Freshly disembarked from lagoon-voyaging vaporettos, I now find myself left with only fond memories of two recent days in Venice and on its nearby islands.

Venice is a city to which the description of ‘unique’ at last seems fair, and somewhere that is easy to become obsessed with. Its amphibious lifestyle, where waves, not pavements, await at door thresholds, feels almost like a deliberate rejection of the norms of the modern world. Its compact, clustered geography contrasts with its global impact on world history.

A part of that impact is linguistic, as Venice and its vast trade networks were either the source or the conduit for words in countless modern European languages. These certainly include English. Aside from some obvious, Venetian-vibed terms (such as gondola), many of Venice’s contributions to the English lexicon are very ordinary words, without a whiff of Adriatic air.

So, this post is my linguistic tribute to Venice, in particular to what it has given English. To be featured in this selection, the everyday English word must have somehow originated in, passed through or been inspired by the Venetian language on its journey to us today.

“The Venetian language?” you may wonder. Yes indeed – Venice and the Veneto region have for centuries had their own distinct variety of language, descended from Latin. ‘Dialect’ is an alternative term, but this risks subordinating Venetian to another language, namely Italian.

What we call Italian has a geographical origin in the central region of Tuscany, more specifically in medieval Florence. Italian-to-be was once “a mere face in the crowd”¹, and the future accolade of Italy’s standard language was still up for grabs. If history had turned out differently, it might have been Venetian that became Italian.

The Venetian language is also recognisably different to Italian. You can compare the two through their respective treatments of the Latin word ducem ‘leader’. In Tuscany and therefore in Italian, this became duce, a word with twentieth-century fascist associations. In the Veneto, this became the distinctly Venetian title of doge.

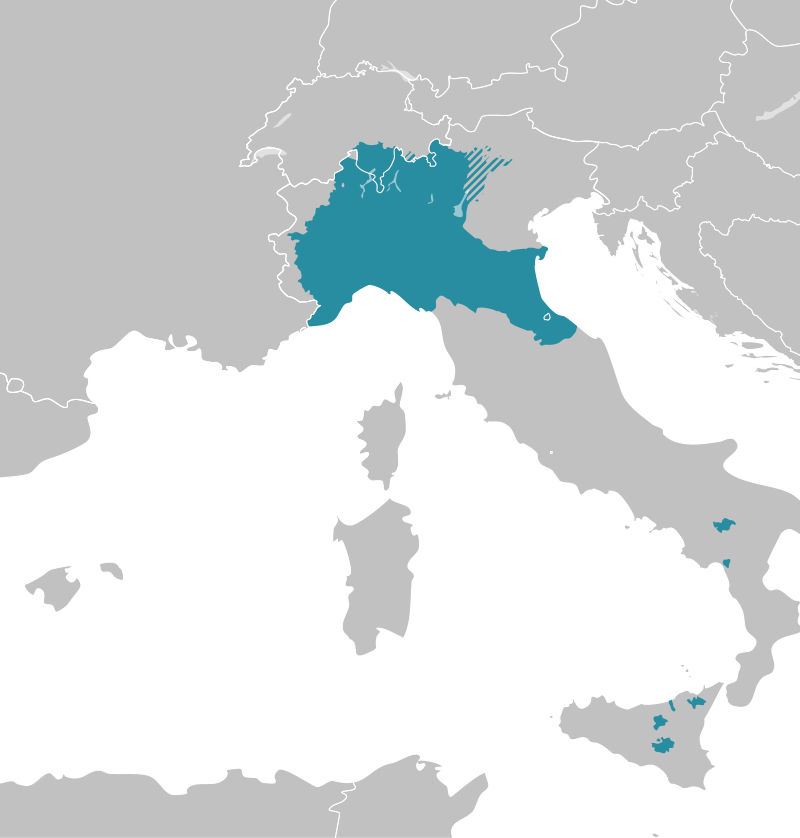

Like other north-Italian dialecto-languages, Venetian also does not share Italian’s love for double consonants. While Italian has vecchio ‘old’ and sotto ‘under’, Venetian has vecio and soto. The classic Venetian bar nibbles, cicheti, are cicchetti in Italian.

