Reading time: 10 minutes

Now, I must confess, I have been somewhat preoccupied for the past two months, and so haven’t dedicated time to this site. The jump into the world of podcasting has taken a lot of effort, and yet the website hasn’t been far from my thoughts. So, for this October, I’m getting back to my online roots and geeking out about historical linguistics and cool medieval texts. Here’s my introduction to one such text.

What are the Reichenau Glosses and Why Should I Care?

It’s fair to say that the Reichenau Glossary isn’t the best known historical document. Yet it deserves its moment in the spotlight, being of great interest and importance in tracing the history of the Romance languages. This modern-day language family (including French, Italian, Spanish, Catalan and Romanian) emerged out of Latin, which the Romans had spread across Europe through their conquests. There’s really no hard line though to say when Latin ended and Romance began, a tricky issue that I got to explore recently with medieval expert Charley Roe on the podcast. This is not only because our sources for early Romance are scarce, but also because language change is slow and gradual, barely perceptible when you are living through it. There are no clean breaks between generations of language users to which we could easily add our labels.

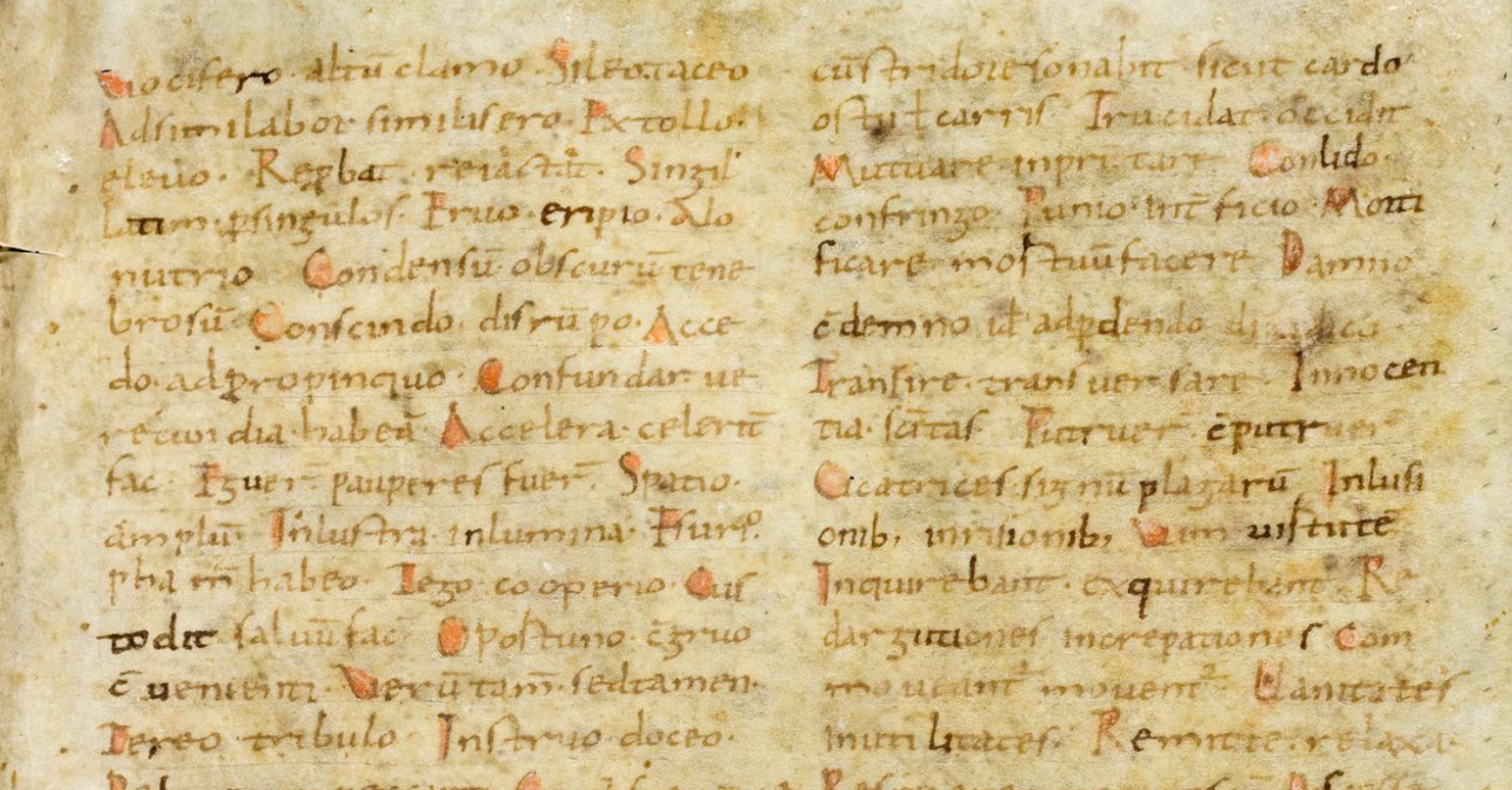

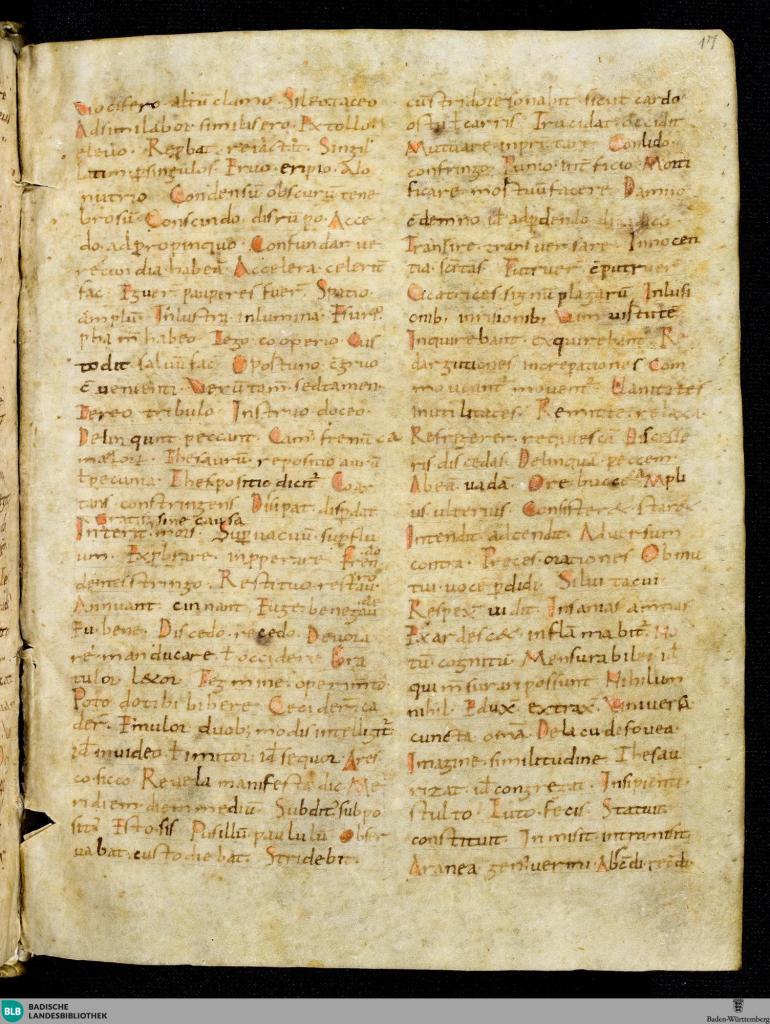

The Reichenau Glossary is one text though that tells us a great deal about when certain features of the Romance languages had arisen, and how far the Late Latin language had diverged from its older, classical standard by the time it was composed. As the name suggests, it’s several long lists of words, compiled in the 8th century AD, and found in 1863 among the library of the German abbey