Like an insufferable fin-de-siècle socialite, I’m writing this on my honeymoon, a three-stop holiday that naturally never once ventures outside the old borders of the Austrian Empire.¹ As any self-respecting new husband should, it’s giving me the time to reflect on the two dearest things in life: a beautiful wife, and language history. No other of the destinations has prompted more contemplation of the latter delight than the great city of Trieste.

This Adriatic jewel – worn by Romans, Lombards, Venetians, Austrians and even the Triestines themselves as a short-lived independent country – is an impressive and charming place. Its grand streets shelter a happy hum of activity, especially on a warm summer evening, and it’s spoken of very positively by the loyal locals. Affection for “the city” unites the wider district, divided ethno-linguistically between Italian and Slovene.

Trieste has inspired great art over the centuries, having harboured names as great as James Joyce. Since I can never get my own prose to the level of a Joyce or a Stendhal, I will limit myself to some etymological reflections provoked by Trieste, specifically its name. These concern the inevitable messiness of mapping languages of the past, and the faint signal that those old languages may transmit to us in the present day.

To the Romans, Trieste was Tergeste/Tergestum. The city’s classical history is not hard to find; the tourist board boasts sights like the Arco di Riccardo and a Roman theatre. The second of those two, I was delighted to learn, was only excavated from beneath medieval sediment after a local scholar correctly recognised that the district of Rena was an abbreviation of arena.

“… ac superiōre aestāte Tergestīnīs acciderat…”

‘… and had happened to the men of Tergeste the summer before…’

Julius Caesar, Gallic War 8.24

However, the history of Trieste does not begin with the Romans. The city predated them, and had long existed when it was (re)founded as a Roman colony in the 40s BC. The name Tergeste is also not of Latin origin, being a place situated far to the north of that language’s homeland. Instead, it comes from the speech of the site’s pre-Roman inhabitants.

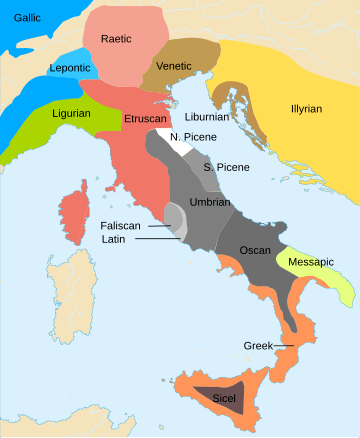

The linguistic origin is often identified by experts as Venetic, the language of the Veneti people, for which we have a small corpus of short surviving sources. This limited pool of text is enough for us to identify Venetic as some flavour of Indo-European. This is also the case with Illyrian, also once spoken in that region.

The exact relationship of Venetic and Illyrian to the rest of the family tree (and to better-known members like Latin, Sanskrit and Ancient Greek) is unclear.

We have a good idea of what the name of Trieste originally referred to: a market. The San Giusto hill that forms the nucleus of Trieste apparently not only offered a stronghold against attackers, but also a hub for trade.

But how can we know this, when we have so little evidence for Venetic and its vocabulary, and indeed for the Veneti-Trieste connection? The evidence in favour of deriving Trieste from an ancient local word for ‘market’ comes from a motley crew of current and historical words and place-names.

The key thing to note is that the ‘terg-‘ bit of Tergeste crops up elsewhere in Europe. Not far from Trieste, it appears in the ancient name for the city of Oderzo: Opitergium. This was also Venetic territory, and the repeat appearance of terg– could be taken as evidence that it was a common noun in their language, a term that might define more than one site.

Further afield, terg– is behind the name of the Spanish village of Tierga, west of Zaragoza. Appearances of terg– in Spanish place-names and archaeological sources cautiously support the claim that it was a word (or rather, word root) in the Celtic branch of Indo-European, which was present in ancient Iberia.

Yet these breadcrumbs of toponymy don’t tell us what terg– actually meant in the ancient tongues of southern Europe. One grave and one language family help with this issue.

The grave was that of Publius Domatius, whose tombstone was found in what is now eastern Austria, close to the border with Hungary and the city of Sopron. To the Romans, the region was Pannonia.

The tombstone’s inscription bears the description “TERGITIO / NEGOTIATOR”.

If this is the correct reading (the G of tergitio is a bit unclear), then it looks like we have another instance of terg-.

This time it appears in an unfamiliar job title. This is likely a local word pushed into a Latin-writing context, and it helpfully comes with a Latin translation: negotiator ‘merchant, businessman’. It seems that the people who set up this epitaph for Publius didn’t think that calling his profession tergitio was clear or proper enough for the formal language of a tombstone. Lucky for us, they then immediately rendered it with a standard term.

Publius was engaged in negotium, being a man who worked and traded for a living – he was not (nec) a man of leisure (otium). In their society, though, tergitio or the underlying word in the local language was the primary title for such a person. We can presume that the terg– bit was the root of the word, and referred to where you would find a tergitio like Publius (at a market) or what you would find him doing (business).

