Reading time: quite a while

Having dedicated over four years of my life to the subject, I have one or two thoughts about the word order of Proto-Indo-European. Somebody somewhere had to have them.

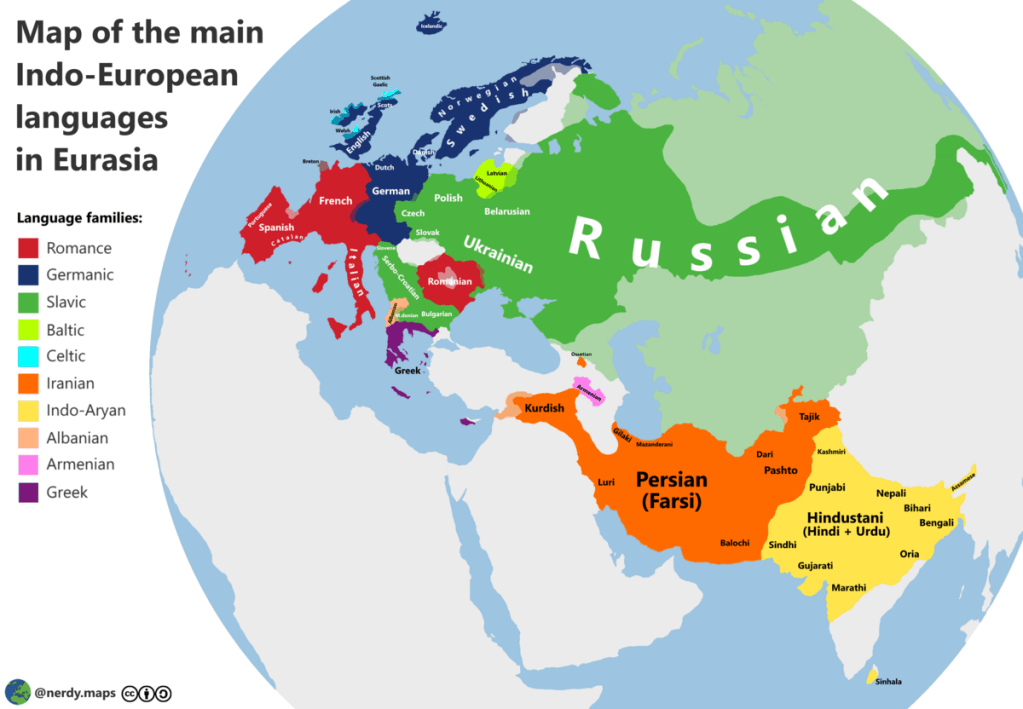

This reconstructed language – the ‘lost’ common ancestor proposed to explain the countless similarities across the Indo-European languages – has nowadays attained an impressive level of detail, as we have a good idea of what sounds and words we need it to have had. This achievement extends to its word order. Ever since the nineteenth century, scholars have speculated about the syntax of the prehistoric language that spawned the Indo-European family that we know and love.

Perhaps chief among these proposals is the idea that Proto-Indo-European had a normal and default word order of Subject-Object-Verb, or SOV for short. This is to say, it would translate English clauses like I like him and the dog chased the cat with the order ‘I him like‘ and ‘the dog the cat chased‘, putting the clause’s subject first, the verb last and the object in the middle.

This is a well-established view. However, after the aforementioned four years of study, I’ve arrived at wondering whether it should now be put to bed. In this post, I’ll attempt to explain my reasons for such historical-linguistic heterodoxy.

In introductions to the whole concept of Proto-Indo-European, it’s normal to find a statement, usually at the end of the chapter, about the word order of this prehistoric language. Here are two, taken from English-language books on the whole Indo-European family:

“While Proto-Indo-European was probably basically SOV, it also, on the basis of the attested early IE languages, allowed considerable freedom of constituent order, for instance with constituents being proposed for purposes of pragmatic highlighting”

Comrie 1997: 90

“Indo-European was basically an SOV language, and verb-final was the ‘default’ position … but the operation of a variety of movement rules served to complicate and obscure the word order picture”

Watkins 1998: 68

In other words, Proto-Indo-European most likely on some fundamental level had a word order of Subject-Object-Verb, which the language allowed to be modified and played around with. These are summarising sentences written by eminent and erudite linguists, so I do not dare to say that they are outright wrong.