of Reichenau. The glosses are principally written in the manuscript Karlsruhe 115, housed today in the Badische Landesbibliothek. The language of the text is Latin, and the purpose of the glosses is to explain and provide synonyms for words used in St Jerome’s 4th/5th-century Latin translation of the Bible, known as the Vulgate. One part goes through tricky words in the Bible book by book, another part glosses words alphabetically.

Based on the vocabulary used, we can say it was originally created for scholars in what is now northern France, specifically at the abbey of Corbie. The language of that region would have been something very Latin-like, and people would have thought of it still as the lingua Romana. Yet the fact that the glossary was written implies that some readers of the Vulgate were having difficulty in understanding the language of Jerome from three centuries earlier. Many shifts in vocabulary had occurred since then, altering the meaning of some words, while others had been lost from everyday speech and replaced by new vocabulary.

In the glosses given, we see first or very early appearances of words and meanings that are still common in French today. It’s not accurate to say that the language of the people reading the glosses was recognisably or distinctly French yet, but it was heading in that direction. In the Reichenau Glosses and the lexical shifts that necessitated them, we can witness the slow birth of French.

“From the multitude of words that were deemed difficult for eighth-century readers, one can see how much the lexicon had changed in the intervening centuries. The words given as glosses were generally those destined to survive in Romance.”

Alkire & Rosen 2010: 319

Let’s dive into some of those words to see how.

Late Latin and Future French: Examples!

