In previous years, I’ve seized on the annual holiday of Christmas as inspiration for a December article. For this year, though, I fancy a foray into the weather conditions associated with that holiday: that is, the cold.

Christmas imagery is inseparable from low temperatures, what with all its snow, reindeer, and jolly gentlemen in fur-lined red jackets. This imagery finds its origins, of course, in the northern hemisphere, prior to the holiday’s exportation to the south of the globe. I always feel sorry for shopping-mall Santas suffering through an Argentine or Australian summer. For any meridional readers, then, take this article as a mental tonic, a vision of cooler days to come.

In particular, I want to climb into the family tree of the English word cold. It’s a piece of vocabulary with an ancient pedigree, and consequently some interesting connections too. It also offers an example of when the business of etymology runs up against the rules and laws that it itself had laid down.

Cold has been a part of our language since before English was English. It belongs to what is known as the ‘inherited’ part of the lexicon – this contrasts with more recently ‘borrowed’ vocabulary, such as the plentiful words obligingly received from the Normans after 1066. Prior to that fateful year, we find cold in our Old English sources. If you look it up in a dedicated dictionary, it will inform you that its Old English forebear is ceald.

Some caution, though: this is one variant of the word, used in the south of England. Just like the present-day language, English in this un-Norman-ised era was riven with geographical diversity. The folk of Wessex and Kent might have said ceald, pronounced with an initial /t͡ʃ/ sound (as in cheese). Yet further north, the variant was cald with a hard /k/.

We find the ‘Anglian’ version cald in the melancholy Seafarer, preserved in a tenth-century collection of poems. It speaks to us of a lonely sailor battling winter winds on the ice-cold sea.

“… Calde geþrungen

‘… By cold constricted

wǣron fēt mīne forste gebunden,

caldum clommum; þǣr þā ceare seofedun

hāt ymb heortan; hungor innan slāt

merewērges mōd…”

were my feet, bound by frost

in cold clasps; where then cares seethed

hot about the heart; hunger tears from within

the sea-weary soul…’

The Seafarer

It was from cald, not ceald, that Modern English gets cold. The latter yielded to the former over the course of the Middle Ages. Southern ceald makes occasional appearances in Middle English as “chald” and “cheld”, including in the conspicuously archaic language of the Ayenbite of Inwyt (dialectally dissected in the previous post).

In the initial sound of the word cold, we therefore unearth a history of divisions within the fabric of English speech.

Cold is not without friends abroad. On the linguistic basis of German kalt, Dutch koud, Norwegian kald, Swedish kall, and other relatives, we can propose that it was a word in their common ancestor, Proto-Germanic. Speakers of that tongue knew it as *kalda-, a word whose prehistoric status is indicated by its prefixed asterisk.

What I like most about *kalda- is that it was a past participle in their language, something halfway between an adjective and a verb, meaning ‘made cool’. In the same way that written corresponds to write, eaten to eat, or played to play, *kalda- was a past participle serving the verb *kalan- ‘to be cold’. The latter limped into our written record of English, occasionally appearing as calan ‘to be cold’. You’d use this to say you were cold in Old English. The verb has since been lost from English, while its offspring, cold, has outlived it by several centuries.

At the heart of cold is a root, a meaningful core, to which other elements could be affixed. It’s the *kal- bit that *kalda– and *kalan- had in common. Today, this root is something that cold shares with the similarly frigid words chill and cool.

Their differences in vowel and starting consonant are products of sound change, and also the phenomenon of ‘ablaut’, something I’ve explored in a previous post. Like how sing can alternate its vowels to become sang or sung, the separation in vowels between cold and cool is a relic of this ancient system of vowel-swapping.

At work behind these Germanic words is a common root. To acknowledgeable its possible vocalic variation, we can refer to this root as *kVl-, in which V stands for the changeable vowel. It’s now bordering on algebra. The consonants on either side of V were what really conveyed coldness in English’s prehistoric forefathers.

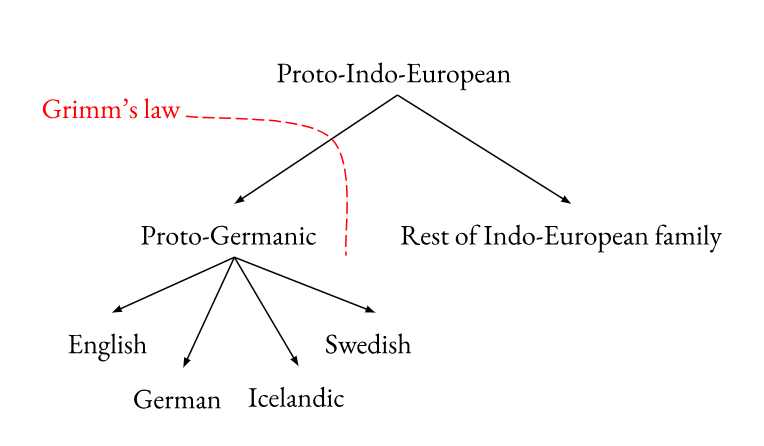

Such was the state of affairs in Proto-Germanic, the immediate ancestor of the Germanic languages. To excavate our root more deeply, we must pass through the shifts of Grimm’s law. This serial sound change, a darling of philologists, was a defining quality of Proto-Germanic that separated its branch from the rest of the Indo-European tree.