The idea that “PIE = SOV” is also a view with some serious pedigree, going back at least to the German scholar Berthold Delbrück at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It then received a serious boost in the 1970s, first with the work of Winfred P. Lehmann. His Proto-Indo-European Syntax (1974) consistently refers to the proto-language as SOV or just OV, although for Lehmann the short label of ‘OV’ concerned so much more than the arrangement of objects and verbs, but rather described word order across the board. Calvert Watkins then in 1976 agreed with this view, on the basis of archaic phrases identified across the Indo-European languages.

We must bear in mind that all and any claims about Proto-Indo-European can only be based on the evidence of its documented daughters. These are primarily Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit, Hittite, Avestan and the rest of the merry gang of historical languages for which we have a written record (altogether: ‘early Indo-European’). What collective and comparative evidence they offer then allows us to hypothesize about Proto-Indo-European.

Across this group, an SOV order is indeed extremely common, albeit not universal. It appears with varying frequency from language to language, and even author to author. For an example, take the Latin writings of Julius Caesar, who really liked constructing SOV clauses:

“Quā dē causā Helvētiī (S) quoque reliquōs Gallōs (O) virtūte praecēdunt (V), quod ferē cotīdiānīs proeliīs cum Germānīs contendunt (V), cum aut suīs fīnibus eōs (O) prohibent (V), aut ipsī (S) in eōrum fīnibus bellum (O) gerunt (V)”

‘For which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valor, as they contend in almost daily battles with the Germans, when either they repel them from their own lands, or they themselves on their frontiers wage war’

Latin. Julius Caesar, Gallic War 1.1

Or take some Classical Greek, from the fifth century BC:

“Kambúsēs (S) dè tà mèn parà Libúōn elthónta dôra (O) philophrónōs edéxato (V)”

‘Cambyses received the gifts from the Libyans in all kindness’

Ancient Greek. Herodotus, Histories 3.13

Or a brief bit of Vedic Sanskrit:

“Sá (S) devā́m̐ (O) éhá vakṣati (V)”

‘May he bring the gods here’

Vedic Sanskrit. Rigveda 1.1.2

Or even from among our early fragments of the Germanic languages:

