Just as the borders of Europe are geographically, politically and socially fuzzy, so too are its linguistic edges. Whatever lines of demarcation we care to draw, the many flavours of speech to be heard in Europe flow over those lines like the air of which they’re made.

Consequently, a label like ‘a European language’ is to be used with a pinch of caution and a proviso or two. This is all the truer in the modern era, when colonial expansion has transported and transplanted European languages, such as English and Spanish, to other continents. Can English be straightforwardly called ‘a European language’, for example? History might say yes, but the present-day distribution of its speakers would argue back. Even long before our own day, certain languages could not be contained by a single landmass. The Greek language offers a rich example.

Greece, Greeks and Greek – today, country, people and language alike all feel securely European in location, identity and outlook. Testifying to its European-ness, the Greek language holds official status not only in the modern countries of Greece and Cyprus, but also in the European Union, to which those countries belong. It appears on European money too, as “EYPΩ” on euro notes.

Brushing over the question of what larger geographical unit we assign Cyprus and south-of-the-Green-Line Cypriots to, the Greek speakers of the Old World are largely concentrated on territory that we can comfortably call Europe. All of this is no wonder, considering that we get the term Europe from Greek.

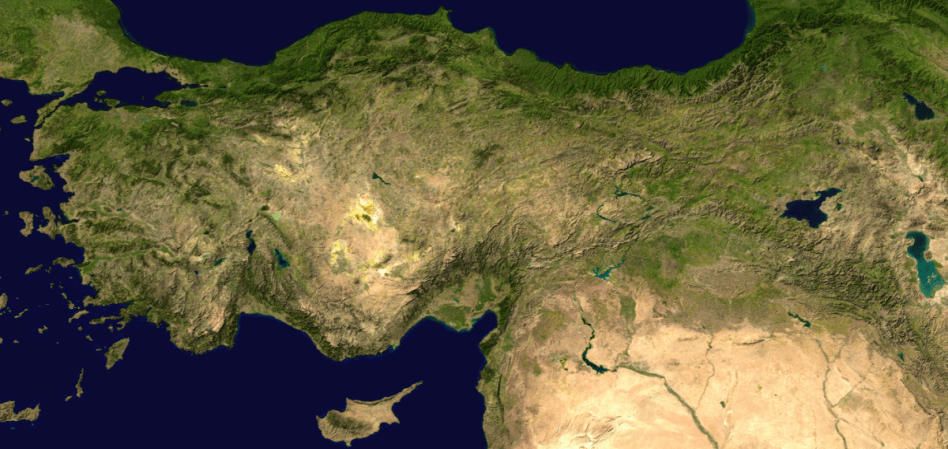

The territory of Greece today comprises the mainland at the bottom of the Balkans and thousands of islands strewn across the Aegean and Ionian Seas. On this basis, you’d be forgiven (by me, but perhaps not by the Greeks) for thinking that the language has never wandered too far from this Hellenic heartland. Quite the opposite is true, and so much of its historical usage and cultural achievements have happened outside of Europe.

The purpose behind this post is to foreground that linguistic history, to re-introduce Greek to you as a language not just of Europe, but of Asia and Africa too. It can lead us into a world of extra-European speech and writing, as the language was passed on to peoples beyond the borders of a Greek identity, even generously defined. To begin this exploration, we, like Odysseus himself, first have to head east and make land on the shores of Anatolia.