As well as in sound, there are differences too in vocabulary. Even the briefest stroll through Venice will reveal Venetian’s penchant for calling an alley a calle, whereas Italian prefers via or vicolo.

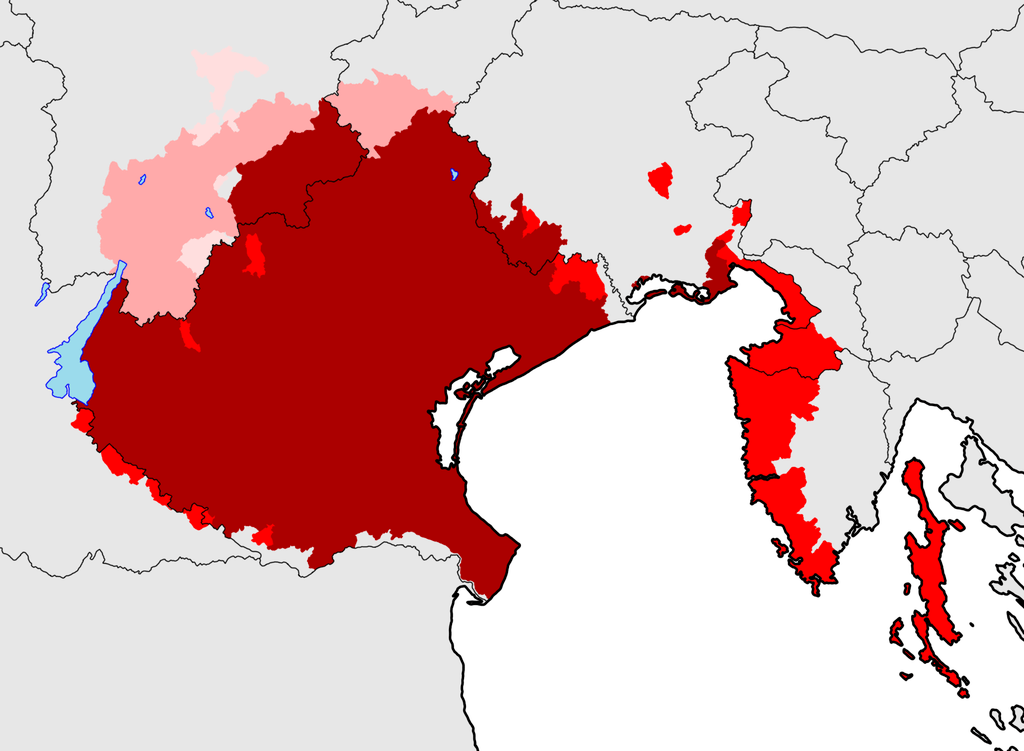

What I find most interesting is that the genealogy of Venetian is a much-debated, apparently still-undecided matter. Its Latin ancestry is unquestioned; the problem is how it fits into the Romance family tree that sprouted from Latin. Its branch is identified on the basis of similarities in sounds, words and grammar between Venetian and other Romance languages. Some scholars and resources (like Glottolog, which lists its current status as “threatened”) place Venetian within the Gallo-Italian branch, alongside Ligurian, Lombard, Emilian and other languages of northern Italy.

Others situate it instead among the Italo-Dalmatian languages, which would make Venetian a sister of Standard Italian. Venetian continues to challenge our understanding of Romance in general, but we know enough about the language, its speakers and its history to identify Venetian’s legacy in English words.