Here are fifteen examples, with my explanations, of what the Reichenau Glosses look like. For each, we first have the word used in the more classical language of Jerome’s Bible, followed by a synonym that users of the glossary would have better understood. For a longer list, with brief notes, have a look here.

ager ~ campus

‘field’

While Jerome uses the Latin word ager for ‘field’ (hence English agriculture), it’s here glossed as campus. The latter is a well-documented word in our classical sources, but its usual meaning is of a large, flat area, not necessarily one cultivated for farming. By the time of the glosses though, campus had clearly taken over the agricultural sense of ager, which it still has today in French champ.

liberos ~ infantes

‘children’

Liberi is a common classical term for ‘children’, specifically used in the plural. Infantes meanwhile were very young children, of the non-speaking (in–fans) age. Yet infantes broadened in its meaning, coming to refer to children in general, as in French enfants.

arena ~ sabulonem

‘sand’

It’s true, an arena was originally just a lot of sand. The glosses reveal that in Late Latin, it was losing ground to sabulo, once a rougher kind of sand, or gravel. The latter is behind the usual words for ‘sand’ in French and Italian today, sable and sabbia.

caseum ~ formaticum

‘cheese’

English is like Spanish, in that the words for ‘cheese’ (cheese and queso) go back to Latin caseus. Yet French’s word, fromage, is the result of a new formulation, once referring to the mould (forma) in which cheeses were made. This gloss is one of those that help to pinpoint the document’s Gallic origins.

ore ~ bucce

‘mouth’

Classical Latin mainly used os for ‘mouth’ (hence English oral), while bucca meant ‘cheek’. Perhaps through casual, colloquial use, bucca was destined to take over from os. This gave rise to words in Romance today like Spanish boca, Italian bocca and French bouche.

rerum ~ causarum

‘things’

The useful Latin word res is the source of English words like real and republic (the ‘public matter’). Yet the root noun itself lost out to causa as the Romance word for ‘thing’, as in Italian cosa or French chose.

pulcra ~ bella

‘beautiful’

While classical authors might have called a beautiful thing pulcher, in the glosses we witness the revival of the adjective bellus, responsible for French beau and Italian bello.

optimos ~ meliores

‘best’

The glosses also give us glimpses of grammatical restructuring. Like how English has good/better/best, Classical Latin has bonus/melior/optimus with three distinct words to express the three degrees. What we see here though is that melior, originally only ‘better’, is taking over from the superlative optimus. This anticipates the situation in French today, in which meilleur is both ‘better’ and ‘best’. What differs now is whether the definite article is used too (‘best’ is le meilleur).

saniore ~ plus sano

‘healthier’

Likewise, this gloss hints that the comparative form of adjectives is switching from being expressed through an ending (-ior) to being expressed through a separate word (plus). This is still how French tends to form comparatives, as in plus petit ‘smaller’ or plus sage ‘wiser’.

edunt ~ manducant

‘they eat’

Manger is well known as the verb for ‘to eat’ in French today, and here we see how it took over from edere. The latter is part of a large word family, including English eat, but it was usurped by manducare, originally ‘to chew’. This verbal root is why the body part that is tasked with chewing is your mandible.

abio ~ vado

‘I go’

This is another case of a core verb being replaced. Abire ‘to depart, to go’ builds on the verb ire. This is still a part of French today (e.g. j’irai ‘I will go’), but it’s been joined in the overall conjugation of the verb aller ‘to go’ by other roots. This is known as suppletion. So, while Latin ire has given French the future-tense form j’irai, Latin vado is the source of present-tense je vais.

adversum ~ contra

‘against, opposite’

Prepositons were changing too! It seems that adversus (literally ‘turned-to’) had become unfamiliar, with contra assuming its functions, as contre does in French today.

semel ~ una vice

‘once’

It’s not just single words that the Reichenau Glossary gives us infomation about; some phrases have their earliest appearances in it. While Cicero and Jerome might have said semel for ‘once’, the readers of the glosses were instead used to the phrase una vice, just as the French today say une fois.

singulariter ~ solamente

‘only’

This is an early attestation of a very Romance construction: forming adverbs with -mente/-ment. This is the typical means of doing so in French today (e.g. heureusement ‘happily, facilement ‘easily’, étrangement ‘strangely’, seulement ‘only’, etc.). It’s an ending today, but -mente/-ment was actually once a noun and a separate word. It comes from Latin mens ‘mind’, as in English mental. This noun fused with the adjectives that used to modify it, creating a new class of adverbs. For instance, to do something clara mente ‘with a clear mind’ came to mean simply ‘clearly’.

Gallia ~ Frantia

‘France’

And to end, a real sign of how much things had changed: thanks to the Franks, Gaul had become France!

This is only a smattering of the many words that the Reichenau Glossary includes. There’s lots more that I could get into, such as the everyday words of Germanic origin that are included and therefore must have entered the local language. I hope at least that these fifteen examples are enough to demonstrate why a load of eighth-century glosses are of such interest and value for historical linguistics. The language of the document is arguably still Latin, not yet French or some other Romance language, but it’s a fascinating witness to the gradual change from one to the other. Out of these countless individual shifts in vocabulary and grammar within the language of post-Roman France, something that we can call French would eventually be born.

END.

References

- Alkire, T., & Rosen, C. (2010). Romance languages: A historical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Badische Landesbibliothek.

- Engels, J. (1968). Les” Gloses de Reichenau” rééditées. Neophilologus, 52(4), 378.

- Quirós, M. A. (1986). Las glosas de Reichenau. Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica, 12(1). 43-50.

- Orbis Latinus