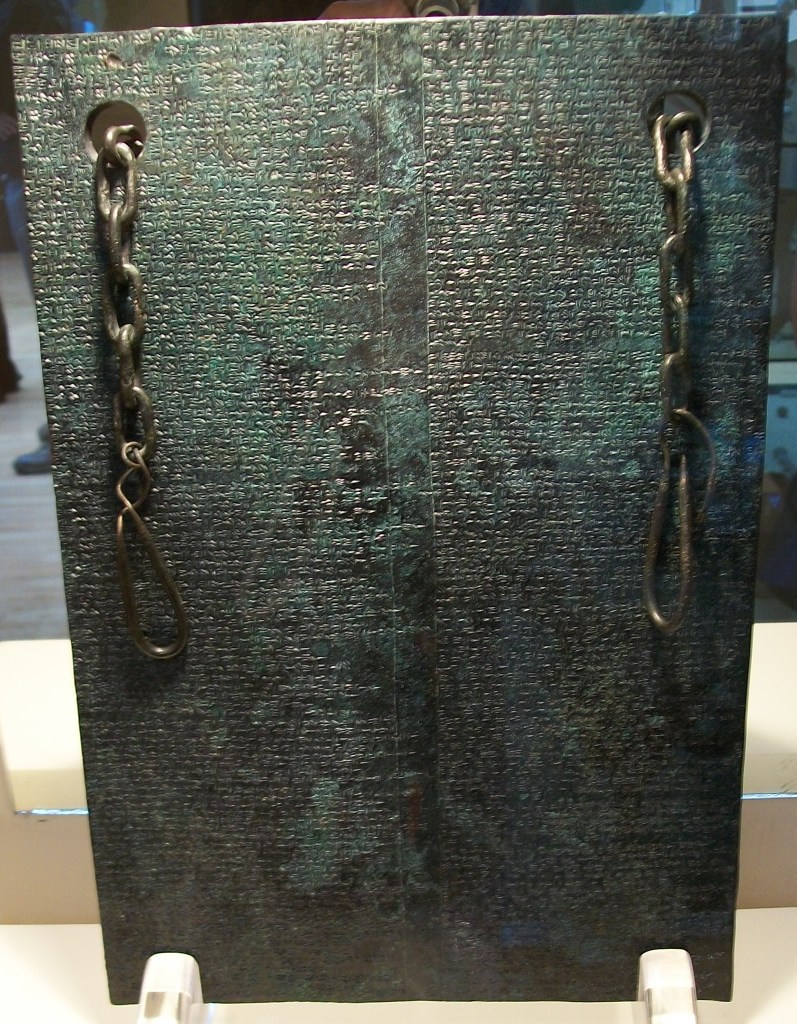

“Ek Hlewagastiz Holtijaz (S) horna (O) tawidō (V)”

‘I Hlewagastiz Holtijaz made the horn’

Proto-Norse. Inscription on one of the Horns of Gallehus

Consequently, across grammars and papers on individual early Indo-European languages, you will typically find the same general description that these languages are “basically”, “fundamentally”, “neutrally” or “traditionally” SOV in their word order. For example, it was the option of Delbrück for Sanskrit:

“Die traditionelle Wortfolge in einfachen unabhängigen Sätzen lässt sich in folgende Regeln fassen:

1. Das Subject eröffnet den Satz

2. Das Verbum schliesst den Satz

3. Die übrigen Satzteile werden in die Mitte genommen“

‘The traditional word order in simple, independent sentences can be summarised in the following rules: 1. The subject opens the sentence; 2. The verb closes the sentence; 3. The remaining parts of the sentence are placed in the middle’

Delbrück 1888: 16

Likewise, it was how the great Latin scholar Harm Pinkster summarised the general opinion of Classical Latin word order:

“The standard view in Latin linguistics is that Latin essentially had a S(ubject) O(bject) (finite) V(erb) word order … However, as my use of the word ‘essentially’ suggests, many deviations from the basic SOV word order are recognized”

Pinkster 1990: 69

Hittite, an ancient branch of the family tree deciphered in the 1910s, was found to agree with the same description applied to Latin, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit:

“The functionally neutral or “unmarked” word order in Hittite is S(ubject) O(bject) V(erb) … Various discourse factors not infrequently lead to deviations from the neutral S-O-V word order”

Hoffner & Melchert 2008: 406

Having spent a lot of time with these languages and their experts, I find it hard to disagree with such descriptions for Latin, Sanskrit, Hittite and the rest (except maybe Ancient Greek) – provided that the descriptions stick to the frequency of SOV. I have less of an issue with describing Classical Latin or Hittite as predominantly or typically SOV, because this is only a statement on the statistics of the attested word order.

I do take issue though with the claim that the high frequency of SOV therefore points to something deeper or fundamental about Indo-European word order, as I will try to explain now through three objections – or rather, personal points of contention and confusion.

Objection 1: Clausal Bias

The first objection is more of an appeal for clarification and specification. The view that early Indo-European languages, and therefore their common ancestor, ‘were SOV’ works better for some types of clause than others. The label of SOV seems to be rooted in what we call declarative main clauses – combinations of verbs, nouns and other words that together express simple statements of fact, like the sky is blue or cats are great. If we first specify that this is the type of clause that we have in mind, then yes, SOV does appear to be the norm.

Over the past four years, I found that there is great word-order variety across different clause types in Indo-European languages. My view is that SOV holds well for facts and also wishes, but less well for questions and commands.

Early Indo-European interrogative clauses, for example, display such a strong tendency to put the question word first or second that this seems to be a principal rule behind their word order (known as ‘wh-movement’). Even my beloved Old Irish, famous for its ‘VSO’ clauses, displays this phenomenon, which I argue is an inheritance from the family’s proto-parent. Likewise, early Indo-European imperative clauses, expressing direct commands, like to place the commanding verb first, or at least early on, before any objects.