Having sifted through etymological dictionaries and resources for traces of Venetian, here are twelve everyday words which previously passed through the canals of the Serenissima on their way to English.

ghetto

To begin, we have the concept of a ghetto, all instances of which trace their history back to the original ghetto for the Jewish population of Venice. Jews in Venice were confined to the Cannaregio district of the city by its government in 1516. The term ghetto emerged from this act, although its earlier meaning is disputed. A leading theory is that it was simply the Venetian word for ‘foundry’ (gheto) that led to the term, the area being a centre of metalworking.

orange

Located at the heart of a network of trade routes, Venice was the doorway to Europe for many goods and words from Asia and Africa. It may have been first through Venice that orange entered European languages, having originated far to the east, in a Dravidian language of India, and passed through Persian and Arabic. It appears in Venetian as naranza, beginning with an N that’s lost from English’s word. This is one example of ‘rebracketing‘, whereby Italian or French speakers started treating the initial N as belonging to a preceding indefinite article. That is, a phrase like un’ narancio ‘an orange (tree)’ turned into un arancio in Italian, and one of the new N-less forms of the fruit made its way north into English.

artichoke

Orange is not alone; among the many gastronomical terms that Venetian has served Europe, there is also the artichoke. This plant and vegetable grow well in the Venice area, where you can find highly prized violet artichokes growing on the island of Sant’Erasmo. It appears first in Venetian sources from the sixteenth century, and it looks like a borrowing and remodelling of Arabic خرشوف (ḵuršūf), with the Arabic definite article al- added on too. The Arabic word has provided Italy with two words for the artichoke: articiocco in the north, and carciofo elsewhere.

zany

Zany, meaning ‘amusingly eccentric’, goes back to an ordinary personal name. It’s Venice’s equivalent of Johnny – Zani is the Venetian version of Italian Gianni, diminutive of Giovanni. Its association with wackiness is thanks to Commedia dell’arte, the popular genre of Renaissance theatre. Among its original stock characters is the Zanni, the crafty and funny servant.

pants

Commedia dell’arte again makes a contribution to the English lexicon, this time in the form of the word pants. This word has a history full of twists and lexical leaps. It comes immediately from a clipping of pantaloons, a garment that got its name from the character in the genre that wears the full-leg trousers: Pantalone. This is the greedy old man in Commedia dell’arte, the successful merchant who speaks with a Venetian accent. Shakespeare references the character in his famous All the world’s a stage speech:

“… The sixth age shifts

As You Like It 2:7

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank…”

The name Pantalone is likewise Venetian-inspired, taken directly from either Saint Pantaleon, a popular saint in Venice, or from the many Venetians named after the saint. The saint’s name in turn is of Greek origin, a compound word literally meaning ‘all-merciful’.

gazette

A gazette is today a word for a newspaper or journal, so you might be surprised to learn that it was originally a Venetian coin. A gazeta was a low-value coin issued and used in Venice from the sixteenth century. With one gazeta, you could pay for a copy or a loan of a simple news-sheet. This common practice for a cheap price meant that the newspaper itself came to be called a gazeta, and the name has stuck.

sequin

As well as the gazeta, Venice’s mints provided our numismatic lexicon with the ducat (the ‘duke’s/doge’s’ coin) and the zecchino. The latter is a gold coin, produced in Venice from the thirteenth century. It’s zechin in Venetian, derived from Arabic سكة (sikka), a word for ‘mint, coin’. With such small and shiny circular disks, it’s not too striking that zechin is behind sequin.

lagoon

Venice and its nearby islands situate themselves in the famous Venetian Lagoon, the bay that offered protection to people fleeing the mainland during the upheaval of the Western Roman Empire’s final decades. The word lagoon clearly has a Latin origin (lacūna), but it may have been specifically the Venetian Lagoon and/or the Venetian word for it that are responsible for the common noun today. Most sources will rightly say that lagoon comes from Italy, but early appearances of it relate to Venice. What’s more, its voiced /g/ sound is typical of northern Italian languages, including Venetian, rather than the Tuscany-based standard.

contraband

Being a maritime and mercantile might, Venice was naturally very concerned about smuggling and illegal dealing. Goods that were against regulation (in Medieval Latin: contra bannum) were contrabando in Italy, and it looks like it was the Venetians who first coined this term, with “contrabannum” first occurring in Latin writing from the area in the thirteenth century.