One of the series of shifts was the change of the voiced sounds *b, *d and *g into voiceless *p, *t and *k. This is how the inherited lexicon of English has knee and corn, while Latin (a non-Germanic language) has genū and grānum. The inverse of that change gives us a rule stating that whenever we have a Proto-Germanic *k, it was previously Proto-Indo-European *g.

This all is relevant to our root; we can propose *kVl- was once *gVl-.

To build the case that this root really was part of PIE, mind you, we need at least one more foundation from elsewhere in the family tree. That is to say, we need examples of the root *gVl-, meaning similar things, from other Indo-European branches. Do we have such findings? If you like to eat gelato, then you’ll know that we do.

In Latin, we find cold words containing the root gel-, including gelū ‘frost’, gelidus ‘icy’ and gelāre ‘to freeze’. This root is a match with the Germanic in both form and meaning. On the two legs of Latin and Germanic, we can therefore reach up to Proto-Indo-European and grasp a common root for frozen things like *gVl-. Ideally, we would have a wider set of words that would build a surer base. Yet further evidence consists of some suspicious Slavic and a single scrap of Greek. The two pillars of Latin and Germanic will have to suffice to reconstruct *gVl-.

From this single source come English’s inherited words cold, chill and cool. Moreover, via Latin and its descendants (like Italian and French), we then have the acquisitions of gelato, congeal, gelatin, gel and even jelly.

The initial sounds of this set of cousins have changed since the days of Latin and Proto-Germanic. The trio of cold, cool and chill would’ve once been united in a voiceless stop /k/ in the days of Proto-Germanic. Likewise, gelato, congeal, gelatin, gel and jelly we pronounce with a /d͡ʒ/ sound, but this would’ve been a guttural voiced /g/ in their Latin antecedents. Whatever the sounds were and have become, though, the two groups retain an ancient voiceless/voiced split. Grimm’s law continues to be a fault-line in English vocabulary.

So far, so neat. This collection of words connects up at a prehistoric point according to predictable, generalisable rules like Grimm’s law. It’s an instance of when historical linguistics is almost at the level of the mathematical in its systematicity. Yet sometimes, the system crashes. There is in fact another Latin word, which contains the same two consonants found in gelū, gelidus and gelāre, and which has a sub-zero subject matter. This is the noun glaciēs ‘ice’. You may recognise it from English terms like glacier.

Given the good match in meaning and shape, it’s counter-intuitive to say that it’s difficult to graft glaciēs onto the family tree. The sticking point is explaining how *gVl- might also be the root behind glaciēs. While Indo-European languages historically had no problem swapping or deleting vowels, we lack the laws to explain how the vowel within the root *gVl- might be lost and then have an /a/ vowel added after it – in other words, how we get from *gVl- to the gla- in glaciēs.

I’ve read a couple of theories; one is that glaciēs does contain the same root as in cold and gelato, but was also influenced in its form by the unrelated word aciēs ‘sharp edge’. This isn’t convincing, since an affinity in meaning between aciēs and glaciēs feels missing. In trying to connect glaciēs to gelū, our trust toolkit of rules and concepts struggles to fuse the former onto the established word family to which cold and gelato belong. Experts for the moment seem to have given up on finding any family for the etymologically orphaned glaciēs.

So, that was a stroll through the wider world behind our English word cold. Keep warm out there, and if you celebrate it, I wish you a wonderful Christmas. If you don’t, I wish you a December no less lovely.

END.

If you’d like more etymologising on a winter theme, do have a look at my seasonal posts for 2021 (Rockin’ Around Etymology), 2023 (Christmas Trees and Etymologies) and 2024 (A CHRISTMAS Full of Etymology).

References

- bosworthtoller.com

- De Vaan, M. (2008). Etymological dictionary of Latin and the other Italic languages. Brill.

- oed.com

- Pokorny, J. (1959-1969). Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Francke.

Original website post. All images either my own or taken from Wikimedia.

When & how switched French & Italian to chaud / caldo & froid / freddo?

Froid / freddo could be related to freeze (or frieren in German [my native language]). Caldo has the opposite meaning of cold.

LikeLike