A Language of Asia

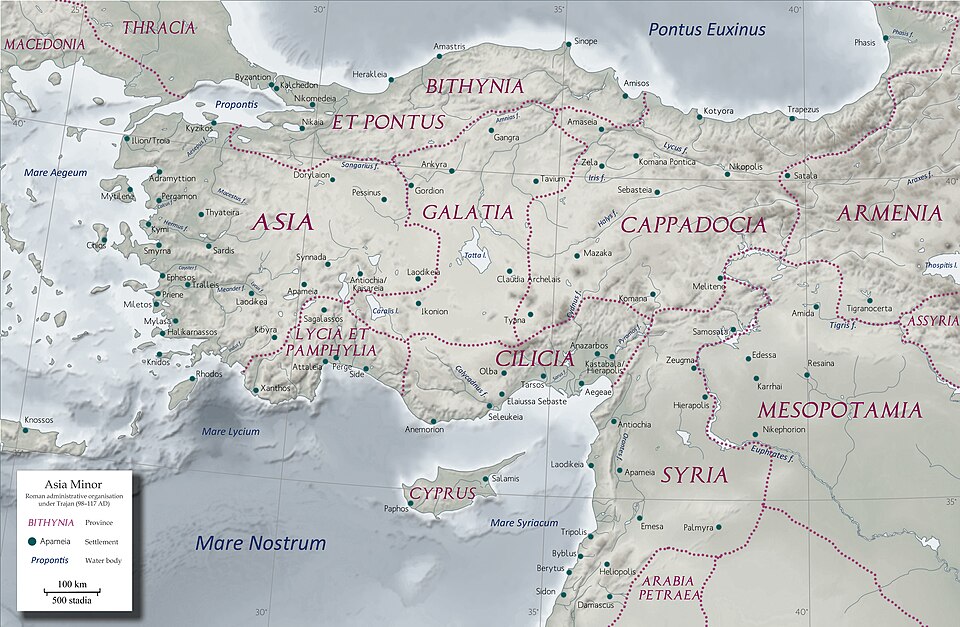

Once upon a time, Asia was a much, much smaller place. The term Asia has ballooned in its designation over the millennia, increasing in size to include regions (and the peoples living in them) far to the east of its earliest reference point. This was the western edge of Anatolia and the eastern coast of the Aegean, today part of Turkey.

The word seems to have been a foreign acquisition by the Greeks; something like it first appears in Hittite sources (as “A-as-su-wa”), and then in the Linear B script that wrote down Mycenaean Greek (as “A-si-wi-ja”). Originally, when Greeks of the archaic and classical eras wrote the term Ἀσία, what they had in mind was the region of Lydia, western Anatolia, or Anatolia in general. This segment of the world’s map can still be referred to as Asia Minor. ‘OG Asia’ might also be historically appropriate. The Romans, who took control of it in the 2nd century BC, maintained the narrower meaning in their province of Asia.

However, there are hints of the world-striding landmass already in the classical era. The historian Herodotus thought of the world’s land in terms of three broad continents: Europe, Asia and Libya (Africa). The second extended pretty far east in his estimation.

“Πέρσαι οἰκέουσι [Ἀσίην] κατήκοντες ἐπὶ τὴν νοτίην θάλασσαν τὴν Ἐρυθρὴν καλεομένην … μέχρι δὲ τῆς Ἰνδικῆς οἰκέεται Ἀσίη. τὸ δὲ ἀπὸ ταύτης ἔρημος ἤδη τὸ πρὸς τὴν ἠῶ, οὐδὲ ἔχει οὐδεὶς φράσαι οἷον δή τι ἐστί”

“The Persians inhabit [Asia], reaching to the southern sea called the Red … As far as India, Asia is inhabited. But after this, desert is to the east, nor can anyone say what kind of land is there.”

(Herodotus, Histories 4.37,40)

