Delighted and motivated by the positive response to my recent article, Greek, the Asian and African Language, my mind has been occupied by an eagerness to share another example of historical languages turning up where we don’t expect them to be.

That post and this one are united by an appreciation of how interconnected the ancient world was. True, travel could be dangerous and laborious (a fact perhaps reflected in the etymology of the word travel itself, a sister of French travail ‘work’). It certainly did not progress at the consistent speed of a modern car, train or plane.

Nonetheless, people did move around, and they took their languages along for the ride. One result of their peregrinations is that languages can pop up in the historical record in surprising locations.

To make it into that record is by no means guaranteed. What few texts and witnesses to ancient language have come down to us must surely reflect only a fraction of the speech of their day. Political prestige is a factor in their endurance; if a society’s elite patronised a language, it stood a good chance of being committed to the medium of writing.

While Greek, the Asian and African Language was partly concerned with Greek’s success to the east, the star of this Part 2 is a language that met with social success far to the west of its associated region (India). It makes a brief appearance in ancient sources that continues to intrigue historians and linguists alike. Well, at least one of them.

First, though, here’s a lot of necessary (but no less interesting) linguistico-historical background.

Among the Aryans – no, not those ones

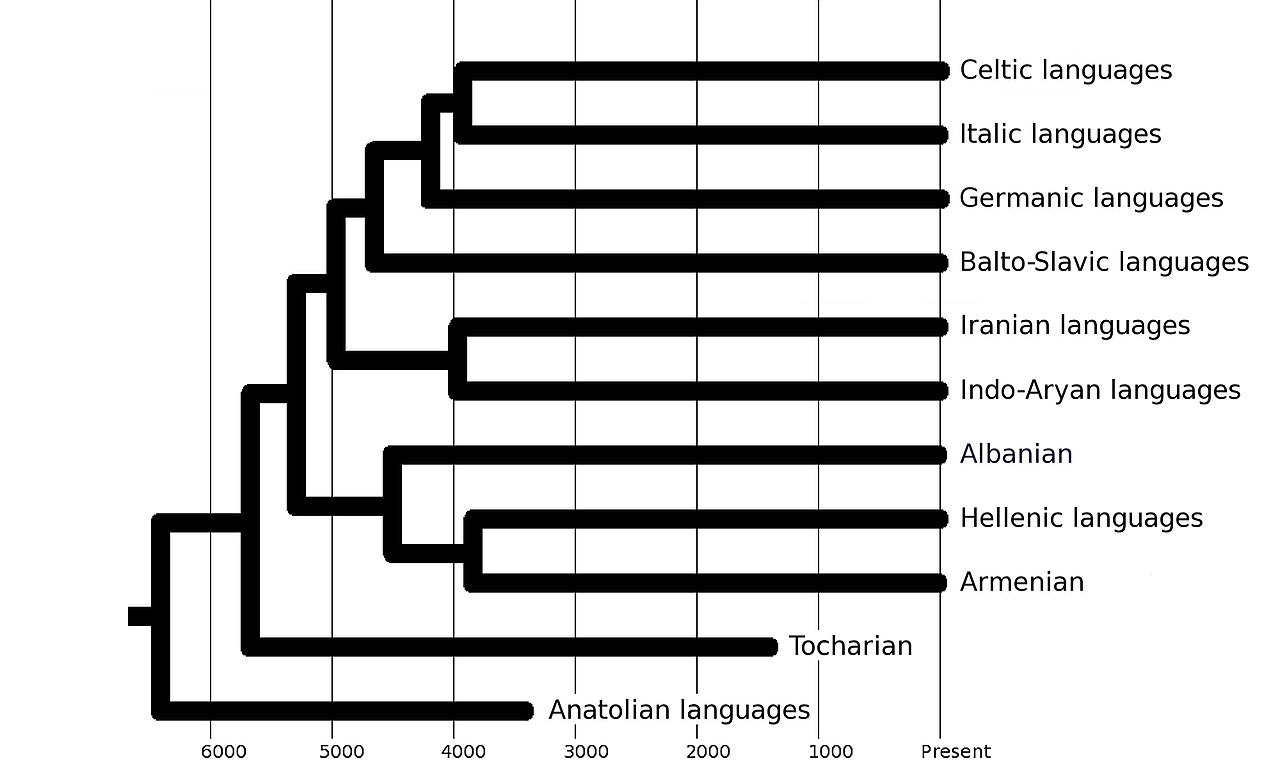

A sizable chunk of my adult life has been spent in the company of one particular group of languages, a family of sisters and cousins that share a prehistoric grandmother, and now encircle the world. This is the Indo-European family of languages. It gets its name from the distribution of its members, scattered across a broad sweep of Eurasia, prior to further enlargement by European powers in the early modern period.