On the basis of place-names like Tergeste, we have enough evidence to claim that an element like terg- existed in hard-to-pin-down historical languages around the western Mediterranean. The grave of Publius then offers evidence to presume what it meant. This etymology then gets a boost from another language family.

Travelling north of Trieste and Sopron, the other major source of evidence for the meaning of terg– comes from the Slavic languages, specifically their common ancestor, Proto-Slavic. If you know a Slavic language, the supposed meaning of terg– as ‘market’ may have felt obvious. For example, in Polish, a market is a targ. In Russian, торг (torg) means ‘haggling’ and ‘auction’. In Slovenian and Serbo-Croatian, a trg is a town square or marketplace. In Czech and Slovak, with their characteristic H instead of G, a trh is again a market.

On the basis of this Slavic spread, we can reconstruct a common ancestor word in the lexicon of Proto-Slavic. This prehistoric word for ‘market’ was *tъrgъ. It can be reasonably understood to be a sister or cousin of terg- in the historical languages to the south, and therefore to support their ‘market’-etymologies.

This root word not only sprouted into a tree of Slavic cognates and derived words (e.g. Serbo-Croatian tržnica ‘marketplace’); it also passed into other, non-Slavic languages. In Sweden and Norway, you can find it as an ordinary town square (torg). Slavic markets connect the Finnish city of Turku to the Romanian city of Târgoviște.

The Slavic words and that Pannonian grave offer good evidence for the meaning of the terg- root behind the name of Trieste. What is less clear is how this root ended up in the respective languages. The Mediterranean words give us little indication of their prehistory, while the pre-Slavic origin of *tъrgъ is much debated. If we want to claim that all these instances of terg- are in a historical sense the ‘same’ linguistic object, strewn across different European languages, this prompts the question of its journey to those different destinations.

When similar-sounding and similar-meaning words pop up in different languages, the etymologist has three ways to explain it: coincidence, inheritance, or borrowing.

I think we can dismiss the first option in this case. The Slavic and Mediterranean words look similar enough to be cognates, and Publius’ profession is a match in meaning with the Slavic. This is to say, I think there is a common origin at work here, although others do disagree; some Slavicist scholars claim that Proto-Slavic *tъrgъ is unrelated to the rest.

Could it then be inheritance? That is, could terg- be an ancient root maintained by all of these Indo-European languages from their common ancestor? It is possible, and I have seen it claimed by experts. One, for instance, writes that an ancient root like *terg- “can be projected back to a stage before the emergence of the individual branches of Western Indo-European” (Stifter 2022: 133). Through such serious antiquity, it could then end up in languages as diverse as Proto-Slavic and the ‘Maybe Venetic’ language of pre-Roman Trieste.

For myself, I remain unconvinced by this. To make the case for a common prehistoric ancestor convincingly, we etymologists need a wide set of cognate words, wide enough for shared inheritance to become the most reasonable explanation. Instead, all we have here is a suite of Slavic words, a grave from Pannonia, a handful of old place-names, and maybe also the Albanian word treg (‘market’).

Compared with the evidence for securely Indo-European headline words like mother, father, brother and sister, it’s not much to go off for claiming that terg- belongs to a very early stage of Indo-European development. We also don’t find it at all in other western branches of Indo-European, like Italic and Germanic, and the evidence for its presence in Celtic is meagre. In short, to call terg- an ancient Indo-European root more confidently, we need more Indo-European evidence for it.

What about borrowing? That is, the passing of the word laterally, from language to language? Again, it’s possible. Some scholars have suggested that the origins of terg- lie far away, in the ancient languages of Mesopotamia. Others have proposed that it is European in origin, but specifically pre-Indo-European – that is, adopted from a language that was present in South Europe before the arrival of Indo-European speech (see: Paliga 2015).

From that southern location, it might then spread northwards, being passed on until it reached the Polesian homeland of Slavic. Who exactly passed it on to the early Slavs and what their language was, would be two further gaps for the story to fill. A journey from the south seems more plausible, what with the Mediterranean being a hub of mercantile activity, but the opposite direction and an ancient northern origin for terg- and ultimately Trieste can’t be instantly ruled out.

Coincidence, inheritance or borrowing? I won’t attempt to resolve this scholarly debate over the origins of the different instances of terg-, nor suggest an alternative view. I don’t feel up to that task. What I find myself reflecting on instead is the messiness of etymology and language history. It is to be expected that some puzzles set by the linguistic evidence simply don’t have a neat solution.

Writers of the past wrote according to everyday purposes; they did not set out, with future etymologists in mind, to present the entirety of their language in an accessible format. It’s a shame they didn’t, but we can’t blame them. Whether or not we have surviving evidence for an individual’s language also depends on who that person was, the culture of writing they may have been a part of, the durability of the materials they wrote on, their social status and ‘worthiness’ in the opinion of later people preserving their words.