In my view, to describe all of Proto-Indo-European as ‘SOV’ is firstly too broad and sweeping. It should at least be qualified with a specific type of clause to which it applies. You could argue that the language’s declarative clauses were somehow primary and basic, and that other types of clause were riffs off them and their fundamental SOV structure, but I reckon that you would have a theoretically hard time defending this.

Objection 2: Changing the Subject

The second objection stems from my squeamishness over the very terms subject and object, and an undefined sense of uncertainty over their relevance for Proto-Indo-European. The subject of a sentence is one of those linguistic terms (along with word) that elude easy definition when you try to pin them down. This is not to say that subject is a useless grammatical label, but rather that it may mask a variety of phenomena, and vary in usefulness across different languages.

In English, the concept of a sentence’s subject is a meeting point between word order, topicality (see Objection 3), grammatical case, and function in the sentence. There does not seem to be one common thread of subject-ness, but rather a mixed bag of qualities. For example, take the sentence

- I hear the man

The pronoun I functions as the agent or experiencer of the hearing, and also occupies the pre-verbal position associated with subjects. We can quite reasonably refer to I as the subject. Now take the passive sentence

- I am heard by the man

Here, I is no longer the hearer, but rather the heard. While it is no longer the agent of the hearing, we would still think of I as the subject, because it maintains the subject position, is the topic of discussion, and appears in English’s limited nominative case. This is opposed to its non-nominative form, me. We tend not to think of me as a possible subject, even if it is the do-er of the action.

- The man was heard by me

Me may do the hearing here, but I’ll wager it’s not the subject for anyone. Even the pre-verbal position is not a guaranteed quality of subject-ness in English, as in the archaic-sounding clause

- Under a tree heard I a man

Here I is restored to agency as the hearer, but its position relative to the verb has changed. Does I remain the subject here too? I argue that the consistent co-occurrence of certain phenomena allow us to feel like there is in English something concrete about the concept of ‘subject’, but it may be a mirage.

In an early Indo-European language like Latin, we have an even more complex interplay between different phenomena behind its subjects. There is no one-to-one alignment of function, case and word order. The agent or experiencer of an action may appear in the nominative case, but also in the dative (e.g. mihi placet… ‘I like…’). The nominative case can meanwhile be used for the recipient or target of a passive verb (e.g. domus laudātur ‘the house is praised’). Nominative nouns and pronouns can appear in a greater variety of locations in the Latin clause, removing the sense of a clear position reserved for ‘the subject’.

Try to grasp a steady concept of subject and also object in Latin, and your fingers clutch at linguistic fog. Other early Indo-European languages are similar in the lack of clear criteria for subject-ness, and object-ness too. On their collective evidence, I question the terms’ relevance for the family’s common origin, Proto-Indo-European. Can we label the language ‘SOV’, if we are not sure its grammar even included such categories as ‘S’ and ‘O’?

Objection 3: Discourse Dominates

The final objection, which I consider the most serious, is a matter of context and conversational flow. It is generally agreed that individual early Indo-European languages like Latin and Ancient Greek adapted the word order of their sentences according to the larger conversation to which a given sentence belongs. This is usually referred to in the literature as discourse information.

For example, if a thing or event has been established previously, then that topic of discussion will come at the beginning of the sentence. What follows is then the new information about that thing, referred to as the predicate or comment. The comment typically contains the verb and an especially important piece of the new information, known as the focus.

Known information first, new information second – it’s a sensible way to construct a sentence and link it to what’s gone before. English does this too, although English is more limited in its ability to muck around with word order, compared with older Indo-European languages. Nonetheless, English can use different words, word order, passives and special intonation to indicate a topic or a focus. All the while, the basic event remains the same.