It was during that same period that the recognition of the languages’ relationship began to occur, thereby connecting Gujarati to Greek, Sinhala to Swedish, Persian to Portuguese. In particular from the late 18th century onwards, the Indo-European family established itself as an object and field of study, and it has since blossomed into a rich garden of language and history.

Among the branches of the Indo-European family tree that scholars have perceived, there are subordinate Indo-somethings. While Indo-European refers to the whole set, Indo-Iranian is a subset of those languages. This is one of the primary branches of the tree as we understand it; it’s comparable in that status with the Germanic branch to which English belongs.

Within Indo-Iranian, Iranian and Indo-Aryan are then two sub-subsets. Each subsequent set has its own ancestral nexus point, and branches out from it like roots. Each emerged through the natural process of linguistic splitting, through which accents, dialects and full-blown languages are born.

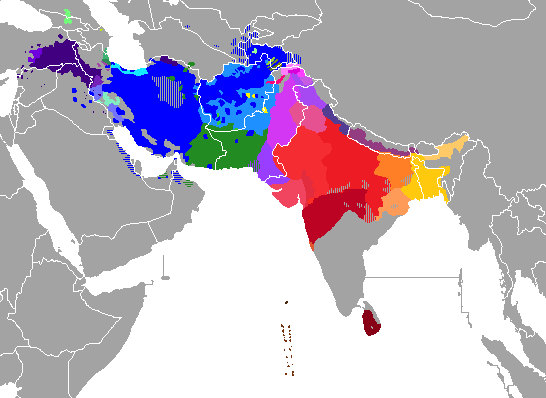

But make no mistake; Indo-Iranian may be one step subordinate to Indo-European, but the term covers a cosmos of languages. From Kurdish in the west to Assamese in the east, Indo-Iranian is a major grouping in its own right.

As said, the central divide within Indo-Iranian is into Iranian and Indo-Aryan languages. Yes, dear language nerds, there are also the Nuristani languages, but I will set them and their place in the story to one side.

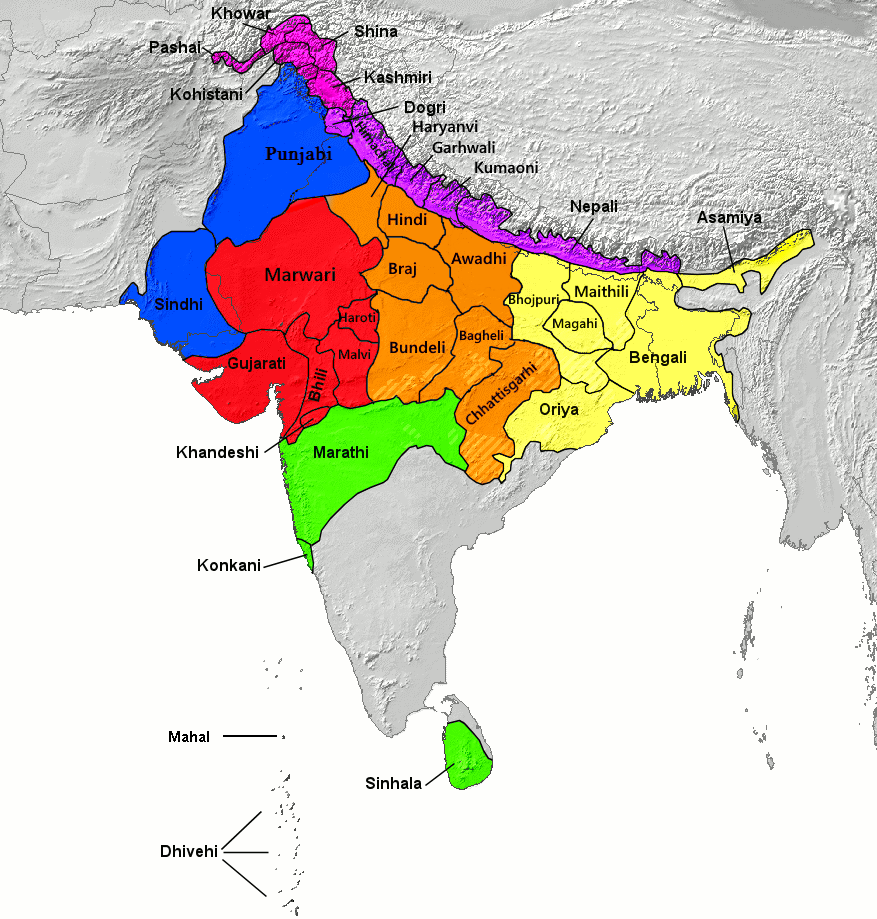

The first of the two major sub-subsets contains Persian, Pashto, Balochi and beyond. The second contains the linguistic cornucopia spoken and written across Pakistan, north and central India, Bangladesh, and up into Nepal; it includes major languages like Hindi-Urdu, Bengali, Marathi and Punjabi, each with speakers numbering in the millions.

