There’s a certain air of femininity around the letter A.

For one reason, it brings a great number of modern female first names to a close. A sample of famous names, especially if skewed towards the West, will typically include a fair few examples. Among the female winners of a Nobel Prize, we find Claudia, Bertha, Rigoberta, Gabriela, Donna, Svetlana and several others, united by both the accolade and their names’ final letter. The first ladies of the United States over the past 100 years have included another Claudia, a Thelma, a Barbara, a Laura and a Melania twice. In a somewhat less august list, eight of the nine ladies cited in Lou Bega’s 1999 hit Mambo No. 5 also bear names that end in A.

But the association between A and the feminine goes beyond proper names, of course. Several national and international languages rely on the letter and its sound to help assign nouns to a feminine grammatical gender. Some of these words have travelled into English (e.g. from Spanish: vanilla, armada, salsa).

The gender and the A are then shared with nouns’ associated words, like adjectives and determiners. To render a tall woman into Italian would be una donna alta, just as the dear grandmother in Spanish would be la querida abuela. The same association holds in other linguistic corners of the world. In my local Slavic language, Czech, short A and long Á string together phrases about female folk like:

ta nová, slavná a úspěšná žena přišla a ona je spokojená

‘that new, famous and successful woman has arrived and she is pleased’

Perhaps you’re now wondering why? What’s the reason for this apparent correlation between vowel and gender? Is there something intrinsically feminine about it? (No.)

As a historical linguist, my very short response would be: it’s because of Proto-Indo-European. But that, except to a handful of already au-fait nerds sagely nodding in agreement, would be a deeply unsatisfying explanation. So, what follows is my less short response. This examination of grammatical gender (not the first on here, likely not the last) will take you, dear reader, into a world of ancient speech and grammatical computation, and ultimately up against the bars of the cage of linguistic thinking. Brace yourself, and keep an eye on the nerdery level of each section, lest you be exposed to levels that you cannot handle.

The feminine A across Indo-European

(Nerdery level: 2/5)