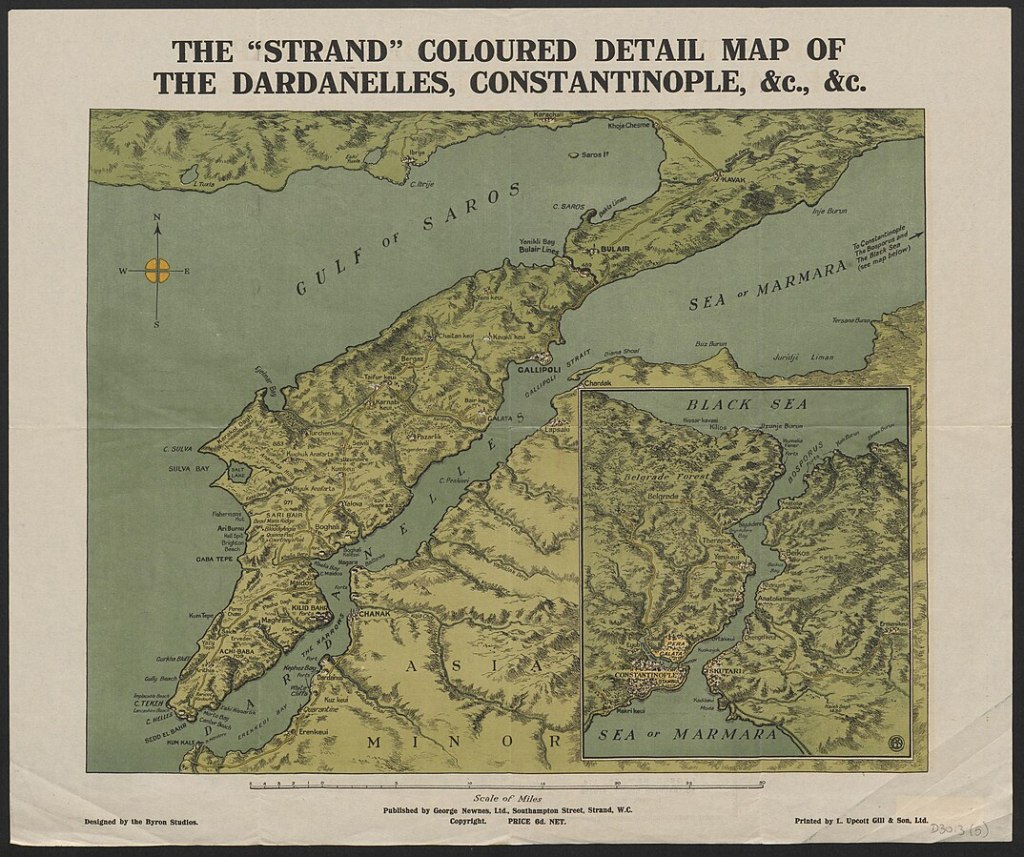

The fault-line between Europe and Asia ran through the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, the slim straits that link the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Looking across the waters from the western side (the European perspective), Asia could easily roll on to the world’s end, and the geographical label could grow as far as ancient knowledge of it permitted.

The ancient Greeks, mind you, were not going to be penned in by a mere sliver of water like the Dardanelles. They could be found on both sides of the Aegean. Up and down the west coast of Asia Minor, the migration of Aeolian, Ionian and Dorian colonists enlarged the definition of Greece.

Though these cities of Asia may have been secondary settlements for the Greeks, they achieved great prestige and cultural weight. Three of the seven wonders of the ancient world were on the Asian side of the Aegean. Herodotus himself (born c. 485) came from Dorian-developed Halicarnassus, famed for its mausoleum, and now entombed by the Turkish city of Bodrum. Tradition says that Homer, the supreme Greek poet and the inspiration of so much European literature, lived and composed in the Asian region of Ionia. For people to the Greeks’ east, Ionia became synonymous with all Greece; Ionia is in fact the origin of the word for ‘Greece’ itself in many languages today: see Turkish Yunanistan, Hebrew יוון (Yavan), and Persian یونان (Yūnān).

The Greek population in Anatolia survived and thrived through the subsequent medieval and modern periods, right up to the aftermath of the First World War. The language prospered in Anatolia, a key part of the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantine, if you prefer). After this state gave up the ghost in 1453, the conquering Ottoman Empire ruled over the substantial ‘millet’ of Greek speakers in Anatolia, until that empire’s final dissolution in 1922. The Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and localised massacres of civilians then triggered an exodus of Greeks from the emerging Turkish state; the cataclysm culminated with the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Refugees from one country were made official in the other, and thousands more were ‘encouraged’ to leave. So ended centuries of Turkish life across the Balkans and Greek life in Asia Minor.

That said, the categories of Turk and Greek were determined primarily by religion: Sunni Islam vs. Orthodox Christian. Communities of Greek-speaking Muslims were exempt from the population transfers. Greek can still be heard among them today. On the southern coast of the Black Sea, in Trabzon Province, you can find people praying in mosques yet speaking Greek – Pontic Greek, to be precise, also known as Romeyka.