Now, some readers may raise an eyebrow or furrow a brow at the use of the term Aryan with such abandon. For sure, the term was weaponised to evil ends in 20th-century Europe. Yet its use in that century and continent make up only one chapter in its long employment. It has its origins far away from Europe, in the northern reaches of prehistoric Central Asia.

Its journey from there to the posters and pages of Nazi propaganda was made possible through a combination of academic scholarship and twisted logic. European ‘experts’ of the 19th century seized on the term as a signifier of an ancestral superior people, and concurrently a racial category that could exclude as much as include. They hijacked and perverted an ethnic term that still has currency in Asia today.

The word Aryan is in fact cognate with Iranian. The two go back to a single identity self-applied in the Central Eurasian Steppe. Its etymology is much debated, but the reconstructed etymon *Áryas seems to have referred to a member of a people who lived, died and rode chariots on either side of the year 2000 BC.

“The original homeland of the Aryans, the speakers of Common Indo-Iranian, cannot be precisely identified, but is thought to have been in western Central Asia, to the east and north-east of the Caspian Sea.”

(Sims-William 1998: 127)

From the linguistic and archaeological artefacts they left behind, we can sketch the vague outline of the actual Aryans. They shared an Indo-European language, a semi-nomadic pastoralist lifestyle, and a sophisticated understanding of the supernatural. Their gods constituted a complex pantheon, among them still famous names like Mitra and Indra. Centuries later, Mitra would find favour across the Roman Empire, venerated through the mysteries of Mithraism.

The common language of the Aryans (‘Proto-Indo-Iranian’) would go on to split, split and split again. Over the course of the second millennium BC, migration in two general southwest and southeast directions would gradually motivate the ancient divide into Iranian and Indo-Aryan. Iranian languages would end up in Iran, unsurprisingly, but also all along the vast east-west Steppe. The Scythians and Sarmatians of the classical era seem to have spoken Iranian tongues. Meanwhile, Indo-Aryan would end up in India. On the journey and at their destinations, each would continue to burgeon into today’s dense canopy of languages.

That linguistic disintegration would’ve gone hand in hand with the dilution of the label of *Áryas and its importance. That said, it has retained relevance; in as late as 1935, Reza Shah Pahlavi asked the rest of the world not to call his country Persia, but rather the local name Iran (etymologically ‘of the Aryans’). The rest of the world listened.

The hyphenated term Indo-Aryan is intended to acknowledge the linguistic heritage that the languages under its wing share with Iranian languages, but not with all the languages of India. That country and its neighbours are home to other big language families, like Dravidian. With the exceptions of Sinhala and Dhivehi, Indo-Aryan languages generally find themselves to the north of Dravidian ones within South Asia. This modern-day spread points to their prehistory away to the north, in the Eurasian Steppe.

Supporters of the term Indo-Aryan would argue that its ‘Indian-but-not-all-India’ quality is an essential aspect that the alternative label Indic struggles to convey and distinguish.

When you look at the early samples of language from either side of the Iranian/Indo-Aryan division, their inherited linguistic and cultural affinity is clear. Representing the Iranian side, we have Avestan, the language of the corpus of Zoroastrian literature known as the Avesta. For Indo-Aryan, we have Vedic (also called Sanskrit and Vedic Sanskrit, but I lean towards plain Vedic). This was the language behind great religio-literary compositions like the Rigveda, rich in hymnal praise of the gods.

By the second half of the second millennium BC, Iranian and Indo-Aryan speech had clearly developed into two distinct daughters of Proto-Indo-Iranian. However, from what our surviving sources witness, the two traditions of Zoroastrian and Vedic verse nonetheless still shared so much in terms of sounds, words, grammar and gods.

On the language side, we can find words that are more or less still the same. Numbers, for instance, remained fairly united; five was paṇca for Avestan speaker-writers, and páñca- in Vedic. Yet deeper disagreements had already emerged too; the number one is a lexical faultline: aēuua- in Avestan, but *aika- for the Indo-Aryan speakers composing the Vedas.

In between concord and discord, we also find many correspondences – that is, consistent differences, each with a common origin. For example, Avestan shows a /h/ sound where Vedic has a /s/. An Avestan speaker would count seven things with the number hapta, a Vedic speaker with saptá-. The former would include themselves with ahmī ‘I am’, the latter with ásmi. In this aspect of phonology, the Iranian /h/ is the innovative sound, the Indo-Aryan /s/ the conservative.