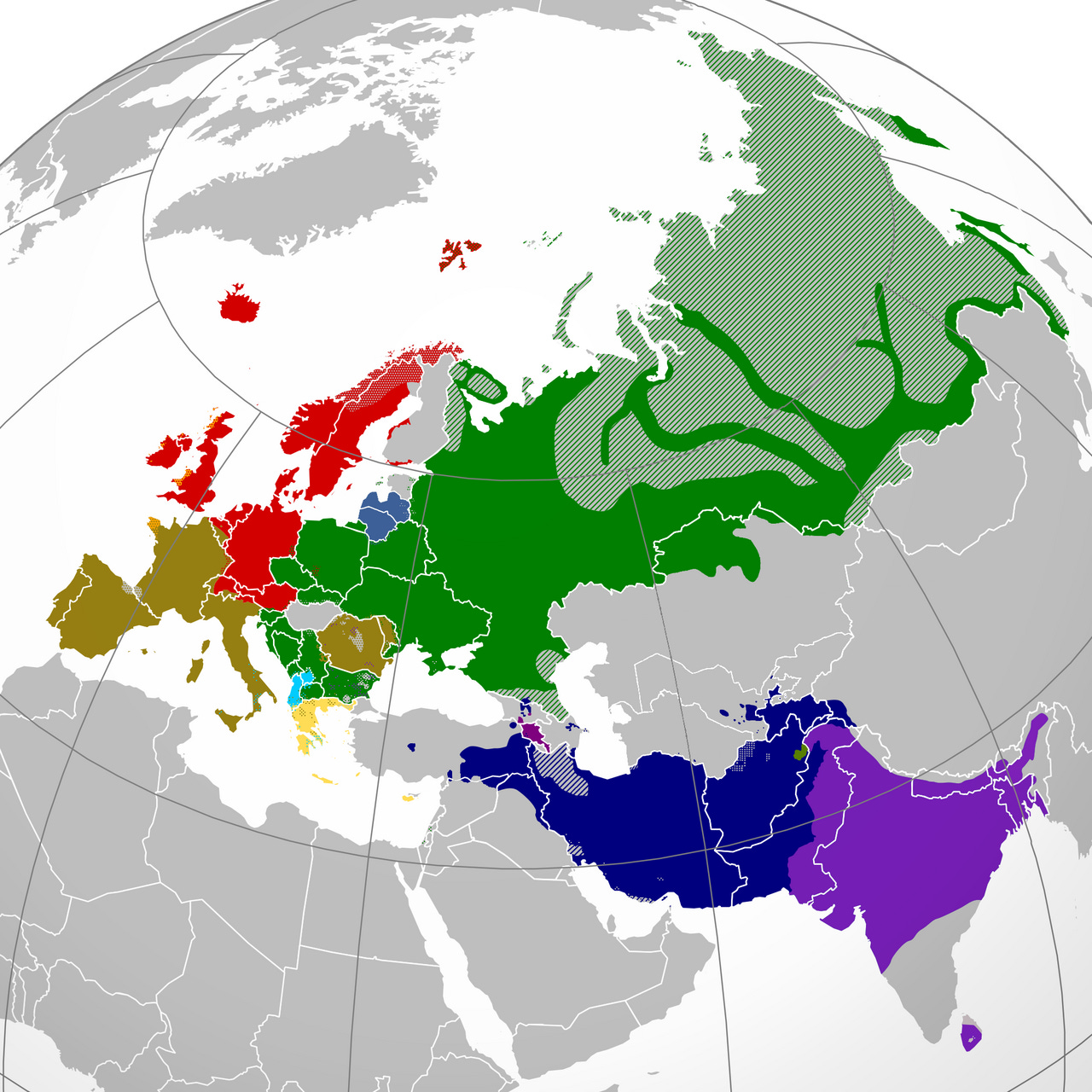

The single reason for so much of the aforementioned phenomena is a particular family of languages: Indo-European. This wide grouping embraces French, Spanish, Romanian, Greek, Kurdish, Persian, Hindi-Urdu, Armenian, Albanian, Pashto, Polish, our own dear English, and countless others.

It is of course perfectly possible for speakers of languages outside of Indo-European to coin and wield names that end in A, just as many female names forged within Indo-European may terminate otherwise.

With some names, the story is complicated. The Semitic name Maryám/Miryám was introduced by Christianity into the Indo-European fold, and became Ancient Greek María. This jump in language family saw it gain a final A. It then lost this through regular sound change on its way to becoming French Marie and English Mary.

Nonetheless, there is a millennia-old connection at work in Indo-European languages between A and things feminine. This is because of the languages’ shared ancestry; once upon a time, they were one. During those early days, a class of words, characterised by A, was set up by speakers of Proto-Indo-European.

This development was prehistoric, prior to our historical sources, but we can believe in it on the basis of descendant languages. The use of feminine A-endings is something that most branches of the family tree have exhibited at some point, although they differ as to how long it has remained a part of them.

For example, Latin had a whole class of nouns defined by the vowel A, nearly all of them feminine in grammatical gender. This ‘first declension’ unsurprisingly included nouns like fēmina ‘woman’ and puella ‘girl’. Yet it contains a majority of words with no connection whatsoever to humanity or its different flavours: mensa ‘table’, taberna ‘hut’, āra ‘altar’, fortūna ‘luck’, and many more.

The feminine A is very visible in ancient Indo-European languages, such as Latin and its distant cousin, Sanskrit. The latter has a whole set of feminine ‘ā-stems’. Again, some of these are obviously female in their meaning (e.g. gajā ‘female elephant’) but others not at all (e.g. sénā ‘army’).

This behaviour of Latin and Sanskrit words instantly drives a wedge into any idea that human gender and grammatical gender map onto each other. Their relationship is complex; they are separate phenomena, but not entirely unconnected. The former can shape and drive the latter. If speakers recognise that one of their grammatical genders happens to contain many words relating to a particular gender or sex within a species, they may strengthen the association by assigning new similar-meaning words to that grammatical gender, or even by switching the gender of existing words. Nonetheless, this is just an association, and some of the world’s languages have genders (also called ‘word classes’) that work differently. Others don’t reflect human categories in their grammar at all.

Many modern descendants of ancient Indo-European, like Spanish and Italian, have maintained the A-class of words up to the present day. But another daughter of Latin, French, has seen that A modified into E via sound change. This E is still a signifier of the feminine; it can be read, and less often heard, at the end of French nouns, adjectives, verbs and personal names. Some of the last group have made it into English, like Caroline and Diane.