This endangered dialect has many noteworthy features; being outside the confluences and confusions of the Balkan linguistic zone, Romeyka preserves gems of ancient grammar lost from standard Modern Greek, like the infinitive form of verbs.

After crossing the Dardanelles, we need not travel too far to find the Greek language waiting for us on the Asian side. This should be unsurprising, given that it was in Greek that the whole concept of Asia was nurtured. The language once wrapped itself around the coast of Anatolia, but later movements of people and politics cut up that wrapping and left Romeyka stranded as an island of speech.

Another such island, long since submerged by subsequent waves of language and culture, lay much further to the east, in sight of the Himalayas.

In the 320s BC, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army broke upon Central Asia, pushing his lightning-quick conquests into lands now part of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Alexander was now the length of one major empire away from the Greek heartlands – specifically the Achaemenid Empire of the Persians, which he was in the final stages of destroying. We have to wonder if Alexander was surprised, as he approached the gateway to India, to find Greeks already living in the neighbourhood.

During the heyday of the Achaemenids, under great Persian kings of kings like Xerxes, communities of Greeks had been transferred to the other side of the vast empire. Some apparently went willingly. As Alexander approached, any joyous reunions between Greeks might have been short-lived. One story recounts that the day after Alexander encountered the Branchidae of Bactria (today northern Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan), he had them all put to death.

Alexander’s conquest of the region added new impetus to the Hellenisation of these Asian lands. New Greek-governed colonies were founded, many named after Alexander himself or his horse. He was Alexander the Great, remember, not Alexander the Humble. These colonies needed a religious life, and so classically columned temples were built to honour the Greek gods. The ruins of such temples at Ai Khanoum (Takhar Province, Afghanistan) were excavated in the 1960s, and a foot belonging to the great god Zeus was unearthed.

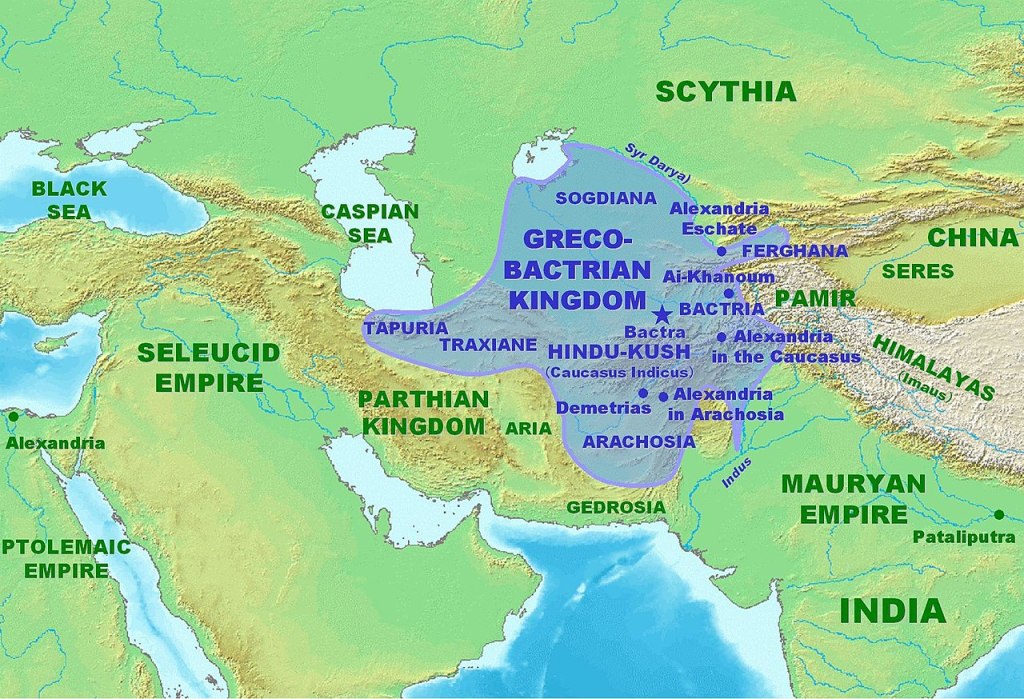

Long after the ruler of the world had departed and died, Greek successors continued to govern Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms. These were located respectively north and south of the Hindu Kush. The weight of the Greek presence swung eastwards, towards India, in the 2nd century BC, as the nomadic Yuezhi took over Bactria.