For another example of this, the Rigveda often mentions and praises soma, a powerful ritual drink of unclear botanical origin. A whole mandala (‘book’, for want of a better word) of the Rigveda is devoted to it.

ápa soma mŕ̥dho jahi / áthā no vásyasas kr̥dhi

‘Drive away enemies, soma, then make us better’

(Rigveda 9.4.3)

At or around the time, the composers of the Avesta were likewise fairly fond of the sacred plant haoma.

āat̰. aoxta. zaraθuštrō. / nəmō. haomāi. / vaŋhuš. haomō. / huδātō. haomō.

‘Then Zarathustra said: reverence to haoma, haoma is good, haoma is well formed’

(Hōm-Yašt 16)

These ancient characters and substances remained so potent that they inspired European writers of the 19th and 20th centuries; Nietzsche adopted the central figure of Zoroastrianism for his 1880s book Thus Spoke Zarathustra, while soma gave its name to the infamous drug in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel Brave New World.

Among the gods, a curious kind of divine inversion occurred that upset the original Aryan religious cosmology. Different types of deity, who presumably once all lived in relative harmony, could either ascend further or be cast down.

In the Zoroastrian hymns and their Avestan language, a daēuua- is a demon and an adversary. Meanwhile, ahura- is an honorific meaning ‘lord’, as bestowed on the Zoroastrian supreme being, Ahura Mazda. Contrarily, in Vedic religion, the cognate devas come to be the good guys, and asuras the ones to avoid. For example, Indra, king of the devas, is a deity supremely exalted in the Rigveda.

índraṃ vayám mahādhané / índram árbhe havāmahe

‘Indra we call on in the great battle, Indra we call on in the small battle’

(Rigveda 1.7.5)

Meanwhile, the Indra of the Avesta is a second-rank demon, and barely mentioned.

paiti. pərəne. iṇdrəm.

‘I charge against Indra’

(Vidēvdād 10.9)

Society and divinity were splitting along the same faultline as language, and the shifting status of these divine species is actually detectable in our sources. Composed over centuries before its final consolidation, the Rigveda is built up of discernible layers of belief. Textual archaeology can excavate the rise of the devas and the fall of the asuras from within its thousands of verses. This emerging disagreement has been explained as the product of reform, with one if not two movements seeking to change the original Aryan religion from within.

Out of all this language, prehistory and religion, what I’d have you bear in mind is that Indo-Iranian is a big group of historical and current languages, divisible into Iranian and Indo-Aryan sets. All of them were once one language; their common ancestor, which we call ‘Proto-Indo-Iranian’, was itself an early member of the Indo-European family tree. It broke up through the migration of its speakers.

Speakers of Iranian-to-be walked or rode south and west, both along the Steppe and towards what is today Iran. Speakers of future Indo-Aryan headed south and east, descending from the mountains into South Asia. This gives us the general distribution of the two today, with the former to the west of the latter. Indo-Aryan languages are understandably closely associated with India, hence the name.

This linguistico-historical background makes it all the stranger that our earliest evidence for the Indo-Iranian family (specifically from its Indo-Aryan branch) actually comes from the Middle East.

Horse riders can go far

D.MESMitrassil D.MESArunassil DIndara D.MESNasattiyanna

‘… both Mitra and Varuṇa, Indra and the Nasatya …’

(KBo I 3 Vo 24)

A treaty in c. 1400 BC invoked these gods as its guarantors. They were top gods in the ancient Aryan pantheon, and have been venerated in India for millennia now. Mitra and Indra we have already met, and they all appear together, in the same order, in the Rigveda:

ahám mitrā́váruṇobhā́ bibharmi / ahám indrāgnī́ ahám aśvínobhā́

‘I bear Mitra and Varuṇa both, Indra and Agni, and the Aṣvins (a.k.a. Nasatya) both’

(Rigveda 10.125.1)

But this treaty wasn’t unearthed in India; it was found in what is now Turkey.