Sound change has altered the original feminine Α elsewhere in Indo-European. Greek is a branch separate from Latin, and it has for centuries had alpha-final feminine nouns (e.g. thálassa ‘sea’, sophía ‘wisdom’) and names (e.g. Kleopátra), but it used to have many more. A large chunk of them in antiquity underwent a change from alpha to eta. This context-dependent shift took feminine nouns and names like níka (‘victory’) and Heléna, and turned them into níkē and Helénē. It was originally limited to the Attic and Ionic dialects of the ancient language, leaving us plenty of evidence for the feminine alpha elsewhere. But because it was from Attic, with Ionic input, that a unifying Greek language later emerged, these eta-final feminines have become a fixture of the modern standard.

English itself belongs to a branch of the Indo-European tree that changed and lost the feminine A centuries ago, long before our written record begins. Its branch is Germanic, and our earliest prose texts for this sub-family, composed in the 4th-century Gothic language, show that Germanic had shifted the feminine A into a long О̄ vowel. A few centuries later, when we get our first texts in Old English, we see that long О̄ has been reduced. It’s either absent or a short vowel, like the U of giefu (‘gift’) and granu (‘moustache’). Bearing this ending went hand in hand with belonging to the feminine gender, one of three categories that English grammar used to have. Both the categories and the endings would in time whither away, part of the loss of structural complexity that characterises the history of English words.

At this stage, I can offer a preliminary answer to the question of why a final A is feminine: because many of the words and names that exhibit it come from Indo-European languages, and these historically have employed an A-ending for words that are grammatically and humanly feminine. This goes back to a single feminine ending in their common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European.

Some members of the family have retained the A (Spanish, Italian, Slavic languages); others have modified it (Greek, French) or lost it (English). Within the first group are languages, like Latin and Spanish, that have happened to gain cultural prestige, and consequently have donated A-final words and names to other languages.

But we word nerds want to dive to great depths. Why did A become this marker of femininity? How did it start? And why does this ancient A-class include a bulk of words that have nothing to do with women, femininity or humanity in general? Take a deep breath, and follow me deeper still.

Shifting genders in prehistory

(Nerdery level: 4/5)

Strange to say, the feminine gender and its characteristic A are comparatively young. We have evidence for an early stage of Indo-European without them.

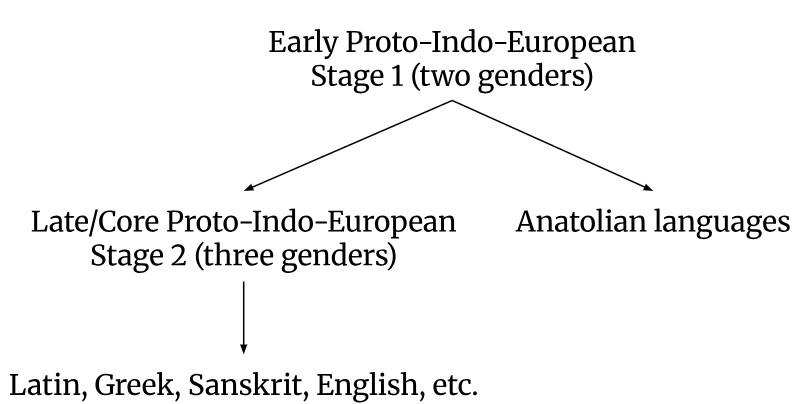

The assembled evidence has allowed scholars to identify two stages within the prehistoric development of Indo-European speech: a later stage with three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), and an earlier stage with only two. These word groupings are generally labelled the animate and the inanimate.

Rather than any sub-types within humanity, speakers sorted between things that speakers recognised as self-moving, living, active individuals, and non-self-moving, non-alive passive objects and substances. A human, a horse or a bird would likely be assigned to the animate word class. Stone, water, earth, wind and fire would be grammatically inanimate.¹

The difference in animacy was expressed in the word’s ending, and was actually very minimal. Animate words would end in *-s if they were the do-er of the action (the nominative function). They bore the ending *-m if they were having the action done to them (the accusative function). We have a wealth of historical evidence for these prehistoric endings; Latin for example displays them in deus (a nominative god) and deum (an accusative god). Inanimate words, meanwhile, did not have this distinction. Their ending stayed the same regardless of whether they were nominative or accusative. This is a rule that has continued across the Indo-European family.