A resurgent Persia would later sever the connections between Mother Greece and her Himalayan offspring, but the Greek elites there were hardly marooned; their realms were sewn into a patchwork of surrounding cultures and kingdoms.

Their coins are a meeting of local languages with Greek, and their numismatic designs were copied by other states in Bactria and India. The Greeks’ style of sculpture for gods and heroes likely influenced the statues of Buddhism. They make appearances in Sanskrit and Pali texts – a Greek person is a Yavana in Sanskrit, and a Yona in Pali, again derived from far-away Ionia. One particular Yona, the Seleucid king Antiochus II Theos, is even mentioned in an edict of the mighty Indian emperor Ashoka the Great.

Ashoka advertised his munificence (such as his gift of medical expertise to Antiochus) through rock-cut inscriptions across his empire. Some of these are in fact written in Greek, which implies a Greek-reading audience for Ashoka. The Greek alphabet was also applied to local languages; for example, our sources for Bactrian, an Iranian language, are inscribed in its familiar letters.

One detail that the sorry story of the Branchidae includes is that they still spoke Greek, some 150 years after their migration to Bactria from Miletus in Asia Minor. If this transfer took place under Xerxes, then the Greek language arrived in Bactria sometime after the year 480 BC. Both the historical and archaeological evidence point to the vitality of Bactrian and Indian Greek at least until the line of Indo-Greek kings fizzles out in c. 10 AD.

Greek was surely one language among many in those lands, perhaps functioning as a prestigious lingua franca. Nonetheless, we have a period of Greek language in Central and South Asia spanning almost five hundred years. This is not a negligible episode of the language’s life, just an ephemeral anomaly, but rather the story of a newcomer that put down roots and contributed to an altogether different linguistic landscape.

A Language of Africa

Like Alexander’s army beside the Beas River, we should now turn back and head west. The conqueror’s successes had previously included the great prize of Egypt. Alexander had been accepted as pharaoh there in 332 BC. He ordered the construction of another city called Alexandria, although this one, on the north African coastline, has survived until today.

After Alexander’s death, his generals dismembered the empire, and Egypt ended up in the hands of his trusted officer, Ptolemy.

The Ptolemaic period of Egypt, from Ptolemy’s pharaonic elevation in 305 BC to Cleopatra’s suicide in 30 BC, cultivated a flowering of art and science. As an example, it was under the Ptolemies that the Library of Alexandria was founded and patronised, although, frankly, the importance of the library and the tragedy of its destruction(s) are greatly exaggerated. Alexandria’s intellectual life continued into the time of the city’s Roman rulers; it was home to Hypatia and the Jewish philosopher Philo. It was in Alexandria that the Hebrew Bible (to Christians: the Old Testament) was definitively translated from Hebrew into – yes, you guessed it – Greek.