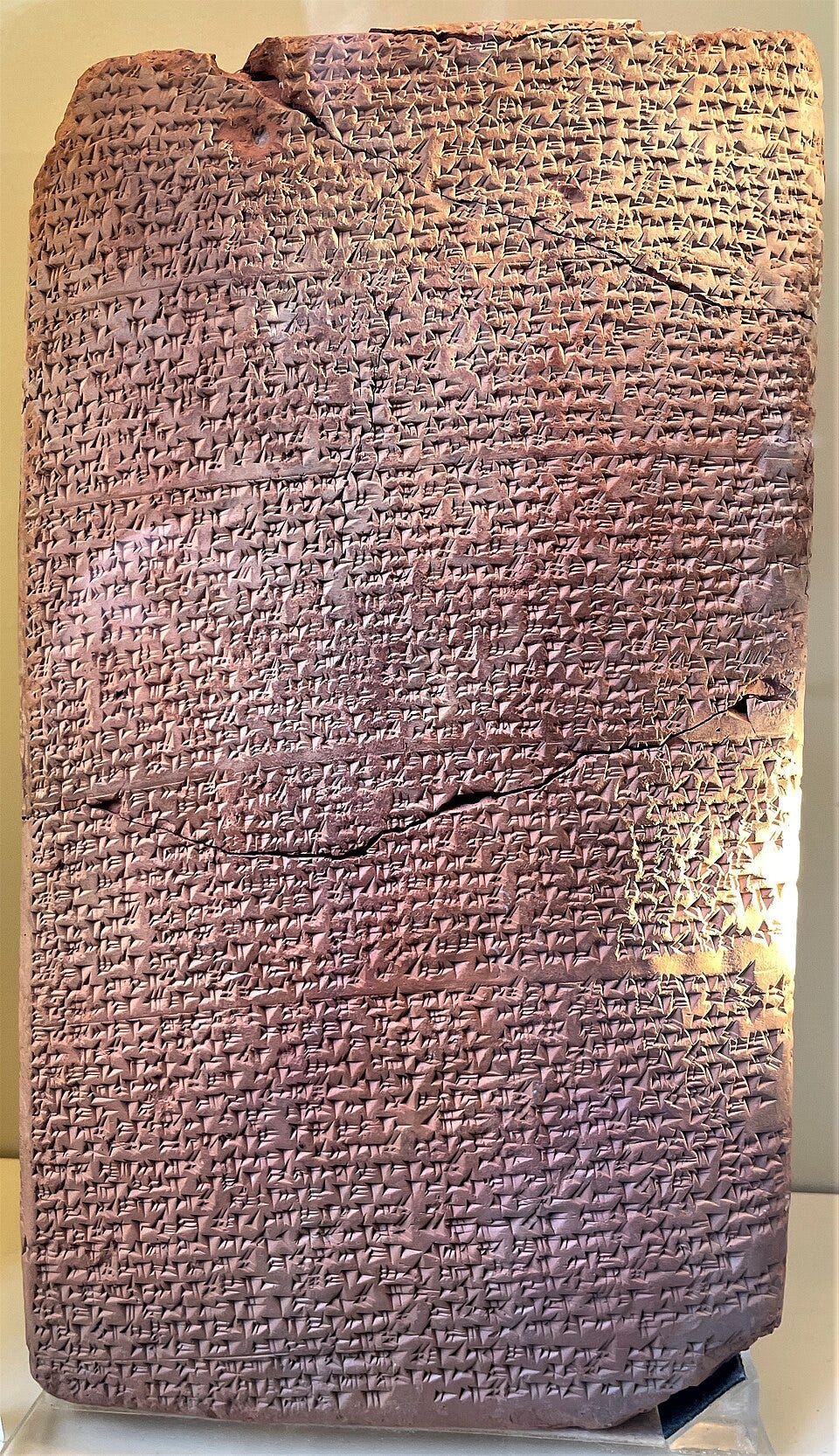

The treaty committed to clay a new-found harmony between the Hittites and Mitanni. While the Hittites were found in the 1910s to have spoken an Indo-European language (like a niece of Proto-Indo-Iranian), most people in Mitanni spoke Hurrian. This was a non-Indo-European language of northern Mesopotamia, written in the widespread cuneiform system.

Mitanni was established as a kingdom around the year 1500 BC, covering a large territory today torn between the countries of Syria, Turkey and Iraq. While no doubt a linguistically dynamic people – as humans historically have tended to be – the majority in Mitanni seem to have been native Hurrian speakers. For that reason, we might expect the kingdom’s elite to have likewise been Hurrian in speech, writing and outlook, give or take some external influences from local superpowers like Egypt.

Instead, what we find is a heavy linguistic influence from Indo-Aryan. This is in fact our earliest evidence for the Indo-Aryan family, and the bigger Indo-Iranian branch to which it belongs. Far away from India and the Central Eurasian Steppe, Mitanni texts bear witness to a cultural layer imposed on the general Hurrian population.

Kings and gods form part of this ‘superstratum’; in addition to invoking gods like Indra, the kings of Mitanni style themselves with regnal names that are discernably Indo-Aryan in their etymology. These are names refracted through the cuneiform tradition of writing, which can make recognition a little uncertain, but the name recorded for king Tushratta, for one example, has been derived from the Indo-Aryan word tveṣárathaḥ. This means ‘quick-chariot-ed’, and is again a word that appears in the Rigveda (5.61.13). Tushratta was an ally of the Egyptian New Kingdom and father-in-law to the radical pharaoh Akhenaten. His messages were found among the Amarna corpus of official letters from Upper Egypt, which was even further for an Indo-Aryan word to travel.