As a nerdy aside, this ancient grammar is reminiscent of ergative-absolutive languages (like Georgian and Basque). Also, the difference between the two classes was so slim that it’s possible to envisage a pre-prehistoric time when there were no classes or genders in Proto-Indo-European grammar at all. Such a situation is conceivable; it’s how Uralic languages (like Finnish) and Turkic languages (like Turkish) have functioned for centuries.

How we get from Stage 1 (animate, inanimate) to Stage 2 (masculine, feminine, neuter) is that the animate gives birth to a third grouping. Like Eve from Adam’s rib, the feminine gender began life as a subset of animate words. The feminine having established itself, the remainder by default became its counterpart masculine gender. The inanimate category, unbothered, henceforth gets rechristened by scholars as the neuter.

How can we believe any of this? Newcomers might be incredulous, faced with such discussion about stages within a prehistoric language that we have no direct evidence of. But there are many traces of the earlier stage still to be spotted in Indo-European languages with the three-gender system. Older daughters, like Latin, exhibit a fair few in their declensions. Even English words still whisper of it.

For example, English preserves the ancient division in its question words: who (animate) vs. what (inanimate). Who has the archaic form whom, the rule being that who is the asker and whom the asked. It therefore changes from nominative to accusative, as animate words always would. Meanwhile, what never changes in its ending, like a good inanimate. Nominative he and she inflect into him and her, but English’s inanimate pronoun, it, does not bend.

An overwhelming flood of evidence, however, comes from the Anatolian languages, most famous among them being Hittite. Following its decipherment in the 1910s, Hittite has been found not to show a single sign of a third gender, the feminine. Instead, its grammar functioned through a two-way divide of common (animate) and neuter (inanimate) words.

This difference is explained through complexifying the family tree. While Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit, English and many others go back to that common Stage 2 point, Hittite and its Anatolian crew branched off from the rest after Stage 1. Put another way, after Anatolian-to-be had gone on its way, the remaining speakers of ‘Core Proto-Indo-European’² innovated the feminine gender that has endured .

But why? Why make your own grammar more complicated through this innovation?

Engendering a gender

(Nerdery level: 5/5)

Those speakers’ reasons for the innovation are not at all clear. I cannot stress how much of a complex debate this aspect of language history has provoked among Indo-Europeanists. The prospect of doing justice to this headache-inducing issue daunts me, but I owe it to you, my reader, to try.

There is at least agreement over the point that the A typical of the feminine grammatical gender was once a suffix – that is, an extra thing added to the end of existing words to create new ones. It found itself added to a selection of animate nouns. The accusative *-m ending could follow it in turn, being necessary to indicate the role of the animate noun in the sentence and event.

The meaning of the suffix and what it contributed to the noun are in no way obvious. It can’t have been something exclusively female-referring; there are so many grammatically feminine Indo-European nouns that have no obvious connection to women, human gender or biological sex (remember: tables, huts, altars, etc.). All speculation is severely complicated by the fact that the same suffix seems to have created plural neuter nouns too.

Across Indo-European languages, A is not only associated with the feminine, but also used as the ending for nominative/accusative neuter plural nouns. In Latin, we have templa ‘temples’, tempora ‘times’, corpora ‘bodies’ and cornua ‘horns’. The neuter has since died out among Latin’s daughters. But over in Polish, a representative member of the Slavic branch, we find the plurals miasta ‘cities’, okna ‘windows’ and piwa ‘beers’. If we assume (for reasons of economy) that the same ancient Indo-European suffix is responsible for both feminine words like fēmina and neuter plurals like templa, it’s hard to pinpoint what its original function was.

I’ve submerged myself in literature on this topic, to little satisfaction. The usage of the suffix and the question of which came first (the neuter or the feminine) baffle the experts. Their proposals include an original ‘collective’ function (creating nouns that referred to collections of things, some of which happened to be women), an ‘appurtenance’ function (indicating that the suffixed nouns belongs or relates to something else), and an origin in adjectives. Painting a good image with the available evidence is so complex that H. Craig Melchert, a truly great Indo-European scholar, ends one paper on the subject with the pessimist note:

“I have no illusions that I have come close to “solving” the problem of the rise of the Indo-European feminine grammatical gender.”