- The woman bought the apple on Wednesday

- The apple was bought by the woman on Wednesday

(the apple is made topical through a passive structure) - That apple, the woman bought it on Wednesday

(the apple is made topical through fronting, the determiner that and the resumptive pronoun it) - The woman bought the apple on Wednesday

(the apple is made focal through emphatic intonation, contrasting it with some other fruit)

Scholars agree for the individual Indo-European languages and for Proto-Indo-European itself that discourse information played a considerable role in determining their word order. Long passages of Latin prose or Greek oration will typically flow in waves of changing topics and comments; in speech, this may have been accompanied with a rise-and-fall intonation for the overall clause, reaching a peak with the focus and tailing off with the verb. These factors are what is meant by the “discourse factors” and “pragmatic highlighting” in the quotations above. For another example, on Hittite:

“Despite the claim for rigid SOV word order above, the relative placement of S and O to each other is frequently determined not by their grammatical function, but by their information structure: e.g., the canonical SO word order is determined by the dominant topical status of subject and focal status of object. If subject is contrastive focus and object is topic, the order is reversed”

Sideltsev 2015: 80

Nonetheless, many (most?) scholars would still maintain that SOV was the basic arrangement, the fundamental order in early Indo-European and therefore its parent language also. I presume they would do so on the basis of its high frequency in our historical sources; for them, it was on a bedrock of SOV that discourse information then operated.

Yet certain dissenting voices have led me to query this. In particular, research into Ancient Greek and its often bewildering word-order patterns foregrounded for me the importance of discourse information, while almost removing the matter of subjects and objects from the scene. Another source of doubt come from Harm Pinkster, who wrote about Latin in 1990:

“What evidence is there for assuming a basic SOV order in Latin? Not much … The existence of so much variation itself in our texts should warn us against assuming a syntactic basic order. The variation can be explained much better if we assume the existence of several different orders reserved for specific situations (text type, sentence type, constituent type, etc.) or assume other (pragmatic and/or semantic) factors to determine the order of constituents”

Pinkster 1990: 70-1

Yet even in cases when SOV can be recognised as the most common word order in a given early Indo-European language, the bigger blow to the basic-ness of SOV came for me in a remark of John J. Lowe’s, when he wrote that Sanskrit’s typical SOV order was the most common arrangement

“… given the typical information-structural arrangement of a clause”

Lowe 2015: 38

The objection is therefore that SOV might be yet another product of arranging words into topics, comments and focuses (or foci). In other words, SOV is not ‘basic’ at all, but arises from the same principles that could also produce SVO, VSO and OSV orders. The frequent occurence of SOV does not indicate a fundamental structure, but rather stems from the close association between subjects and topicality, and between objects and focality.

As mentioned above, there is ambiguity in the terms subject and object. Nonetheless I do not think they are being used by scholars as straightforward synonyms for topic and focus when discussing SOV word order. If they were, then yes, early Indo-European and Proto-Indo-European could be considered SOV, because the Topic-Focus-Verb arrangement was clearly the dominant structure. However, I do not think this is the intended meaning.

If the subject and object terms of SOV are also understood to include the grammatical functions and relations of do-er and undergo-er, and to be linked to specific grammatical cases, then I think the evidence does not support the view that SOV was an fundamental arrangement. It held no syntactic privilege in Proto-Indo-European and its offspring; it was ‘equal’ in discourse-sensitivity with other documented orders.

Conclusions

I hope that the previous paragraphs have communicated my case against describing Proto-Indo-European as ‘SOV’. In my view, there are too many problems with this brief label to consider it accurate or helpful when discussing the proto-language and many of its early descendants. It seems to me an empty designation, too general and too ambiguous to tell us something concrete about the word order of the prehistoric language.

Scholars who agree with me may nonetheless still want to claim that SOV or some other structure was fundamental in Proto-Indo-European for ‘theory-internal reasons’ – that is, because of the syntactic school of thought they belong to.* I won’t outright disagree that there may have been more syntactic structuring going on underneath the surface of the languages in question, but the surface is all we today have. A glimpse of the surface of Proto-Indo-European is therefore all those languages offer us.

In producing the documented word order of Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit and the rest, it was the Topic-Focus-Verb system that had the final say, or at least considerable power. It is the output of this system that we have to use to get back to the word order of Proto-Indo-European, and the prescence of this schema across its elder daughters indicates that the proto-language operated through it too.

Perhaps then it would be fruitful to retire the label of ‘SOV’ for Proto-Indo-European, or pause the hunt for its basic arrangement of those clausal components. Considering it to have been principally TFV, instead of SOV, could put the whole endeavour of tracking the developmental paths of Indo-European syntax on firmer foundations.