Heck, it’s been proposed that the name Mitanni itself has an Indo-Aryan origin. But beyond kings, states and gods, everyday words from Indo-Aryan also appear. The kingdom relied on a class of chariot-driving young warriors, known as maryannu. This term, documented in sources from both Mesopotamia and the east coast of the Mediterranean, has been derived from Indo-Aryan márya-. This means ‘young man’ in the Vedas, but a shift in meaning to ‘warrior’ is not implausible. We can imagine young men making a name for themselves through their skillful operation of the ancient world’s equivalent of a tank.

Chariots and horses are a common theme in the fragments of Indo-Aryan language of Mitanni. Kikkuli, a Hurrian individual whose name we actually know, left us a delightful document that shares his equine expertise. Beginning “thus speaks Kikkuli, master horse-trainer of the land of Mitanni”, Kikkuli’s guide discusses not only how to get horses to follow your orders, but also how to care for their needs.

It was written in c. 1345 BC in the Hittite language, yet contains several words of Indo-Aryan origin. Apparently these came with the whole tradition of horsemanship, and Kikkuli was unable to translate them properly with single Hittite words.

In his text, we find the numbers aika– ‘one’, tera- ‘three’, panza– ‘five’, satta– ‘seven’, na[ua]- ‘nine’, each in combination with a word for ‘turn’ or ‘circuit’, –u̯arttana. Compare these numbers with their equivalents in Classical Sanskrit: éka-, trí-, páñca-, saptá- and náva-. The job title that Kikkuli introduces himself with (“aššuššanni”) may also contain the Indo-Aryan word for ‘horse’ (in Sanskrit: áśva-). We can assume that Kikkuli was rewarded for his service to the Hittites, although I do wonder if teaching them Mitanni horsemanship constituted a kind of treason.

Since Indo-Aryan and Hittite were both ultimately Indo-European languages (albeit greatly separated by time), Kikkuli’s manual displays a rare meeting of two ancient members of the family, like two branches of the same tree crossing over in the forest.

What we have here is a prestigious elite language of the Mitanni kingdom, whose speakers, at some point, must have travelled a considerable distance to bring it close enough to Hurrian lands. It also seems to have come with a culture attached, or at least a tradition of prowess in horsemanship and exceptional hippological knowledge. We’ll get to what social circumstances might have made Mitanni Indo-Aryan possible in a moment, but first, a word on that distance.

If we accept that these interloping words in our Mitanni texts are indeed Indo-European, and specifically Indo-Iranian in origin, why not derive them from an early Iranian language? Why Indo-Aryan, when Iranian speakers ultimately travelled and settled westwards? In proposing contact with the Indo-Aryan branch, we have a greater distance to account for. Yet that’s what the linguistic evidence points to.

As mentioned above, differences emerged between Iranian and Indo-Aryan, and what words we have from Mitanni identify themselves as from the latter. The number one, for example, is aika-. Remember that this is a hard line of disagreement. Iranian languages have a primary numeral with an internal /w/ sound – for example, Avestan aēuua-. It’s Indo-Aryan that is team K. Moreover, satta- for ‘seven’ preserves a /s/ sibilant, rather than an Iranian /h/.

Beyond the sounds of the words from Mitanni, their reference is noteworthy too. The appearance of Varuṇa in the invocation above aligns it with the Vedic religion and their deities; Varuṇa is prominent in the Rigveda, but absent from the Avesta.

Yes, the divergence of language and people is complicated, but the accumulated evidence indicates an early kind of Indo-Aryan as the donor of this vocabulary, even though Indo-Aryan would end up in the east. Strange to say, it overtook Iranian, appearing in the historical record to both its sister’s east and its west.

In terms of linguistic history, we can at least say from the evidence that Mitanni’s contact with that language happened after the break-up of Indo-Iranian. But it is very hard to say where its speakers had travelled from to come close to Mitanni. The Indo-Aryan language might be closely associated with India, but that does not entail that India (even maximally defined) was the geographical starting point for this linguistic contact. Some scholars have stated that “the Indo-Aryans of the Mittanni most probably were never in India” (Lubotsky and Kloekhorst 2021: 331). Instead, they might have set off from somewhere to the northwest, somewhere closer to the Hindu Kush, like Bactria.

Nonetheless, wherever they started, it was still rather a long way from there to the banks of the river Tigris. Who then were these people, whose language and culture met with such success in Mitanni?

Of course, there is more than one plausible explanation for this meeting of languages in antiquity. One, a ‘maximal’ view, is that Mitanni was “dominated by an Aryan aristocracy” (Lazzeroni 1998: 98). In other words, Aryans arrived in person from the east, and through conquest, diplomacy, alliance or matrimony ended up ruling the Hurrian-majority kingdom. I note that the Britannica article goes as far as to say that Aryans founded the whole kingdom of Mitanni.