(Melchert 2014: 269)

If you want to chase this wild goose yourself, you’ll need to know that the prehistoric suffix in question is referred to in the scholarship not as *-a, but as *-h2. This is a sort of algebraic placeholder for an unclear consonant sound. It’s used for reasons that are very interesting, and really demand their own dedicated article. Until that happens, here’s Simon Roper on it.

What is semi-clear at least is there was once a suffix, added to a group of animate nouns in the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. This subset was the kernel of the A-feminine words. In time, the number of members referring to women and female entities that it contained (by design or by accident) led people to think of it as the ‘feminine’ gender. Its animate counterpart became the ‘masculine’. When this recognition occurred is unknown, but the ancient Greeks at least sorted their words into masculine, feminine and neuter. The third was the metaxú (‘between’) gender according to Aristotle. The Romans then followed suit, coining their terms masculīnus, fēminīnus and neuter (‘not-either’).

But it would take more than that prehistoric affix to turn the feminine into a fully fledged gender. What it needed was for the noun to share that affix with associated adjectives and functional words. It may seem counterintuitive at first, but what grammatical gender is first and foremost is a feature shared between words.

“Genders are classes of nouns reflected in the behavior of associated words”

(Hockett 1958: 231)

Gender is crucially something that a noun donates to other words, as a way of indicating that they belong together.

In Latin, stella ‘star’, turris ‘tower’, manus ‘hand’ and rēs ‘thing’ were all designated as feminine in gender, even though they don’t all exhibit the characteristic A. Grammatical gender is potentially so complex that it often detaches itself from the sounds and shape of its nouns. Some languages weave the shape, gender and meaning of words very tightly together; others are happy to pick the three threads apart.

Among them, the sharing of a quality between cooperating words is the essence of gender. Latin stella, turris and the rest were feminine not because of their appearance, but because they required feminine adjectives and determiners. Bonus ‘good’ and ille ‘that’ had to change into feminine bona and illa if they were to cooperate with stella or turris and provide information about the same thing.

In later Italian and Spanish, you can more or less know the gender of a word from its appearance; this was a development within non-standard Latin, arguably one for the better.

“The marking of declension class was becoming equatable to gender marking. This makes for an easier grammar than one in which gender must be learned separately from form.”

(Alkire & Rosen 2010: 195)

Revisiting my short Italian example above (“una donna alta”), if Italian nouns like donna didn’t share their gender with articles (una) or adjectives (alta), then all we’d have is a large group of Italian nouns that happen to end in A.

English has plenty of nouns that happen to end in T (cat, hat, rat), but we don’t think of them as forming a gender. If they shared that T around, then we might – that is, ‘thist bigt, beautifult and grumpyt cat’.

Luckily for the feminine gender, the suffix started to be shared between words in Proto-Indo-European phrases. Why? Because it was somewhat useful to do so. For language learners who think of grammatical gender as a nuisance and a challenge, it might seem strange to contemplate that it only survives by being useful or easy for native speakers, or both. Things that are unhelpful and hard tend not to survive in language. Grammatical gender can get started by providing a service for speakers.

In the case of Indo-European, it helped to thread words together across a complex sentence, a detail that confirmed to the listener which nouns belonged with which adjectives, verbs and determiners.

“It is a mistake to think of gender systems as systems for classifying things: to the extent that they do so it is secondary to their function to make it easier to keep track of links between constituents.”

(Dahl 2000: 113)

This was especially useful for a language that was flexible in its word order. I am well and truly qualified to say that Proto-Indo-European was such a language. Gender becomes less useful when word order is more rigid, as in the case of English. A weakening of gender might cause, or be caused by, a stiffening of syntax.

Clearer genders for English might allow its speakers more freedom to mess around with word order. We could say

I saw thist bigt cat outside the house yesterday morning beautifult and grumpyt

and we’d know that beautifult and grumpyt work with thist and bigt in referring to the cat, despite their separation across the sentence. Does that sound silly? The Romans and Greeks wouldn’t have thought so.

The limits of my language

(Nerdery level: 3/5)

Returning to the surface after this deep dive into prehistoric grammar and language change, I’m left with one final piece of reflection: that the nature and history of our languages shape our thinking and impressions. I refuse to get all ‘Sapir-Whorf’ on you here, mind you. What I mean instead is that our language gives us a sense of being natural and normal, when it is in fact arbitrary. For people thinking within the Indo-European box, there is something essentially feminine about A. New names for baby girls or products marketed at women may well be coined with A in final position. Activia yoghurts and perfumes from Sephora come to mind.

