d like to add two American observations about variations in English question formation:

1. The example *“Have you the letter?” has a structure that Americans perceive to be uniquely British. In fact, I have often heard Americans who want to briefly sound British for some humorous reason use this specific pattern of fronting ‘have’ when it is a verb of possession. However, it would only be with an indefinite article or other indefiniteness marker, “Have you a match?” being the most commonly used question. (More narrowly, it’s a satirical comment about register, of course.)

2. The complete omission of the auxiliary as the fronted element of the verb in a question, as in *”What you want?” is a typical feature of African-American English. It carries across other contexts: What he say? Where Fred go? As a result, the verb isn’t fronted at all. This is the same in polar questions. The auxiliary is omitted, or in the case of do-insertion not inserted, thus making all non wh-questions intonation-dependent: Fred go home?

(Note: Although we Americans have in most cases replaced African-American with Black since it is more inclusive, I’m referring to a usage pattern of a specific group, so I used the prior term. I hasten to add that my African-American students and colleagues are excellent code or register switchers.)

LikeLiked by 1 person