Archaeology and genetics demonstrate that they would’ve come too late to introduce the domestication of the horse to the Middle East, but they may have had outstanding equine skills that gave them a military and political edge. The chariot may have been their specific field of expertise.

This scenario, I think, accords with the linguistic evidence pretty well. A language needs to be backed up by some serious social currency to become the medium for naming kings and invoking the gods. Historical evidence too leans towards an active inequality in language and people in Mitanni, in how those gods were addressed:

“The order in the invocations of deities is telling: Akkadian first, Sumerian second, Mitanni Aryan next, Hurrian last. This implicit textual hierarchy actually supports the idea that Mitanni Aryan was in a position of socio-cultural superior prestige when compared to Hurrian in the eyes of Hurrian people themselves, who made up the majority of the inhabitants of the Mitanni Kingdom.”

(Fournet 2010: 5)

Yet there are ‘minimal’ explanations, which afford the Aryans and their Indo-Aryan language only a small or indirect role in the affairs of Mitanni. Under this view, the exchange of words and ideas was lighter, more partial and probably a lot less turbulent.

It may have happened in Mitanni, perhaps with a small contingent of advisory Aryans serving as experts in new technology and new deities. Alternatively, the point of contact could have occurred elsewhere, or via a chain of transmitted knowledge that began somewhere between Mitanni and India.

Instead of a living culture, Indo-Aryan technical terms such as we find in Kikkuli’s manual may have been “piously handed down as fossils” (Kammenhuber 1988: 788), acquired by the Hurrians and then the Hittites as opaque jargon. It’s true that these words are few in number and are fully plugged into local Hurrian grammar. They therefore may not “reflect the presence of speakers of Indo-Aryan, rather they are relics of interaction with Indo-Aryan speakers” (von Dassow 2008: 85).

For myself, if I can humbly offer up an opinion, I bend towards the maximal view. For a people to provide the name of an ancient kingdom, and to furnish it with gods, royal names and an elite class of warriors, I cannot see how the Aryans could not have been a powerful personal presence among the Hurrians. They may have been linguistically assimilated by the time of our evidence for their Indo-Aryan language in Mitanni, but the nature of that evidence speaks to me of at least some direct contact between Aryans and Hurrians.

If I’m right in that, then we have here a prime instance of the interwoven fabric of antiquity. Set aside a stale image of stagnant populations stubbornly sticking to their lands and settlements; the ancient world can surprise us with its dynamism. Societies were interacting and overlapping in ways that required considerable means and determination. Now, here in the present day, I’m keen to fly the flag for language as a way to unearth that impressive past.

END.

Note:

Words prefixed with an *asterisk are hypothetical words, not directly witnessed by historical sources, but still very likely to have existed. Words suffixed with a hyphen- designate incomplete stems, without the grammatical endings necessary for their use in a sentence.

Non-linked references:

- Fournet, A. (2010). About the Mitanni Aryan Gods. Journal of Indo-European Studies 38(12). 26–40.

- von Dassow, E.,(2008). State and society in the late Bronze Age: Alalaḫ under the Mittani Empire. In Owen, D. I., & Wilhelm, G. (eds.), Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians, vol. 17. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press.

- Hrozný, B. (1931). L’entraînement des chevaux chez les anciens Indo-Européens d’après un texte Mitannien-Hittite provenant du 14e siècle av. J.-C. Archiv Orientální 3(3). 431–463.

- Kammenhuber, A. (1988) On Hittites, Mitanni-Hurrians, Indo-Aryans and Horse-Tablets in the 2nd Millennium B.C. In HRH Mikasa, T. (ed.), Essays on Anatolian Studies in the Second Millennium B.C. 35–51. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Lazzeroni, R. (1998). Sanskrit. In Ramat, A. G., & Ramat, P. (eds.), The Indo-European Languages. 98–124. Routledge.

- Lubotsky, A. (2023). Indo-European and Indo-Iranian Wagon Terminology and the Date of the Indo-Iranian Split. In K. Kristiansen, G. Kroonen, & E. Willerslev (eds.), The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics. 257–262. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lubotsky, A., & Kloekhorst, A. (2021). Indo-Aryan -(a)u̯artanna in the Kikkuli treatise. In H. Fellner, M. Malzahn, & M. Peyrot (eds.), Lyuke wmer ra: Indo-European Studies in Honor of Georges-Jean Pinault. 331–336. Ann Arbor NY: Beech Stave Press.

- Martínez García, F. J., Vaan, M. D., & Sandell, R. (2014). Introduction to Avestan. Leiden: Brill.