But it’s all an accident of language history. There is nothing inherently feminine about the letter A, nor the vowel that it spells. Its status today derives from a prehistoric suffix in a language whose offspring happen to have been socially successful. There are other traditions of linguistic femininity that put no such store in A. In Semitic languages, for example, the typical feminine marker is T. Native English speakers may have encountered this ending in a Jewish woman’s bat mitzvah or the name Judith (deriving from Hebrew, etymologically ‘Judean woman’).

It is us who put meaning, associations, notions and nuances into our language; we don’t discover them in it. Contemplating the feminine A and its fundamental arbitrariness are for me a path towards bumping into the bars of our caged thinking. They’re also a key for unlocking the door and stepping outside it for a while.

END.

Endnotes

- That said, we actually reconstruct two words for ‘fire’ in Proto-Indo-European. One was animate (the origin of Latin ignis), the other inanimate (the origin of English fire). It seems that speakers perceived both fire as an active force and fire as a tamed substance.

- Note for my fellow nerds: I don’t know where to locate Tocharian in this story of gender development. It’s complicated.

Bonus fun fact

The word gender, liberally used in this article, comes from Latin genus, which just meant ‘type’. Genus is also the origin of general and generic. What marks gender out from the other offspring is its D. This isn’t etymological; it’s epenthetic. The consonant was inserted into the word by post-classical speakers after genus, specifically the oblique form genere, had become gen’re. This contained a phonetically uncomfortable sequence of tongue-tipped sounds that the extra consonant could assist with. If you’d like to read more about epenthesis, I have an article all about it to hand…

References

- Alkire, T., & Rosen, C. (2010). Romance languages: A Historical Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahl, Ö. (2000). Animacy and the notion of semantic gender. In Unterbeck, B. et al. (Eds.) Gender in Grammar and Cognition I: Approaches to Gender. II: Manifestations of Gender. De Gruyter. 99–115.

- Hockett, C. F. (1958). A Course in Modern Linguistics. New York: Macmillan.

- Hoffner Jr, H. A., & Melchert, H. C. (2008). A Grammar of the Hittite Language: Part 1: Reference Grammar. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- Kim, R. I. (2009). The feminine gender in Tocharian and Indo-European. In Yoshida, K., & Vine, B. (Eds.) East and West: Papers in Indo-European Studies. Bremen: Hempen. 69–87.

- Kim, R. I. (2014). A Tale of Two Suffixes: *‑h2‑, *‑ih2‑, and the Evolution of Feminine Gender in Indo-European. In Neri, S., & Schuhmann, R. (Eds.) Studies on the Collective and Feminine in Indo-European from a Diachronic and Typological Perspective. Leiden/Boston: Brill. 115–136.

- Ledo-Lemos, F. J. (2003). Femininum Genus: A Study of the Origins of the Indo-European Feminine Grammatical Gender. München/Newcastle: LINCOM Europa.

- Luraghi, S. (2009). The origin of the feminine gender in PIE. Grammatical Change in Indo-European Languages. Amsterdam, Philadelphia.

- Luraghi, S. (2011). The origin of the Proto-Indo-European gender system: Typological considerations. Folia linguistica 45(2). 435–464.

- Melchert, H. C. (2014). PIE*-eh2 as an ‘Individualizing’ Suffix. In Neri, S., & Schuhmann, R. (Eds.) Studies on the Collective and Feminine in Indo-European from a Diachronic and Typological Perspective. Leiden/Boston: Brill. 257–272.

- Ringe, D. (2017). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Images my own, from Wikimedia, or from credited sources. Cover image: woodcut print from 16th-century Germany, in the care of the British Museum.

Wonderfully written!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful article. Do you have any insight into how some Indo-Aryan languages that maintain grammatical gender (e.g. Hindi-Urdu) fit loanwords into the gender categories? In particular for inanimate objects? For example, as a native Hindi speaker, to say that “The lift [i.e. elevator] is empty” in Hindi, I would say “Lift khali hai”, where khali takes the female ending.

LikeLiked by 1 person