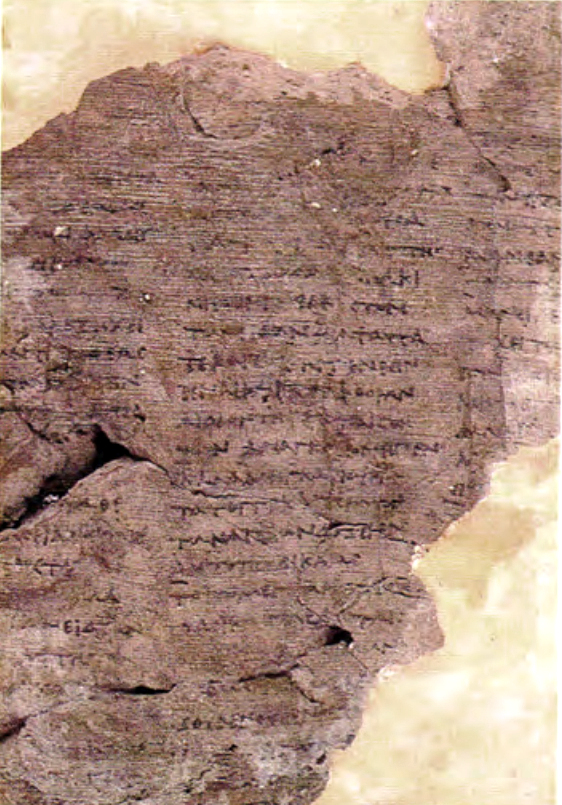

The city was a powerhouse for the language, which could unite its multinational and multireligious inhabitants. Greek was what new arrivals would have turned to to navigate the city and Egypt in general. Among my favourite finds is a papyrus phrasebook from Late Antiquity, which provided Armenian visitors to Egypt with essential Greek words and idioms, except written in Armenian letters for ease of use.

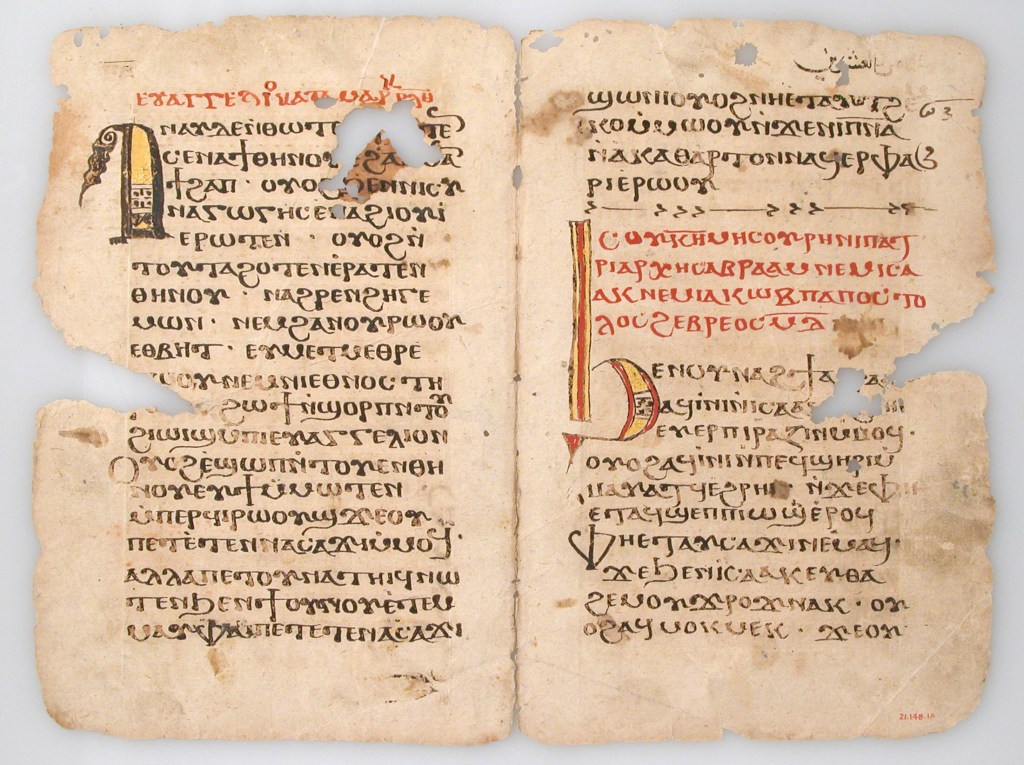

True, the tongues of Egypt would have still included Egyptian, specifically the final stage of the language known as Coptic. The corpus of Coptic literature demonstrates that Greek failed to replace native Egyptian speech entirely. Yet even in this regard, the power of Greek can be felt, because Coptic eschewed Egyptian writing systems and was written with Greek letters instead.

Alexandria remains a shining sun in the history of the Greek language. I would now have you recall, for this article’s purposes, that Alexandria is not in Europe.

Yet again, Alexander the Great was not the first person to bring Greek to the land in question; ancient graffiti carved into a colossal leg outside the temple of Abu Simbel attest to Greeks employed in Egypt as early as 591 BC. Nonetheless, in founding Alexandria, he left the legacy of a Hellenised and Hellenophone Lower Egypt. Alexander would be proud of this legacy. I’d wager he also would be greatly surprised by the teachings and the success of the religious movement that would later become synonymous with Greek speech and identity.

