“… Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken.”

(William Shakespeare, Sonnet 116)

February 14th has come round again, and love is in the air!

‘It was different in my day,’ older souls may grumble, thinking fondly back to when relationships were courtships and dating was wooing. Before that day, we imagine dark days of marriage by command and affection as an optional extra. After that day, we now find a romantically frustrated youth, often ghosted and getting by on hook-ups.

There’s an argument to be made that love is fickle, a passing fad that has had its moment in the cultural sun. ‘Love is dead, long live lust!’ Now dawns a day of transactional pragmatism and selfish desire. Love’s blossom blown away, the cynic will assign the word to the simulacra of red hearts, roses and soppy sayings required to sell more Valentine’s cards.

I disagree; I have more faith in love. Would you believe that that faith comes in part from etymology? If you know me, and how I call the romantic realm of historical linguistics home, perhaps you would.

I’ll let poets and historians battle it out over the exact nuances of old references, but I can at least say that there is constancy and a long history behind this word love of ours. When we investigate our words and their journey across time and space, we see how we are connected to linguistic ancestors (not necessarily biological ones). They may have lived thousands of years ago, but they apparently loved as we still do. If love can survive for so long, what can our times do to dislodge it from our hearts?

Seeking the word love in our records for the English language turns up a cornucopia of occurrences. It appears in surviving texts from the period of Old English, the language prior to the arrival of a linguistically significant army of Norman warriors in 1066 AD. The concept is recognisably our own, high in its emotional content and broad in its application.

Love is there, for example, in the ancient poem Beowulf, included among its monsters, manly heroes and mead halls. The poem speaks of good Queen Hygd, who “lufode ða leode” (‘loved the people’) she was dispensing drinks to in her hall. They surely loved her back. The title character Beowulf tells King Hygelac man to man that he would always “þinre modlufan maran tilian” (‘strive for more of your mind-love’). These were days of yore before the adoption of certain signs of modernity, namely the letter V. English writers back then made do with F.

Though its form has changed in sound and spelling over the centuries, the word love has clearly remained a core item of English vocabulary. It’s been accompanied by daughter words too, derived from it, like lovely and beloved, all of them full of warmth and affection. They may be undergoing a kind of weakening, as love muscles in on the territory of like. A kind of semantic inflation has meant that I love pizza has become a reasonable expression. This use of the word would’ve confused Shakespeare, along with the pizza. Nonetheless, love retains its rank as the supreme affection.

Love has sister words too, born from the same root, but some of these have fallen into obsolescence. Lief is an adjective meaning ‘dear’, which was commonly employed in Old English (Beowulf himself is twice affectionately called “Beowulf leofa”), but which has since retreated into archaic language. That said, lief limps on as the first part of the unusual word livelong – as in the livelong day. Originally, it was literally ‘the dear long day’, with lief brought in to add emphasis to the length. Throughout its employment, those who were lief to you were valued, treasured.

If we adjust our scope to consider geography as well as chronology, similar-looking instances of love appear in other languages. Over the North Sea from England lie the Netherlands and Germany, where people speak Dutch and German. An Amsterdamer would know his or her strong feelings for a compatriot as liefde in Dutch. Over the border in Germany, the same high attitude is known as Liebe, and a dear thing is lieb.

But how to explain these similarities? The linguistic archaeologist has three options. One is to put them down to simple coincidence. Another is to ascribe this to influence, as one language donates words to another. These are both unlikely scenarios. The words bear too many similarities and too many speakers in one corner of the world for this to be just luck. As for influence, love is such a fundamental feeling that it would be brave to argue that the English gave the word and its concept to the Germans and the Dutch, or one of those two to the English. Instead, the third option stands out as most plausible: that love, liefde and Liebe share a common ancestry, and are products of a time when English, German and Dutch were one language.

The three emerged from their common gradually, forming a linguistic family of relatives. This ‘Germanic’ family isn’t limited to the aforementioned three. When an Icelandic speaker calls a dear thing ljúfur and a Swede describes something lovely as ljuvlig, we have evidence to group their languages within Germanic too. These five and others trace descent from a common Germanic forefather, spoken in northern Europe from around the year 500 BC. But this language wasn’t written down in texts that we now can read. What we’ve done here is step off the edge of history, guided by language into prehistoric darkness.

Within that original language (Proto-Germanic), the ancestor of our love was a potent concept, just as it remains for us today. Within its purview, it contained not only romantic and sexual attraction between two people, but also tenderness, affection, desire, respect and goodwill. When Germanic speakers later encountered Christianity (which puts a high premium on love), it was with love and like words that its central, transcendental concepts were translated. Speakers and writers of Gothic, a deceased aunt of English, coined the compound term brōþralubōn (‘brother-love’) in the 4th century AD. This was a literal translation of the Greek word philadelphía, found in St Paul’s letter to the Romans, but now better known today as home to the Eagles and Phillies. No doubt the coming of Christ brought and fostered new perspectives on love, but it wasn’t an alien concept, unmatched by existing Germanic vocabulary.