Consequently, our historical evidence for languages of the past is like a frayed and feeble net, managing to catch some aspects of bygone language, but letting a great deal fall freely into oblivion.

The somber fact remains that the vast majority of human linguistic output is, by now, silence. It gets lost to time, either immediately or not long after it was first produced. We remember and record only a fraction of the speech, scribbles, signs and grunts of people living today; whole human lives of the past, perhaps the majority of them, have left us not a whisper.

The business of etymology and historical linguistics reflects that. For every person, word or language that we today have an abundance of linguistic evidence for, there is a person, word or language that is just teetering on the edge of our ignorance. The case of Trieste strikes me as an example of the latter: a pitiful constellation of small lights, glimpsed through a glass darkly.

Often, in the study of the Indo-European family, we deal with securely related words across languages (e.g. English father = Latin pater = Sanskrit pitā́) that we can project back into a shared prehistory. Sometimes, though, history has left us with a Trieste situation: a paltry sum of place-names (Tergeste, Opitergium), isolated items (tergitio) and family-specific words (Proto-Slavic *tъrgъ). We have so few pieces of the jigsaw puzzle here to guess the complete picture from. How these lexical leftovers fit together is a head-scratcher with no obvious resolution.

Was the terg- behind Trieste an ancient root meaning ‘market’ that formed part of the Venetic language’s Indo-European heritage? Or was it a wandering word with far-away origins, stopping off in Venetic on its journey to various European destinations? To both ideas, my personal answer remains “it’s possible, but I’m not convinced” – whatever that statement actually means, the ideas just don’t pass the internal psychological thresholds of ‘I think that…‘ or ‘I believe that…‘. They linger instead in the limbo of possibilities, hoping for future finds or subsequent scholars that will rescue one of them and elevate it to the realm of belief.

So, that’s what I’ve been thinking about on my honeymoon.

END.

Footnotes

- I’d put Austro-Hungary, but the honeymoon included a day’s adventure into the historical region of Friuli, which I believe was added to Italy in 1866, while the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary was created in 1867. As I say, insufferable.

References

- Chang, W., Cathcart, C., Hall, D., & Garrett, A. (2015). Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis. Language, 91(1), 194–244.

- Gluhak, A. (1993). ‘tъrgъ’. Hrvatski etimološki rječnik. Zagreb: August Cesarec. 637.

- Paliga, S. (2015). Slavic *tъrgъ, Old Church Slavonic trъgъ. Their origin and distribution in postclassical times. Slavia Meridionalis, 15. 42–52.

- Stifter, D. (2022). Contributions to Celtiberian Etymology III. The Bronze of Novallas (Z. 02.01). Palaeohispanica: Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania Antigua, 22. 131–136.

- 455 Grabstele des Publius Domatius

From DEX

Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române

tîrg (-guri), s. n.1. Loc întins într-o localitate unde se vînd vite, cereale, lemne etc., obor.2. Contract, afacere încheiată.3. Piață, hală.4. Oraș, orășel.5. Tranzacție, vînzare-cumpărare.6. Învoială, înțelegere, discuție, sume date și primite. Sl. trŭgŭ (Miklosich, Slaw. Elem., 49; Cihac, II, 401; Conev77), cf. rus. torg “obor”, alb. treg.

Legătura cu un preromanic ◊terg (Lozovan, ZRPh., LXXXIII, 128 și134) este posibilă, dar nu pare suficient documentată. Prima organizare administrativă a tîrgurilor este cea a lui Alexandru Lăpușneanu, în1561.

Der. tîrgar, s. m. (înv., zaraf, bancher; Trans., cumpărător, client); tîrgoveț, s. m. (orășean, locuitor al orașului), din sl. trŭgovĭcĭ; tîrgoveață, s. f. (orășeancă); tîrgoveți, vb. refl. (a se face orășean); tîrgui, vb. (a cumpăra; refl., a se tocmi, a discuta prețul; înv., a cădea la învoială), din sl. trŭgovati; tîrguială, s. f. (învoială; cumpărătură). De aici și Tîrgoviște, numele unui oraș, vechea capitală a Munteniei, cf. bg. tèrgovište, și expresia gură de Tîrgoviște “gură-rea”, pe care Weigand, Jb., XVI, 76, o interpretează greșit pornind de la înțelesul Tîrgoviște “tîrg în general”, cf. Tiktin; e sigur că acest cuvînt se folosea înainte ca nume comun, dar la fel de clar este că expresia se datorează reputației de care se bucurau femeile din orașul cu același nume.[DER]

LikeLike

Very interesting! You seem to enjoy your honeymoon, dear Danny. I was just wondering if there could be a relation to Scandinavian torg (as in Swedish for Marketplace)?

LikeLiked by 1 person