- Parpola, A. (2015). Early Indo-Iranians on the Eurasian Steppes. The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and The Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press.

- Raulwing, P. (2009). The Kikkuli Text. Hittite Training Instructions for Chariot Horses in the Second Half of the 2nd Millennium B.C. and Their Interdisciplinary Context. From here.

- Sadovski, V. (2009). Ritual Formulae and Ritual Pragmatics in Veda and Avesta. Die Sprache 48(1). 156–166.

- Sims-Williams, N. (1998). The Iranian Languages. In Ramat, A. G., & Ramat, P. (eds.), The Indo-European Languages. 125–153. Routledge.

Sources:

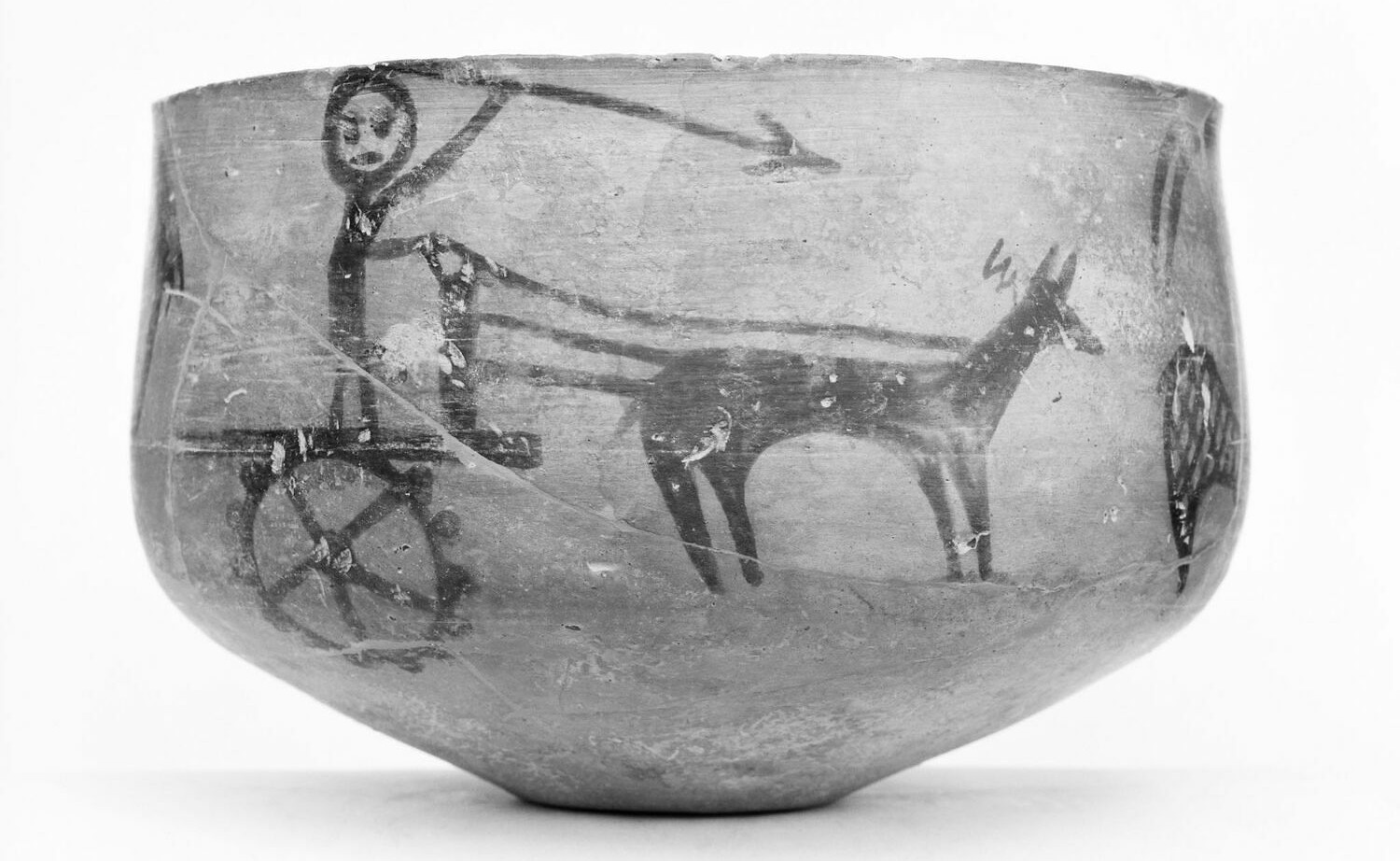

Images my own, from Wikimedia, or from credited sources. Cover image: a decorated bowl from Iran, dated to 2000-1800 BC, on display at the Louvre.

What a great read, once again. Thanks!

Two associations:

LikeLiked by 1 person