Christianity found a base in Alexandria. Tradition says that Mark the Evangelist was its first bishop. His status as an evangelist means that he has historically been identified as a writer of one of the gospels – surely the four most influential Greek texts of all time. I won’t venture an opinion on where the gospels were composed, but their subject matter (the life of Jesus of Nazareth) and context (Jewish and Greek culture in Roman Palestine) certainly do not point to their penning in Europe.

St. Mark was martyred and laid to rest in the city until that rest was disturbed by Venice’s ‘acquisition’ of his holy remains. As the legalised faith later established its structures and empire-wide hierarchy, Alexandria was one of the five top jurisdictions, officially all equal with each other, in an arrangement known as the Pentarchy.

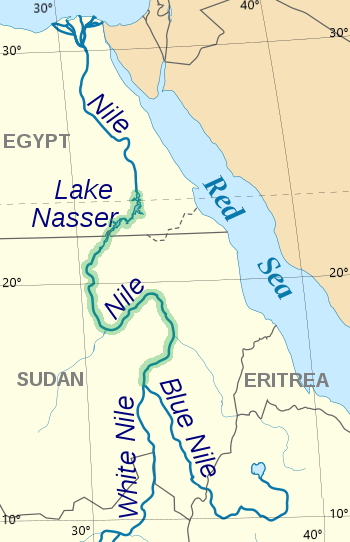

This set the city up as a religious centre with its own orbit; believers up and down the banks of the long Nile looked to the Patriarch of Alexandria for guidance and judgement. Much of that guiding and judging happened in the medium of the Greek language. Through this, Greek would thrive in regions to the south – even further south than the vandalism at Abu Simbel.

The Egyptians didn’t have exclusive ownership of the Nile. In the south, before the river splits into White and Blue, lies the historical region of Nubia. Today, it straddles the countries of Egypt and Sudan. In Nubia, the ancient Kingdom of Kush jostled for position with its neighbours: Egypt to the north, and later Aksum to the south and east too.

Egypt was an ancient frenemy for the Kushites. Shared culture between them has meant that it is Sudan, not Egypt, that today boasts the most ancient pyramids of any country.

Later on, after Alexander had been and gone, Nubia was in contact with Ptolemaic Egypt. This experience could be positive and negative; religion and art, as well as spears and arrows, might be exchanged. Kush’s capital city, Meroë, was greatly Hellenised under Egyptian influence, gaining essential Greek things like public baths. The story survives of one king in Nubia, Ergamenes, who…

“… μετεσχηκὼς Ἑλληνικῆς ἀγωγῆς καὶ φιλοσοφήσας…”

‘… had partaken of Greek education and loved wisdom…’

(Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica 3.6)

Wisdom-loving Ergamenes then went on to do some rather awful things to the priests of Meroë. Instances of sacerdicide aside, the city became “a little Nubian Alexandria” through interactions with Egypt under the Ptolemies, according to the historian M. I. Rostovtzeff. The welcoming of all things Greek in ancient Nubia must also have included the language.

The considerable employment of Greek there, alongside other languages, is perhaps best demonstrated by the downfall of Kush. The kingdom was conquered in the mid-4th century AD by Aksum, and the gloating victors set up inscribed thrones and standing stones across their enlarged kingdom. To ensure Aksum’s subjects could understand their betters’ declarations, such texts are often multilingual. We would expect to see a language like Ge’ez, a historical and liturgical language of Ethiopia, but Greek appears on them too.

In fact, this was the conquest of one African kingdom with a strong Greek tradition, by another African kingdom with a strong Greek tradition. Our fragments of information about the earliest days of Aksum, which would in time transform into the long-lasting Ethiopian Empire, are transmitted to us in Greek. Zoscales, an otherwise unknown 1st-century Aksumite king, was reported to be both ambitious and knowledgeable in Greek. Over the following centuries, his successors minted coins with Hellenised names and titles. The existence of Sembrouthes in the 2nd century is only known from a single inscription, written in formulaic but decent Greek prose, which acknowledges him as Aksum’s ‘king of kings’ – “βασιλεὺς έκ βασιλεών”.