ballot

In terms of etymology, a ballot is straightforwardly a small ball. A “balota” is mentioned in the thirteenth century again in the context of Venice, where these small balls were used to cast votes in elections. These included the election that selected a new doge. Since the position of doge was for life, the men elected were usually elderly, to ensure that their term of office didn’t go on too long. Venetian elections were complicated and fraught with political danger, so counting up small balls provided some anonymity.

arsenal

If you head to the east of Venice, you’ll meet the impressive gates of the Venetian Arsenal, the old area of armories and dockyards. Measuring 110 acres and once employing thousands of workers, the scale of the arsenal’s operation is truly impressive. It provided Venice with the ships and technology that made it an international superpower. It gave its name to other dockyards and stores of weaponry, including London’s Royal Arsenal. But where did Venice get the word from? From Arabic again, specifically دار الصناعة (dār al-ṣināʿa) ‘factory’, literally ‘house of manufacture’.

quarantine

Lastly, a word that became all too topical in 2020. This forced period of seclusion has a number behind it: forty. This is the number of days that the Venetians might make a ship and its passengers wait in isolation, to halt the spread of diseases from abroad. Venetian quarentena is documented from the fourteenth century, the same century as when the infamous Black Death hit Europe.

So, this is my selection of English words with the most serene etymology. There are certainly more that could be mentioned, so great is Venetian’s linguistic influence.

To end, I’ll leave you with an originally Venetian valediction. Coming ultimately from a term for ‘Slav’, the word Sclavus came to mean ‘slave’ in general in Late Latin/Early Romance. The Venetians then used sciavo in obsequious farewell phrases meaning ‘I am your slave’ or similar. This was abbreviated, leaving only a short and popular way to say goodbye:

Ciao!

END

References

- Maiden, M. (2002). The definition of multilingualism in historical perspective. Multilingualism in Italy: Past and Present. 31–46. Legenda.

Resources

- Benincà, P., Parry, M., & Pescarini, D. (2016). The dialects of northern Italy. The Oxford guide to the Romance languages. 185–205. Oxford University Press.

- Ferguson, R. (2013). Venetian language. A Companion to Venetian History, 1400-1797. 929–957. Brill.

- OED.

- Vocabolario storico-etimologico del veneziano

Pictures my own or taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Great article! Now, how about a follow up article on the Italo-Dalmatian languages?

My grandparents, being Calabrian, spoke the Calabrese and Sicilian dialects, which are incomprehensible to me after having studied Standard Italian. Also, why the Dalmatian connection? Is there a relationship to Croatia?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! You ask a great question, one I wonder about too. It’s true that there was once such a thing as Dalmatian, a Romance language spoken along the coast of what’s now Croatia. However, it died out over a century ago, and the few sources we have show a language with influences from Venetian. Hence, I’m not sure on what basis scholars group it with Italian languages, other than geography!

LikeLike

Dear Danny,

what a lovely text. Thank you.

It clearly shows not only your passion for languages but also your deep admiration for Venice.

I share both.

I am going to send you an invitation to a webinar which I receved almost simultaneusly.

It is in Czech but the topic might be interesting for you.

The mysterious Etruscan language as being a Slavonic. Two historical attempts to prove it 🙂

Vladimir

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sequin and zany are big surprises for me (the latter seems as English as zounds). Orange (< naranga) is such a wanderlust ridden word. One of the ones I mentioned in my piece on Sanskrit vocab that has made into English.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article! I’ve visited Italy several times, but only Tuscany and Rome, so as far as I can say I’m familiar with Italian, it’s only the official version (although I’m aware there is a lot of regional variation).

The distinction between “duce” and “doge” seems obvious. When you distinguish between Italian “vecchio and sotto” and Venetian “vecio and soto“, though, is there a difference in pronunciation or just spelling?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for this kind comment! To answer your question: yes, the relative lack of double consonants is a feature of speech too. In Italy south of the so-called ‘La Spezia–Rimini’ line, double consonants (geminates) are very common, even more so than writing might reflect. Above the line, including in Veneto, they have typically been reduced to single sounds, as they have been in Spanish, French, Catalan and Portuguese.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the clarification!

LikeLiked by 1 person

gorgeous pic👌

LikeLike