From this departure point, I feel we can better understand the interesting and distinctive changes that the ancestral syntax would then undergo across the expanding family of languages, such as in its later Celtic, Germanic and Romance branches.

The more I think about Proto-Indo-European grammar and word order, the more it reminds me of an entirely different language family: the Uralic languages. What I’ve sketched here for the ancient proto-language holds pretty well for modern-day Hungarian, for example.

“… the order of major sentence constituents is just as strictly constrained in Hungarian as it is, for example in English or French – merely the functions associated with the different structural positions are logical functions, instead of the grammatical functions subject, object, etc.

É. Kiss 2002: 2

The Hungarian sentence can be divided primarily into a topic part and a predicate part.”

Moreover, while recording an interview about Mari (a Uralic language in Russia, and therefore one much less bothered by European linguistic patterns), its discourse-determined word order and lack of finite subordinate clauses struck me as a living example of the grammar that I propose for Proto-Indo-European.

Now, it would not be right to make the bold claim that these syntactic commonalities are evidence for some kind of distant connection between Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic. I won’t deny though, it is tempting.

END.

Footnote

* They may alternatively want to claim that subjects, objects and verbs had no fundamental ordering or hierarchy. Such a ‘flat VP’ has been proposed for individual Indo-European languages (for example, see Cervin 1990 on Ancient Greek).

References

- Bate, D. L. (2024). Reconstructing the left peripheries of Proto-Indo-European. PhD thesis. University of Edinburgh.

- Cervin, R. S. (1990). Word order in ancient Greek: VSO, SVO, SOV, or all of the above? PhD thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Comrie, B. (1998). The Indo-European linguistic family: Genetic and typological perspectives. In The Indo-European languages. 74–97. Routledge.

- Delbrück, B. (1888). Altindische Syntax. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses.

- É Kiss, K. (2002). The Syntax of Hungarian. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoffner Jr, H. A., & Melchert, H. C. (2008). A Grammar of the Hittite Language: Part 1: Reference Grammar. Penn State Press. First edition.

- Lehmann, W. P. (1974). Proto-Indo-European syntax. University of Texas Press.

- Lowe, J. J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The syntax and semantics of adjectival verb forms. Oxford University Press.

- Pinkster, H. (1990). Evidence for SVO in Latin? In Latin and the Romance Languages in the Early Middle Ages. 69–82. Routledge.

- Saarinen, S. (2022). Mari. The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. 432–470. Oxford University Press.

- Sideltsev, A. V. (2015). Hittite Clause Architecture. Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale, 109(1). 79–112. Cairn/Softwin.

- Watkins, C. (1976). Towards Proto-Indo-European syntax: problems and pseudo-problems. Papers from the Parasession on Diachronic Syntax. 306–326. Chicago Linguistic Society.

- Watkins, C. (1998). Proto-Indo-European: Comparison and Reconstruction. In

The Indo-European Languages. 25–74. Routledge.

Images taken from Wikimedia Commons. With thanks to Jakub and Yoïn for independent sources of encouragement to write this.

It’s great!!!

JUDr. David Uhlíř

Envoyé de mon iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice. I never thought the SOV issue made much sense for non-configuration languages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Truly non-configurational languages are very rare. Nunggubuyu is one; it does things IE can’t dream of, and vice versa.

LikeLike

It’s true that “subject” doesn’t make sense for all languages; a good overview over how different languages treat agents, patients and experiencers is here, though it lacks the direct/inverse languages. But this is all beside the point here; all the old IE languages lump agents and experiencers as, well, subjects and distinguish them from (…animate…) objects.

I do like the main thesis, though; topic & comment are widely underappreciated, especially for “Standard Average European”.

“The agent or experiencer of an action may appear in the nominative case, but also in the dative (e.g. mihi placet… ‘I like…’).”

That’s neither the agent nor the experiencer, it’s the beneficiary. The subject, in this case the experiencer, is the thing you like; that’s what’s in the nominative.

Actual subjects that are in the dative and cannot be explained as beneficiaries occur in Icelandic, but not even in my native German.

LikeLiked by 1 person