Back in Nubia, the use of Greek there was not just a passing fad confined to antiquity. It seems to have withstood the fall of Kush, and then the arrival of Islam in Africa. As late as 1372 AD, we have a Nubian bishop, Timothy, being consecrated in Alexandria and sent back to his flock with a patriarchal greeting in Greek. The greeting is added to official documents testifying to Timothy’s consecration, which were later buried with him.

The documents’ use of Arabic (the language of regional politics at the time) and of Coptic (the language of Egyptian Christianity) is unsurprising, but the inclusion of Greek is unexpected. That is, unless we presume that it was going to be understood back in Nubia, and that, in the words of Stanley M. Burstein, “Greek remained the official language of Nubian Christianity right to the end of its long and remarkable history”.

It seems that that end came at the turn of the 16th century. Another island of the Greek language (in writing, if not also in speech) was finally overcome by the forces of history. If we include the Abu Simbel graffiti, both in terms of chronology and geography, then we have evidence for a millennium of Greek along the southern stretch of the Nile.

To conclude, somehow

Having journeyed first to the Hindu Kush and then to the ruins of Nubian Kush (a strange coincidence), I’m reminded of an archaeologist’s maxim: “pots are not people”. This piece of wisdom is intended to remind scholars that archaeological finds are not securely linked to people and their identities. One type of pot can belong to diverse peoples, and one people can utilise many types of pot.

The same is true of languages. Language is bound up with identity, often contributing to it, and yet also able to separate itself and wriggle free from allegiance to a single nation. Greek is one example.

On arrival, the Greek language may have first reached Bactria and Nubia borne by self-professed Greeks – that is, people calling themselves something like Ἕλληνες (Héllēnes) – but alternatively, in those ancient days, a single identity that matched exactly with all speakers of Greek may not have seemed obvious or important. Smaller identities like Ionian and Macedonian might instead have been foremost in their minds. For the average Alexandrian, I imagine that the Greek language was just a fact of life, not a personality trait that took precedence over being a denizen of that great city. By the time that today’s single, primary Greek identity emerged, an identity that also overlaps with European-ness, the Greek language had already slipped the net, and been given to the world.

What the world beyond Europe did with Greek is worthy of our consideration, study, and even speculation. It may well have taken on distinct new hews as it met other languages in the mouths and minds of Bactrian, Indian, Egyptian and Nubian speakers. It may have given words and sounds to them, and accepted the same in return. Had more texts come down to us today, new dialectal differences might be perceptible, but we only have scraps and fragments.

Nonetheless, one point stands: Greek has been a linguistic ingredient of parts of Asia and Africa, as well as of Europe. The difference in its durability outside of Europe has partly been a matter of concentration; smaller groups are more easily assimilated into a linguistic majority. Like colours on an artist’s palette, a limited language is soon lost in the mixture, but its contribution is still there in the overall picture.

END.

Non-linked references:

- Benedetti, M. (2014). Greek and Indian languages. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics. 59–62. Leiden: Brill.

- Burstein, S. M. (2008). When Greek Was an African Language: The Role of Greek Culture in Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Journal of World History, 19(1), 41–61.

- Hatke, G. (2013). Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. NYU Press.

- Nikoloudis, S. (2008). Multiculturalism in the Mycenaean world. Anatolian Interfaces: Hittites, Greeks, and their Neighbors. 45–56. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Rostovtzeff, M. I. (1957). The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire. Second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Stoneman, R. (2019). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press.

Texts:

Original website post. Images taken from Wikimedia.

Cover image: the 20-stater coin of the Greco-Bactrian king Eucratides I, found in Bukhara, Uzbekistan, and now located in Paris. It’s claimed to be the heaviest gold coin minted in antiquity.

Hi Danny,

Very interesting as usual. I know you were focusing on Asia and Africa but it would be interesting to add also a pinch of Magna Grecia and grico and grecanico spoken in modern-day southern Italy! Languages can really be a rabbit hole…

All the best, Saul

LikeLiked by 1 person