We can still travel further back. Around the same time that Germanic speakers were living in northern Europe, the Romans were putting themselves about the Mediterranean. In their Latin language, we can spot a similar-looking word likewise used to express a positive disposition. This was lubet, meaning ‘it pleases’. It was how a republican-era Roman would translate our modern English word like. Plautus, a playwright penning his words around the year 200 BC, has the character Philematium flirtatiously quip “quod tibi lubet, idem mi lubet” (‘what you like, I like too’).

Lubet was an everyday verb for the Romans, and it shared its lub- core with lubido, a noun meaning ‘desire’ or ‘pleasure’. In the later classical language of Caesar and Cicero, lubido had shifted in one sound to become libido. This noun might have remained an antique, had it not been resurrected in the late 19th century, when leaders in the newfound field of psychoanalysis, chiefly Sigmund Freud, summoned libido to serve in their psycho-sexual analyses.

Bear that lub- root in mind, because we find it elsewhere in Europe. To declare fondness for something or someone in Polish, for instance, you’ll need the verb lubić. Bring out a phrase like lubię Polskę (‘I like Poland’) in Warsaw, and you’re sure to make friends. Polish is one of many Slavic languages found across Europe, and their familial connection is substantiated by very similar words. Just as Polish has lubić, Russian has ljubítʹ, Serbo-Croatian ljubiti, Slovak ľúbiť and Czech líbit – all to do with loving, liking, kissing and adjacent activities. Their co-existence points to a source word, which specifically meant ‘love’, in a prehistoric Slavic parent.

But again, how to explain these similarities? Latin and the Slavic languages are too distant to be included within the Germanic club, both linguistically and geographically. Latin emerged in Italy around the river Tiber, while the likely homeland of Slavic speakers lay in eastern Europe. Nonetheless, Latin and the two families share a significant amount of similar vocabulary, among L-words related to loving, pleasing and desiring among them.

Our scope has to expand even further, because words resembling love, lubet and lubić in appearance and meaning pop up in India too! Great compositions in Sanskrit, an ancient and prestigious language of India, include words built around the cores lubh– and lobh-. We find verbs like lúbhyati, meaning ‘to desire’. The negative consequences of these positive emotions are reflected too in such Sanskrit words; the Mahābhārata, the world’s longest epic poem, often warns against lobha (translatable as ‘greed’, ‘covetousness’ or ‘lust’). This was a secondary development, though; love and desire were primary.

One of these languages – from among Latin, Sanskrit, the Germanic group and the Slavic set – cannot subsume the others. Instead, they represent visible branches of a dense family tree, the common trunk of which is lost to time. Just as the immediate ancestor of the Germanic languages is a prehistoric hypothetical, so too is its own grandparent. But while Germanic alone took us only back to 500 BC, we now have the means to travel back perhaps as far as 4000 BC. That grandparent, located even further back in prehistory, would beget not only Latin, Sanskrit and our dear English, but a family that, before the modern era, was already strewn across Eurasia, from eastern India to western Europe. Hence, we know it as Indo-European.

Estimates vary as to when the single proto-ancestor of the Indo-European group was spoken, but six thousand years before the present day is a common suggestion. I appreciate that, to newcomers, this idea may feel like a flimsy construction, built on nothing but language. Yet the idea is a couple of centuries old and has stood the test of time. Countless words and bits of grammar have together built a steady platform for us to reach so far back. One of those words is love.

Six thousand years ago, give or take a century, somewhere out on the Eurasian Steppe (a large expanse of grassland), there were people who lived, died, ate, drank, hunted, farmed, fought, built and, more importantly, loved. Their words to do with loving would have built around a linguistic core. This, on the basis of what it became, was something like *leubʰ-. (That asterisk indicates that we cannot be sure, but this hypothetical form is what the evidence points us to.)

These people haven’t left us today much in terms of artefacts, but they did pass on their vocabulary. Handed down over millennia, their *leubʰ– words would eventually produce our word love, as well as our libido via the Romans. The collective linguistic evidence points to *leubʰ– giving expression to very high feelings; its descendant words are united in desire and delight.

The people out on the Steppe loved and spoke about their love, and now so do we. Their words and their concepts have endured countless societal shifts since, and it’s this etymology that gives me a degree of hope for the survival of love in the immediate future. We today, when we use the word love, are connected to ancient human affections, desires and passions via the very words we use. I personally think that that, for no want of a better word, is lovely.

END.

References

- Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache

- Kroonen, G. (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

- oed.com

Sources

- Beowulf

- Plautus’ Mostellaria

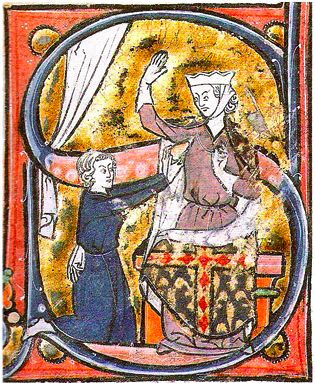

Cover image, from Wikimedia, of a 13th-century manuscript illustration from the Roman de la poire, in which a suitor offers a somewhat anatomically heart to his lady.

A witty and charming paen to love, loving, and being loved. Would “love” to understand how, historically, this differed linguistically from Greek eros, storge, philein, etc. perhaps next year.

LikeLiked by 1 person